Music and ceremony in Maximilian's Innsbruck

The Innsbruck Landtag of 1490

In the first week of March 1490, Maximilian I, King of the Romans, arrived in Innsbruck for the political congress that would decide the future of the Upper Austrian lands that belonged to his cousin, the ageing Archduke Sigmund.[1] Sigmund’s reign over his territories in the Tyrol and Vorlande had been of great concern to the King, Emperor Friedrich III and the local Estates. The Archduke was an irresponsible and frivolous ruler who had been wasteful of the income he received from the region and now threatened to sell most of his lands to the Duke of Bavaria – an unpopular plan opposed by Maximilian and Friedrich, who wished to keep the territories in Habsburg hands. At the start of March 1490, Maximilian travelled to Innsbruck to resolve this matter once and for all, arriving in the town with an impressive entourage that included many princes of the Empire.[2]

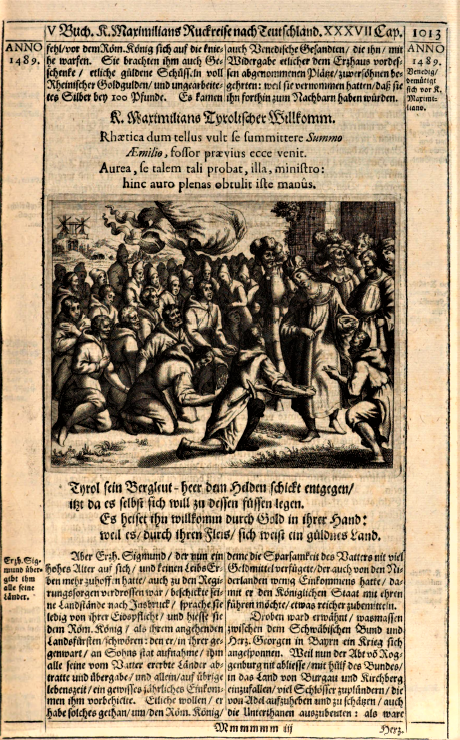

In 1668, the Nuremberg poet Sigmund von Birken published a historical work on the Habsburg rulers, » Spiegel der Ehren des höchstlöblichen Kayser- und Königlichen Erzhauses Oesterreich (Nuremberg, Endter: 1668), which reports on Maximilian’s Innsbruck visit. If we are to believe Birken’s account, Archduke Sigmund “received [Maximilian] magnificently, and amongst other diversions, led him to see the treasures of the Tyrol”.[3] The “treasures” were the silver mines that promised the province and its Archduke great prosperity and counted amongst the Habsburgs’ most valuable possessions at that time. [4] Their importance to the region and to the Archduke is represented by Birken in an image that depicts Maximilian’s visit (» Abb. Maximilian I is received by Archduke Sigmund). Here, the King is shown greeted by the miners of the region, described by Birken as “7400 in number, [who] came towards [Maximilian and Sigmund], under a billowing flag, in good order, and upon the Archduke’s command, fell to their knees before the Roman King.”[5] A number of gifts were then presented to Maximilian – “several golden dishes full of Rhenish guilders and 100 pounds of unworked silver” – as were Venetian envoys, who wished to reconcile themselves with the king who was likely to inherit Sigmund’s lands.[6] The significance of this meeting is further celebrated by Birken in two epigrams entitled “King Maximilian’s Welcome to the Tyrol”, the first in Latin, the second in German. While similar in their message, the two epigrams differ in some respects. In the first one, the Tyrol is given its Latin name “R(h)aetia” while Maximilian is named “Greatest Æmilius”:

Since the Rhaetic land wishes to offer obedience to the Greatest Aemilius,

Behold, a miner comes to meet him.

That golden [land] proves herself golden by means of a golden servant;

Hence he [the servant] has offered hands full of gold.[7]The German epigram again refers to the wealth of the Tyrol and the work of its miners, this time identifying Maximilian as “the hero”:

The Tyrol sends its troop of miners towards the hero,

Since [the province] itself now wishes to fall at his feet.

He is welcomed by gold in their hands:

As through their hard work, it has proved to be a golden land.[8]This retrospective account presents Maximilian already as the hero of the Tyrol as chosen by Archduke Sigmund. Following the two epigrams, Birken recounts that Sigmund had convened the Landtag from 8 March to have his Estates swear their allegiance to Maximilian as the new Archduke.[9] Yet, the proceedings of the Landtag were not so clear-cut. Only after the Tyrolean Estates had expressed their grievances against Sigmund’s poor government of his court and lands, did Maximilian manage to privately persuade the Archduke to abdicate, promising him a large subsidy as well unrestricted hunting and fishing rights in the Tyrol. As a result of this agreement, which was formally communicated to the Tyrolian assembly on 16 March 1490, Sigmund relinquished his rule over the Tyrol and the Vorlande to Maximilian.[10]

Innsbruck as Residenzstadt

Innsbruck had been the seat of the Tyrolean government since 1420, when Sigmund’s father Friedrich IV of Austria, nicknamed “mit der leeren Tasche” (Frederick with the empty purse) had moved his residence to the town, constructing the palace that would remain central to the administration of ducal power for years to come. The court and palace grew in size as the dukes gained in wealth, this expansion being characteristic of the reign of Sigmund, which commenced in 1446. His income from the region’s salt and silver mines and its trade with southern Germany and Italy enabled him to develop a court of great cultural and intellectual significance, the extravagant festivities of which shaped life within his palace and the surrounding area. Sigmund, a popular figure, often participated in the celebrations of his subjects in Innsbruck or the nearby town of Hall.[11] (» D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck; » D. The Waldauf foundation.)

In the years after 1490 Maximilian developed a particular fondness for the Tyrol, which appealed to the young king on several counts: its location on the Brenner Pass meant that it was an ideal stopping point for those travelling between Italy and northern Europe; the nearby silver, copper and salt mines continued to provide a steady source of income; and the region provided the ideal surroundings for his favourite pastime of hunting (» Abb. Hunting and fishing).

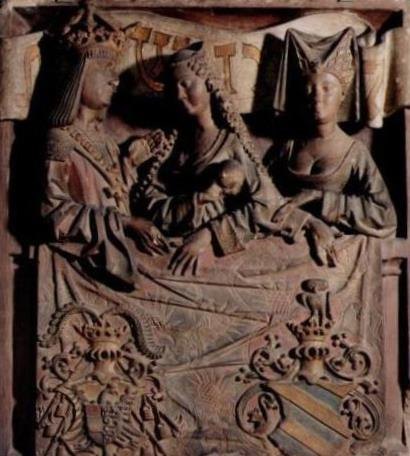

Despite the king’s frequent and prolonged absences from Innsbruck, the town was not entirely without a court presence under Maximilian. While many of those employed by the royal court accompanied the monarch on his travels, other officials were permanently resident in Innsbruck, which played a crucial role as an administrative centre. And like Sigmund, Maximilian established his own residence there, in the palace which he likewise renovated and extended; the famous golden roof of the king’s treasury (added years later) is a lasting mark of Maximilian’s influence in this respect (» Abb. The Innsbruck palace with its golden roof). Yet Maximilian’s adoption of the Innsbruck palace as his main (though not permanent) residence did not mean that Sigmund was fully to relinquish his former home. Until his death in 1496, he and his wife Katharina of Saxony were to live in the “Neuhof” – the part of the palace that had been built by his father Friedrich back in 1420 – while Maximilian took up residence in the newer “Mitterhof” when visiting the region.[12]

Music traditions of the Innsbruck court

By inheriting Sigmund’s Innsbruck palace, Maximilian acquired a residence that had a rich history of music-making. Due to the former Archduke’s generous income from the province, he had been able to sustain a cohort of musicians that comprised a trumpeters’ corps whose numbers varied between three and ten, a wind band of around four members (shawms and slide brass instrument) as well as individual lutenists, harpists and a court organist (» D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck; » G. Nicolaus Krombsdorfer; » K. Leopold-Codex). It was these musicians that had been drawn on for Sigmund’s wedding to Katharina of Saxony in February 1484, which, according to those in attendance, brought together all of Germany’s nobility in a celebration that lasted for more than eight days. The pilgrim Felix Faber wrote in his diary (1484): “Having entered into this town, we found it full of noblefolk and armed men. Princes, counts and barons had come to visit the archduke, because at this moment the souverain celebrated his wedding to the daughter of the Duke of Saxony: it was for this reason that the nobility of all Germany had assembled here.”[13] The Hofmarschall was instructed to ready the trumpeters, pipers and singers (presumably of St Jacob’s) who would participate in various elements of the festivities, including the procession to the church, the wedding banquet, joust and dance. As Johann Nohen von Hirschfeldt noted, „daselbst ward Hof gehalten mit aller Köstligkeit acht tag und lenger, mit rennen und stechen, dantzen und springen“.[14] While Sigmund’s dwindling finances resulted in a decline in his musical patronage by the end of his rule, the core of his musical establishment endured: six trumpeters, a trombonist and drummer all transferred their allegiance to Maximilian in 1490, as did the great court organist Paul Hofhaimer.[15]

Maximilian’s musicians

Upon the strong musical foundations provided by Sigmund, Maximilian was able to gradually amass a musical establishment to match his rising status in the Empire and Europe, [20] inheriting further musicians from the household of his father Emperor Friedrich III following his death in 1493, and recruiting additional members from cities and courts across his dominions.[21] Maximilian drew many of the best musicians in Europe into his service, some of whom are immortalised in the images of the Triumphzug.[22] There, for example, Anton Dornstetter is named master of a group of fifers and drummers and Hans Neuschel (» Abb. Triumphzug Bläser; » I. Kap. “Musica, schalmeyen, pusaunen”), the famous trombonist and brass instrument maker of Nuremberg, leads an ensemble of shawms, trombones and crumhorns . Paul Hofhaimer is then pictured playing a positive organ (» Abb. Triumphzug Regal) and in the final image devoted to the music of the court we see the members of the chapel choir along with the trombonist Hans Stewdl and the Augsburg cornettist Augustin Schubinger (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei; » I. Instrumentalkünstler). Yet, the complexities and challenges of Maximilian’s reign, as well as the nature of the court records that have survived, make it difficult to determine the exact number of musicians in his employ at a single time. Only the core musical personnel inherited from Sigmund appear regularly in the financial accounts of the Innsbruck court: in addition to Hofhaimer, merely the trumpeters, trombonists and drummers are recorded here whereas references to other instrumentalists are more sporadic. However, other sources confirm the greater range of musicians employed by the king. We know, from correspondence of the court, for example, that a chapel of nine members – comprising two bass singers and six choristers under the leadership their Singmeister – was moved from Augsburg to Vienna in 1498.[23] And civic accounts contain numerous payments to instrumentalists in Maximilian’s service, not documented in the Innsbruck records, such as the pair of lutenists paid by the civic council of Augsburg during the 1490s, which included the “Meister Artus” (Albrecht Morhanns) who was likewise celebrated in the Triumphzug (» Abb. Triumphzug Süße Melodie).[24]

Based on these additional court and civic sources, Keith Polk suggests that by 1500, in addition to his Kantorei, Maximilian had some 28 instrumentalists at his disposal: two lutenists, four “geiger”, a wind band of five members (three shawmists and two trombonists, who also doubled on instruments such as cornett and crumhorns), up to twelve trumpeters, a Swiss band (drummers/fifers) of two or three, as well as the all-important Hofhaimer.[25] Yet, how many of these individuals performed for Maximilian on a single occasion – including in Innsbruck – is unclear and presumably varied as the occasion required. Furthermore, in the early years of Maximilian’s reign, a number of the musicians he inherited from Sigmund continued to serve the old Archduke as well as the new king. These musicians might therefore have performed for either Archduke in Innsbruck, or with Maximilian on the road. Hofhaimer, for example, was described as being Sigmund’s organist in a letter from the Dukes of Saxony, Friedrich and Johann, in 1494, that is several years after he had officially moved into Maximilian’s employ.[26] While during Archduke Sigmund’s reign, the organist of the court seems to have also acted as organist of St Jacob’s, under the ever-itinerant Maximilian, Hofhaimer’s frequent absences in the king’s entourage meant that a new town organist was eventually appointed to meet the demands of the Innsbruck parish.[27]

Performances in Innsbruck

Payment lists and chronicles of the far-flung regions visited by Maximilian’s court reveal the great variety of entertainments in which his musicians participated: dances, banquets, jousts, processions, carnivals and church music all featured here. It was for the most important feast days and political events, that Maximilian seems to have reserved the greatest displays of courtly ostentation. The Church’s high feasts of Christmas, Easter, Whitsun and Corpus Christi were all marked by appropriate processions and services that often involved the singers and organist of the Hofkapelle; Christmas and New Year were celebrated with performances outdoors by the court’s trumpeters; and Shrovetide involved all kinds of mummeries and dancing, jousts and weddings.[28]

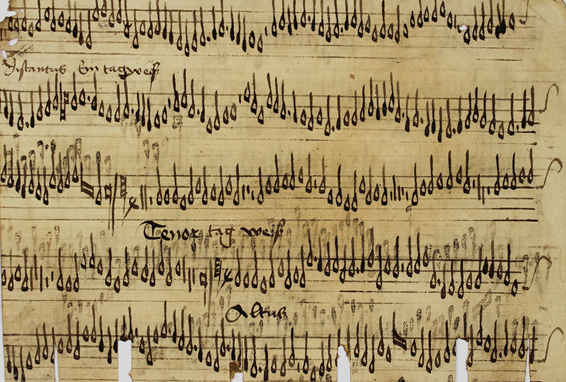

Unfortunately, records of the court provide only glimpses of such performances in Innsbruck. Yet there is evidence of the repertoire that may have been performed in the palace there. A set of fragments from a large collection of sacred and secular polyphonic music, found in the Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek Linz (» A-LIb Cod. 529), is datable ca. 1490–1492 and probably derives from musicians of the Habsburg musical establishment (» K. The codex of Magister Nicolaus Leopold; » C. Kap. Handschriftliche Quellen zur Missa Salve diva parens). The pieces – song settings, French chansons, liturgical music, ceremonial motets – are largely copied here without texts and in arrangements suitable for instrumental players. A typical piece is the otherwise unknown fragmentary four-voice setting of a German song entitled simply “ein tagweiss” (morning song, alba) (» Abb. Ein tagweiss).

While court records offer only limited descriptions of performances in Innsbruck, ambassadors who visited from various regions of Europe often included details of musical events in reports of their dealings with the king. It is these accounts that will be explored below, as valuable sources of information about performances in Maximilian’s Innsbruck.

The arrival of Bianca Maria Sforza

One occasion that gave rise to accounts of musical performances during the early years of Maximilian’s governance of the Tyrol, was the celebration of his marriage to Bianca Maria Sforza, daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, in spring 1494. The wedding had taken place by proxy in Milan on 30 November 1493, Maximilian represented by Margrave Christoph of Baden, and now, in Innsbruck, the newlyweds would celebrate together.[29] Bianca Maria had left Italy for Innsbruck on 5 December with a large entourage, including members of her family. After making various stops en route, she arrived in Imst on 20 December where she was met, not by Maximilian, who had been detained in Vienna, but by Sigmund and his wife Katharina. From Imst she travelled to Innsbruck, arriving there on 22 December and spending Christmas with the old Duke and his young Duchess.[30]

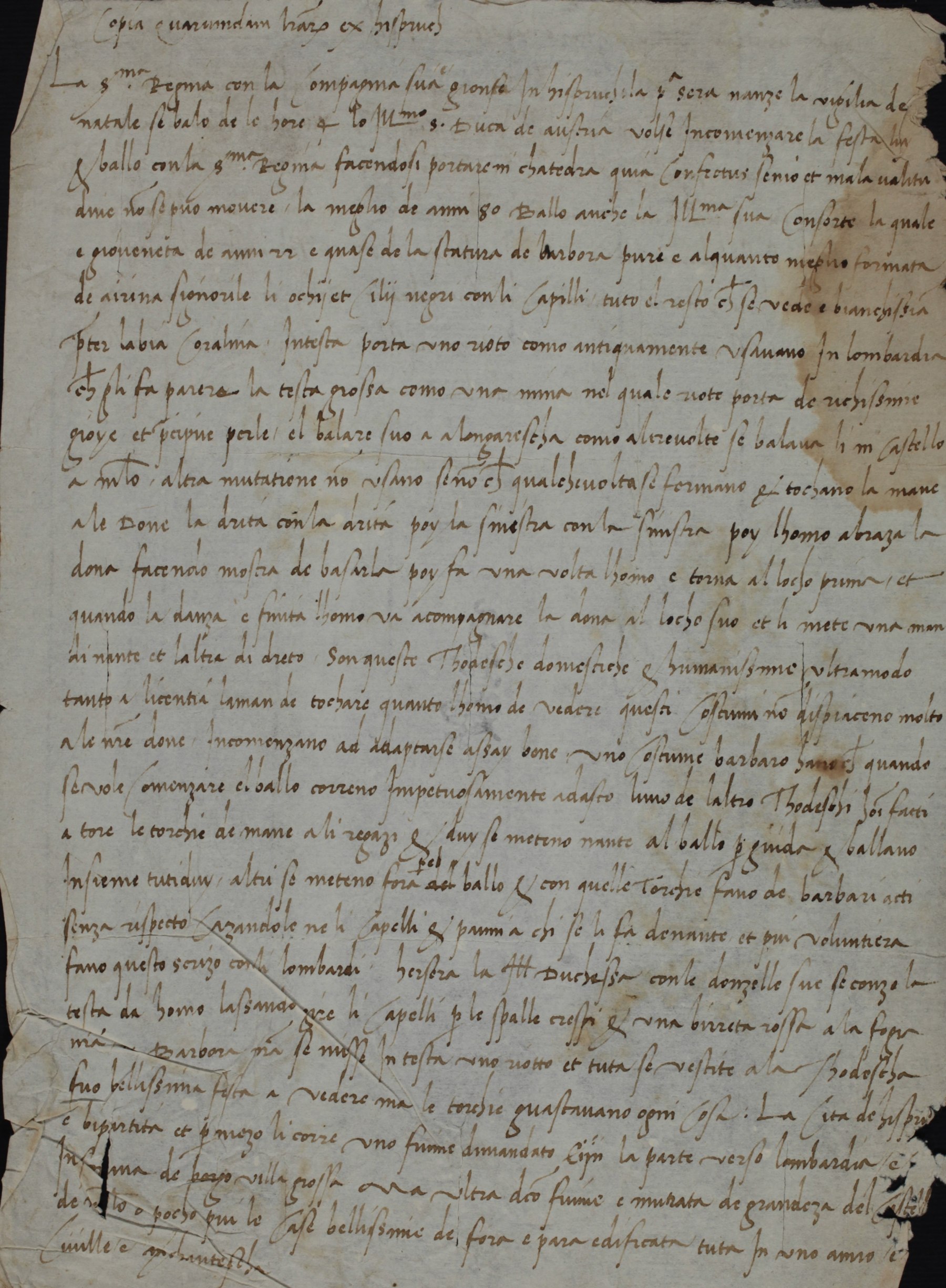

Such a politically significant union called for the fullest possible display of courtly entertainments as well as detailed reports of events by the envoys present. In ambassadorial correspondence of this period – normally so focussed on political matters – we therefore find regular references to the wedding celebrations, including the role of musicians therein. Reports of the Ferrarese envoys of Duke Ercole D’Este are particularly illuminating in this respect. In December 1493, for example, his ambassadors reported home on the dancing that had been held in honour of the new queen on 24 December, following her arrival in Innsbruck (see » Abb. Letter from the Ferrarese ambassadors):[31]

(The most serene queen reached Innsbruck with her entourage. The following evening, before Christmas Eve, they danced from four o’clock. His most illustrious Lordship, the Duke of Austria wanted to start the festivities and dance with the most serene queen. He was carried there in a chaise as he is elderly, in poor health and cannot move well. He is over 80 [recte 66] years old. His most illustrious consort also danced, who is a young lady of 22 [recte 25] years old and almost of a Barbaric [i.e. Germanic] stature, yet she is somewhat better formed and has a noble air, the eyes and brows black like the hair, everything else that is visible is perfect white, apart from the coralline lips. On the head she is wearing a wreath as they used to wear in Lombardy in ancient times, which makes her head appear large like a bomb, on which wreath she has the richest jewels and exquisite pearls. Their dance is the alongaresca [Hungarian dance], as is sometimes danced in the castle in Milan; they did not make any changes, except that sometimes they stop and touch hands with the ladies, the right with the right, then the left with the left, then the man embraces the lady as if to kiss her. The man then makes a turn and returns to his place. And once this dance (movement) is finished, the man accompanies the lady to her place, placing one hand in front, and the other behind her.

These German ladies are exceedingly accommodating and humane, as much for the licence of touching hands as for letting the men see; these customs do not displease our ladies much, they begin to adapt themselves very well to having a barbaric custom. When they wish to begin the dancing, the German men are running impetuously and in contest with one another, in order to tear away the torches from the boys, and two of them place themselves in front of the dance to lead, and the two dance together; others place themselves outside the dance and with these torches do gross acts without respect, making them catch hair and clothes of those in front, and preferably they do this trick to the Lombards. Yesterday evening the Illustrious Duchess with her ladies dressed their heads as men, letting their hair tumble down freely over the shoulders and wearing red berets of a wild and barbaric form; previously she had placed a face-mask on her head, and dressed herself all in the German fashion. It was a beautiful feast to see, but the torches damaged everything. The city of Innsbruck is bipartite and through the middle there runs a river called the Inn; the part towards Lombardy is in the guise of a large market town but the city across the river is walled all around the castle and somewhat beyond, the houses looking beautiful from the outside, and it all seems built in a single year, civilised and enchanting.)

Entertainments under Sigmund and Katharina

Sigmund and Katharina made every effort to accommodate Bianca Maria in the utmost comfort, the dances described by the Ferrarese ambassador being just one example of the courtly festivities held in her honour: in addition to “L’Ungaresca” dance mentioned here – a ballo in the Hungarian style known to have been performed at the Milanese court – the second page of this letter (not shown here) mentions another dance: “qua se fa uno Ballo dimandato pizighitone al quale le m[ilanes]e non stiano adaptarse” (here they have a dance called the Pizighitone, which the Milanese cannot get used to).[32]

On 28 December, the queen herself wrote to her uncle Ludovico Sforza (“Il Moro”) of the festivities over the Christmas period, and the time she had spent with the Archduchess, including their participation in dancing and games, in public and private: “partly on dancing and partly on seeing the aforementioned Lady Archduchess playing with a few other noblemen and cavaliers of hers and of ours. These feasts are sometimes done in public and sometimes privately in our chamber.”[33]). Maximilian’s Secretary Oswald von Hausen wrote to his colleague Zyprian von Serntein of Bianca Maria’s enjoyment of the dances at court, especially those in the Italian style, noting that the Italian ladies danced with such light feet, as if “auf ayrn, das die nicht prächn” (“on eggs, that they should not break).[34] Maximilian also received news of the festivities, and Bianca Maria’s growing friendship with Katharina (despite their lack of knowledge of each other’s native tongue), from Eitel Friedrich, the Count of Hohenzollern:

So sind bede Ewr mt. gemahell und die herczogin gutt gespillen wan sy nur mitt ain ander reden konden doch kartend sy und danczen mitt ain ander und sechen dem renen und stechen zu.

(Both Your Majesty’s wife and the Duchess have become good friends. If only they could speak with each other. Yet they play cards and dance with each other and watch the jousts).[35]The two women shared a love of music. In 1486 payments were made to the lute-maker Erhart Pöcht in Arzl near Innsbruck “umb ain Lauten, umb ain Fuetral auch etlich Sayten meiner gnedigen Frauen” (i.e. Katharina) and again “umb zwo Lauten mit Futraln” for her;[36] in 1506 Bianca Maria wrote to Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua, requesting that she send a clavichord to her, as there was none to be found in Innsbruck.[37]

Musicians for dance music

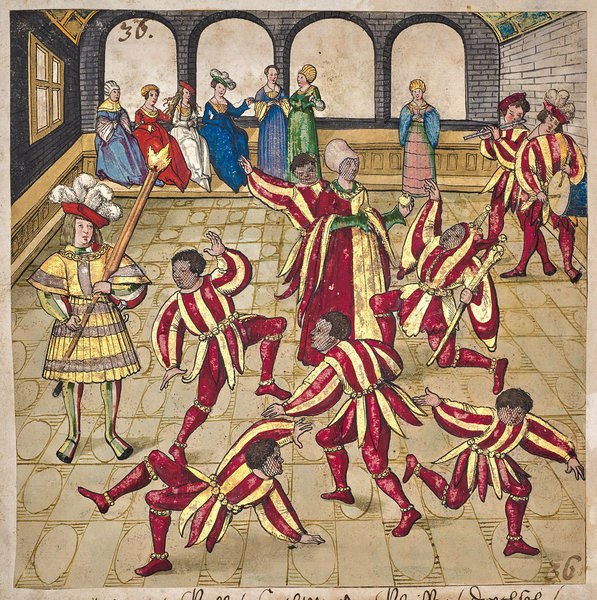

While these accounts give no information about the instrumentalists who provided the music for the dancing, it would seem that piper and drummer duos (» Instrumentenmuseum. Einhandflöte & Trommel) were commonly employed for this purpose at Maximilian’s court. In 1491, for example, a piper and a drummer, Hans and Matheus, received payment “als sy die vergangen vassnacht zu Hof zu Tanz gemacht haben.“[38] (for performing for the dance at court the previous Shrovetide) and the following year the same piper (named as “Hans Hertlin”) was rewarded “das er die vassnacht gehofirt hat”[39] (for performing for Shrovetide). A similar payment to both piper and drummer followed in 1493 “von wegen des Tanzmachens in vergangner Vasnacht” (for the dance the previous Shrovetide) and in 1496, Conrad, a piper, and “Härtly”, a drummer, were paid “von wegen etlicher Zeit, so sy bei Hof Tanz gemacht haben” (for having made dance at court several times).[40] Several of these performances would have accompanied Shrovetide (“Vasnacht”) mummeries rather than social dancing (see » Abb. A courtly Vasnacht dance). Other musicians were certainly involved in the 1493-4 revels held for Bianca Maria: on 29 December, Sigmund and Katharina honoured their guest with a grand banquet, although the Archduke himself was not present. The first of nineteen courses was announced to the sound of trumpets, and musicians of the court continued to perform during the meal, including “a female dwarf, who had a fine soprano voice”.[41]

Maximilian in Innsbruck

After two months awaiting Maximilian’s departure from Vienna, on 9 March 1494, Bianca Maria travelled with Sigmund and Katharina by boat on the River Inn to the nearby town of Hall, where, that same evening, she met Maximilian for the first time. Maximilian and his wife remained in Hall for a number of days, participating in games and dances. On 12 March, the wedding party, including a number of German and Italian nobleman, arrived in Innsbruck for what would be the culmination of the wedding festivities: a Mass performed in Innsbruck’s church on 16 March. It is the Ferrarese ambassador who again provides important information about the church service. In his letter dated 18 March 1494, the Ferrarese envoy Pandolfo Collenuccio wrote to Duke Ercole d’Este of the events of the previous days, noting:

“Per Poi la Copulatione de la Mta. Del Ré: Fatta Domenica. 9. del p[resen]te: la nocte seguente […] con la Regina In Halla: [… ] Giugó el di qualche poco a charte con la Regina. E similmente la sera se ballò a la domestica. […] Mercord. 12. Sua Mta. con la Regina se ne Vennero qui in Inspruch.” [42]

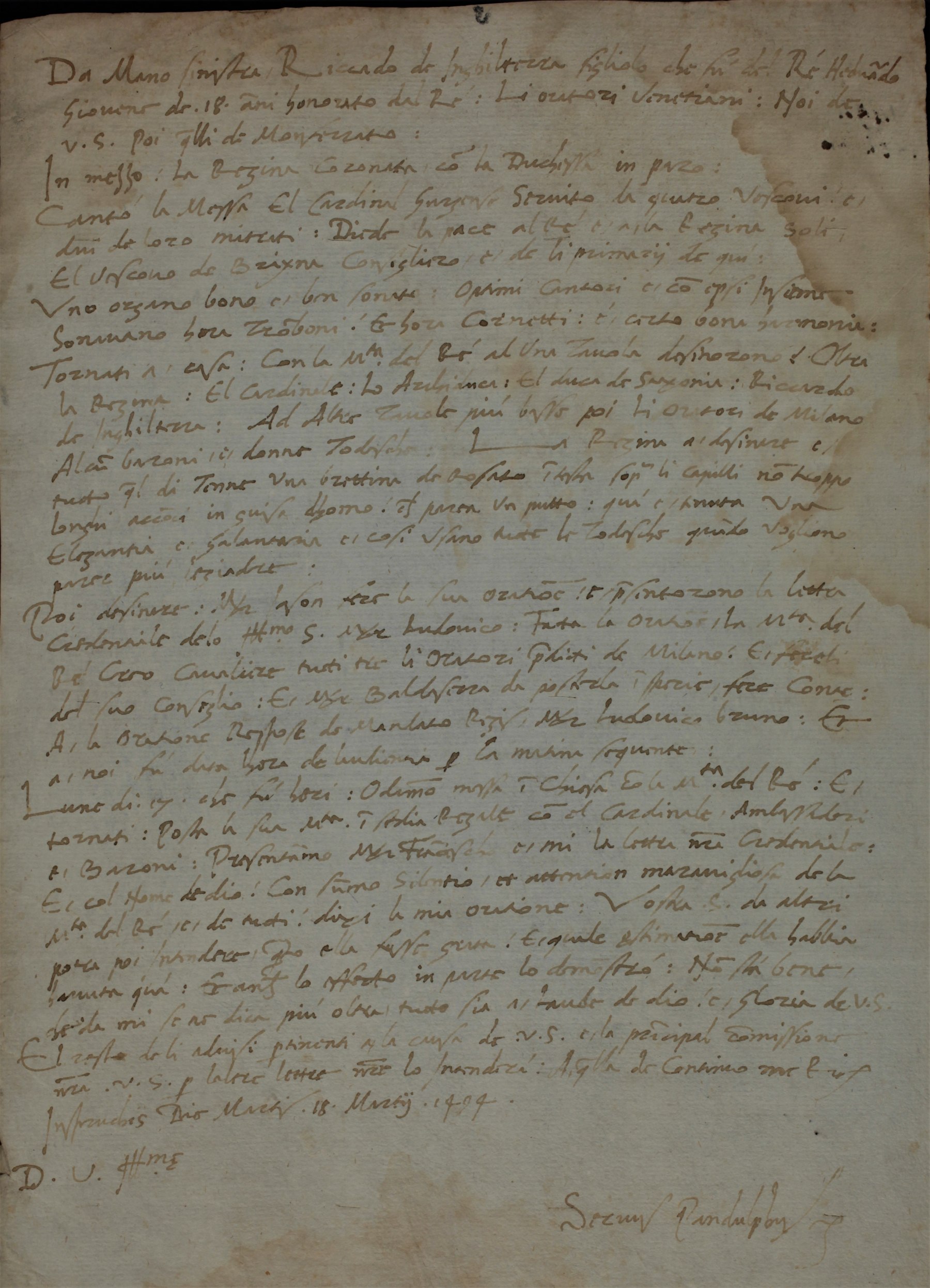

(For the wedding of his Majesty the King on Sunday 9 of this month: the following night [after arriving] in Hall he played cards for a while with the Queen. Likewise, in the evening they danced in the native fashion […] Wednesday 12 his Majesty with the Queen came here to Innsbruck.)Collenuccio then goes on to describe the procession to St Jacob’s of lords and barons, as well as envoys from Montferrat, Ferrara and Venice. The Queen, wearing a crown, was led by Duke Albrecht of Saxony and Margrave Christoph of Baden while Archduke Sigmund was carried in a sedan chair. His wife Katharina was described as being covered in pearls “from head to toe” (“da capo a piede”). Yet, it is the second page of Collenuccio’s letter that provides important information about the music performed in the church (see » Abb. Letter from Pandolfo Collenuccio)

At the top of this page Collenuccio writes:

Da Mano sinistra, Riccardo de Inghilterra figliolo che fù del Ré Heduardo Giovene de 18 anni honorato dal Ré: Li oratori Venetiani: Noi de V. S. Poi q[ue]lli de Monferrato:

In mezzo: La Regina Coronata, con la Duchessa in paio:

Cantó la Messa El Cardinal Gurzense Servito da quatro Vescovi: e dui de loro mitrati: Diede la pace al Ré e alla Regina soli El Vescovo de Brixna Consigliero e de li primarij de qui:

Uno organo bono e ben sonato: Optimi Cantori e con epsi insieme sonuano hora Tromboni. Et hora Cornetti: è certo bona harmonia:(On the left-hand side, Richard of England, son of King Edward,[43] a youth of 18 years old honoured by the King; the Venetian envoys; we of Your Lordship, then those of Montferrat. In the middle, the queen, wearing a crown, paired with the duchess.

The Cardinal of Gurk sang the Mass served by four Bishops and two of their prelates. The Bishop of Brixen, principal councillor here, gave the sign of peace to the King and Queen. A fine organ was played well. Excellent singers, and with them, the trombones now played. And then the cornetti. There was certainly a fine harmony.)Here we therefore find an example of the practice of trombone and cornett performing together with the choir. This would become a feature of liturgical services at Maximilian’s court, albeit reserved for ceremonies of particular importance. In fact, this combination of wind instruments with the Hofkantorei was represented years later in the woodcuts for Maximilian’s Triumphzug (» I. Instrumentalkünstler). Performances of Maximilian’s choir with trombone and cornett also occurred in the churches of cities that the king visited on his travels, such as Augsburg.[44]

Instrumentalists in the church service of 16 March 1494

It is not possible to identify all the musicians who performed in the church service of 1494 described by Collenuccio. When Maximilian inherited the Tyrol, payments to the choristers of St Jacob’s, who had provided the music for liturgical services of Sigmund’s reign, stopped. Maximilian presumably brought his own group of singers with him to Innsbruck: in the early years of his reign (and before he moved his Kapelle to Vienna in 1498), the king is known to have had a travelling group of eight singers in his employ, who were paid in various cities in southern Germany during the early 1490s.[45] Furthermore, a group of singers accompanied the King on his travels to the Low Countries in 1494, which followed soon after the celebrations in Innsbruck described by Collenuccio. On 24 August 1494, Maximilian, Bianca Maria, and Maximilian’s son Philip, Duke of Burgundy, attended Mass in Mechelen, where „Da ward von des Königs oberländischen und französischen Singern ein köstlich Meß gesungen“ (a splendid Mass was sung by the King’s “oberländisch” and French singers).[46] The use of the term “oberländisch” here implies that these musicians were in some way affiliated to Maximilian’s Upper Austrian lands, and presumably sang for him, and Bianca Maria, in Innsbruck.[47]

The identities of the instrumentalists who performed in Innsbruck’s church on 16 March are also not entirely clear: the account books of the court for 1493-4 list only seven trumpeters, a trombonist (Conrad Kayser), a drummer as well as the organist Hofhaimer, who presumably played on the “fine organ” described by Collenuccio[48]. The construction and upkeep of the organs of the church appear to have been of particular interest to Maximilian: a number of instruments were built there under his instruction (including one erected under Hofhaimer’s supervision in 1491 and 1492) and there are numerous references in court records to the building and maintenance of these notable instruments (» C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik).[49]

There is no specific mention of cornettists or additional trombonists in the Innsbruck accounts of 1494. However, civic payment lists do make reference to players on trombone and cornett who were in Maximilian’s employ at that time. For example, Augsburg city council made payment to “Augustin Schubinger, der k. Mt. trumbetter” in February 1495 and then to “Hans Sturtzenbacher, des Rö. kunigs zinggenplaser” (cornettist) in autumn 1495,[50] neither of whom are listed in the accounts of Maximilian’s court for that year. Schubinger, trombonist in the Augsburg civic ensemble during the early 1480s, had been named as the “kaysers busaner” (i.e. the trombonist of Maximilian’s father, Friedrich III) when visiting the city in 1488.[51] Following a brief appointment, until 1493, in the civic ensemble of Florence, he appears to have returned to the service of the Imperial court, being identified in various civic and court payments as the King’s trombonist, trumpeter, piper, as well as cornettist.[52] Little is known of Hans Sturtzenbacher: in the Augsburg accounts of 1507, he is identified as a “pfeyffer von Sterzinng” and in those of the following year as being “von Innsprugk”.[53] An unnamed cornettist belonging to the King likewise played in Basel in 1495.[54] Whether any of these musicians performed for Maximilian’s wedding celebrations in Innsbruck is difficult to ascertain owing to the nature of their work for the royal court. Many instrumentalists seem to have been employed by Maximilian on an ad hoc basis, the King calling on their services when suitable occasions arose. The musicians, meanwhile, retained their association with the King, even when absent from court.

The Visit of Philip the Fair

The incorporation of wind instruments into performances of liturgical music was witnessed again in Innsbruck during the visit of Maximilian’s son, Philip, in 1503 (see » Abb. Philip the Fair of Burgundy, King of Spain). By that time, circumstances at the Innsbruck palace had changed yet again. Archduke Sigmund had died in 1496 and his widow Katharina soon remarried, the Neuhof that they had inhabited being transformed soon thereafter into Maximilian’s treasury and adorned with its golden roof. There was therefore now no continuous ducal presence, as there had been during Sigmund’s lifetime, although through Maximilian’s regular visits to Innsbruck, courtly music was still often heard within the palace walls.[55] As Maximilian’s visits to Innsbruck continued, so too did the descriptions of life at his court, written by those who visited the king from other European centres. One such visitor was Antoine de Lalaing, a Flemish nobleman and courtier in the entourage of Philip the Fair that accompanied the Burgundian duke on the two-year journey that took him from Mechelen to Spain and back again, via France, Austria and Maximilian I’s German territories. Antoine documented these travels in great detail in his journal, including the musical performances that took place in Innsbruck after the Burgundians’ arrival there on 13 September 1503.[56]

Church music at St Jacob’s

Like Collenuccio a few years earlier, Lalaing was impressed by the organ he heard played in St Jacob’s church in the town. The nobleman wrote in his journal that “L’église parochiale de la ville a unes orghes, les plus belles et les plus exquises que jamais je véy. Il n’est instrument du monde quy n’y joue: car ils sont tous là-dedens compris, et coustèrent plus de dix milles francs au faire” (The parish church of the town has an organ that is the finest and most exquisite that I have ever seen. There is no instrument[al sound] in the world that this does not play, for they are all contained therein; it cost more than 10,000 francs to be made).[57] This was not, however, the same instrument that had been built under Hofhaimer’s supervision in 1491-2, for a new organ had been installed by Wolfgang Reichenauer in 1497-8: on 6 March 1498 payment was made to: “Wolfgangen Reychenauern, Orglmacher, so die neu Orgl zu Ynnsprugg macht”.[58] Renovations and replacements of the organ continued in later years, garnering praise from another visitor to Innsbruck in 1517. That year, the secretary to Cardinal Luigi of Aragon, Antonio de Beatis, remarked: „In der Hauptkirche steht eine wunderschöne Orgel “nicht besonders groß, aber mit vielen Registern und vorzüglichen Stimmen … ein wahrhaft liebliches und sinnreiches Werk, wie wir in solcher Vollkommenheit auf der ganzen Reise keines mehr gesehen haben” (In the main church there is a wonderful organ that is not particularly big but has many registers and exquisite voices – a truly charming and ingenious device, the perfection of which we did not encounter anywhere else on our journey).[59]

Not only the fine organ of St Jacob’s impressed Lalaing: Maximilian’s chapel choir was also in Innsbruck for Philip’s visit. On 1 October he reported having heard a Mass “à la grande église, chantée des chantres du roy” (at the great church [i.e. St Jacob’s], sung by the king’s singers).[60] However, Maximilian’s singers were not the only individuals whom Lalaing heard sing in Innsbruck, for the chapel of the Burgundian court had joined their Duke on his travels to Austria. On 15 September, Philip’s choir had sung in the parish church in Hall, for a Mass attended by Philip, Maximilian and nobility of both their courts: “Le venredi ouyrent la messe ensamble, avec grande noblesse d’Allemaigne et des pays de Monseigneur, à la grande église de Halle, laquèle chantèrent les chantres de Monseigneur” (On Friday they heard Mass together, with the high nobility from Germany and his Lordship’s lands, in the great church of Hall, sung by the singers of his Lordship [i.e. Philip]).[61] Then, on 21 September, this was repeated: “Le joedi … le roy et Monseigneur, acompaigniés de grands maistres et de nobles, oyrent la messe à la grande église de Halle, chantée par les chantres de Monseigneur.”[62] The list of 22 chapel members prepared before Philip’s departure for his travels, on 1 November 1501, included twelve chaplains (with the organist, Henry Bredemers) under the leadership of the first chaplain and his deputy.[63]

It was, however, the performances of Philip’s and Maximilian’s choirs together which appear to have been particularly remarkable. On 17 September, Maximilian and Philip heard Mass at the church of St Jacob, sung by both the royal choir and that of the visiting duke (“les chantres du roy et de Monseigneur chantèrent la messe”) and accompanied by the organ in all its registers (“et jouèrent les orghes plaines de tous instrumens”) – a performance that Lalaing deemed “la plus mélodieuse chose que l’on pourroit oyr” (the most melodious thing that could be heard).[64] A similarly impressive performance followed just over a week later. On 25 September, Maximilian, Bianca Maria and Philip were again in St Jacob’s for the memorial service for Hermes Maria Sforza, a brother of the queen. The following day they returned to the church, whereupon two Masses were sung: the first, a Requiem, by Philip’s choir (“les chantres de Monsigneur”) and the second, “de l’Assumption Nostre-Dame” sung by the King’s choir (“les chantres du roy”). On this occasion the performance was further enhanced by the use of the king’s trombonists who began the Gradual and played the Deo gratias and Ite missa est while Philip’s choir sang the Offertory (“Et comenchèrent le Grade les sacqueboutes du roy, et jouèrent le Deo gratias et Ite missa est, et les chantres de Monseigneur chantèrent l’Offertoire”).[65] It is possible that the famous composer Jacob Obrecht was present at the event (see » G. Jacob Obrecht).

As with the performance for the wedding celebrations of March 1494, it is not clear how many trombonists played on this occasion, or who, indeed, these were. Maximilian seems to have had a number in his service at that time: in 1503, the Augsburg council made payment to “ko.Mt. busaner Jobsten Nagel” and “ko. Mt. busanern iro fünffen” (his royal majesty’s five trombonists) and the following year, listed “Jörigen Holland, Jorigen Eyselin, Hannsen Stewdlin vnd Vlrich Vellen, kö. Mayt. Busanern” as well as “kö. Mayt. busanern Enndressen vnd Jorigen Nagel”.[66] Additionally, a 1503 entry in Maximilian’s Gedenkbuch is indicative of the trombonist Hans Neuschel’s presence in Innsbruck (here identified as ‘ Hans Meüschel’): “Wir haben vnnserm Pusauner Hannsen Meüschel haimtzuziehen erlaubt” (We have allowed our trombonist, Hans Meuschel, to return home).[67] Augustin Schubinger, mentioned earlier, was by that time in Philip’s employ, and from around 1500 had seemingly made the cornetto, rather than the trombone, his instrument of choice. Schubinger was known to have performed together with Philip’s choir in this capacity and he may in fact have done so during this 1503 visit to Innsbruck. He certainly accompanied Philip on this European tour: when the Duke visited the court of Ferdinand and Isabella in Toledo in May 1502, then that of his sister Margaret and Philibert of Savoy in April 1503, Lalaing wrote of the choir’s performances at the two courts, noting the brilliance of Augustin’s playing.[68]

Jousts and dances for Philip

As with the entertainments provided by Sigmund for Bianca Maria a few years earlier, Maximilian gave the fullest possible display of the revels of his court to his son. On the evening of 17 September, the esteemed guests were entertained by a banquet and then dancing. After they had supped together, as Lalaing describes, there was a dance in the German style with Swiss drums and trumpets. Four torchbearers accompanied first the King and one of the ladies of the court, and then Philip and Bianca Maria:

Là se firent les danses à la mode d’Allemaigne, aux tambourins de Suysses et trompettes, et mena le roy danser une des dames de la royne, où IIII ducs portoient les torses. Celle danse faillie, Monseigneur mena la royne danser, où IIII aultres grands maistres portoient les torses.[69]

(There they danced in the German fashion, with Swiss tambourins and trumpets, and the King led one of the ladies of the Queen to the dance, while four dukes carried the torches. When this dance had ended, his Lordship led the Queen to the dance, and four other great lords carried the torches.)

On 1 October, another banquet and dance took place in Innsbruck, the day likewise concluding with a torch dance, in which the royal party participated. This ended with “une danse appellée ung bransle, à la mode d’Allemaigne, aux tambourins de Suysses et à trompettes” (a dance called a bransle, in the German style, with Swiss drums and trumpets).[70] It is noticeable that here, the dances were not apparently accompanied by the above-mentioned pipe and drum, but by trumpets and Swiss side-drums.

The courtly dances that had been such a key part of the entertainments provided for Bianca Maria thus continued in the Innsbruck palace in the years that followed, this time in Maximilian’s presence (see » H. Civic and courtly dancing). The diaries of the Venetian secretary Marino Sanuto, who visited Innsbruck earlier in 1502, provide insight into the dances performed there for Shrovetide, which Maximilian often celebrated in Innsbruck.[71] On 13 February, for example, Sanuto described a joust that had been held on the main town square in front of the balcony with its golden roof, the area having been boarded off and covered with sand. The participants entered the ring to the sound of many trumpets (“con molti trombeti”) and following the competition, as was customary (and reported in other accounts by the Venetian official), there was a dance for the king and his guests.[72] The nature of the dances performed on these occasions is indicated in another entry in Sanuto’s diaries. A few days earlier, on 24 January, following the joust and evening meal, revels were held in the palace, in which two masked queens entered the room. One of the earls present, accompanied by trumpeters and a herald (“acompagnato da molti trombeti et uno araldo”) led one of the queens in a dance, while Maximilian did the same with the other queen, who was “acompagnata da alguni homeni salvatici” (accompanied by several wild men).[73] On 20 January, Sanuto described another four jousts in which the king participated, and then an evening entertainment – a masque – where, in a large hall, seven combatants competed for an abandoned queen. The Venetian commented that this grand spectacle was accompanied by “the most perfect music” (“musicha perfetissima”) performed by certain “wild men” (“homeni salvatici”) on what Sanuto describes as “horns” (“corni”).[74]

Conclusion: Innsbruck in Maximilian’s realm

Following the succession of Maximilian to Sigmund of Tyrol as Archduke of Upper Austria in 1490, life within the Innsbruck palace was subject to a number of changes. While Sigmund’s court was permanently based in Innsbruck, Maximilian was repeatedly absent from this would-be residence. The political complexities of his reign required the king to endure a nomadic lifestyle, together with the many court officials – including musicians – who accompanied him on his travels. Innsbruck thus became one of many towns to play host to the itinerant ruler, albeit one that he favoured above other areas of his vast empire.[75] Although the reigns of Sigmund and Maximilian differed significantly in their nature, music was a key feature of both their courts and was of great importance to both Archdukes. In contrast to the permanence of Sigmund’s residence in Innsbruck, which would have encouraged regular music-making in the palace, town and surrounding area, the king’s presence in the Tyrol was more sporadic, and therefore so too were performances by his musicians in the region. When Maximilian was in residence, the town became both the political and cultural centre of the king’s dominions, the ambassadors who visited the king witnessing performances by some of the most significant performers of the age, such as Augustin Schubinger and Paul Hofhaimer. Diplomatic and musical exchanges were thus entwined as guests of the court were presented with local musical and cultural practices, while Maximilian and his court were introduced to foreign musicians and dances. The life of the court also spilled beyond the palace walls, onto the town square which acted as a tiltyard for the many jousts that entertained the king’s guests, and the parish church which doubled as the court chapel. Innsbruck remained important to Maximilian for the rest of his life. Even after he began to develop Vienna as the capital of his Empire, he repeatedly returned to his Tyrolean home, bidding the town a final farewell in November 1518.

[1] Maximilian was elected King of the Romans in 1486. He succeeded his father, Friedrich III, as head of the House of Habsburg in 1493, but only received the title of Emperor in 1508. For clarity, he will be referred to here as king. At this time, Upper Austria (“Oberösterreich”) comprised Tyrol, parts of the Upper Rhine, East Swabia, Alsace and the Vorlande at the east end of Lake Constance: see Benecke 1982, 35; Wiesflecker-Friedhuber 1996, 131f.

[2] Benecke 1982, pp. 35-6; Wiesflecker-Friedhuber 2005, 126f.

[3] „…ihn herrlich empfienge, und unter andern Kurzweilen, zu den Tyrolischen Fundgruben führte“. Birken 1668, 1012.

[4] See, for example, Drexel 2001, 603; Höpfel 1989, 20.

[5] “Deren Gewerkleute, an der zahl 7400, unter fliegendem Fahn in schöner ordnung, ihnen entgegen kamen, und nach des Erzherzogen befehl, vor dem Röm. König sich auf die kniehe warfen.” Birken 1668, 1012f.

[6] “Sie brachten ihm auch Geschenke, etliche güldene Schüsseln voll Rheinischer Goldgulden, und ungearbeitetes Silber bey 100 Pfunde. Es kamen auch Venedische Gesandten, die ihn, mit Widergabe etlicher dem Erzhaus vordessen abgenommenen Plätze, zu versöhnen begehrten: weil sie vernommen hatten, daß sie ihn forthin zum Nachbarn haben würden.“ Birken 1668, 1012f.

[7] “Rhætica dum tellus vult se summittere Summo Æmilio, fossor prævius ecce venit. Aurea, se talem tali probat, illa, ministro: hinc auro plenas obtulit iste manûs.” Birken 1668, 1013. I would like to thank Alison Samuels for the translation of this epigram and James Robson for further advice about its meaning.

[8] “Tyrol sein Bergleut-Heer dem Helden schickt entgegen, itzt da es selbst sich will zu dessen füssen legen. Es heiset ihn willkomm durch Gold in ihrer Hand: Weil es, durch ihren Fleis, sich weist ein güldnes Land.” Birken 1668, 1012.

[9] “Aber Erzh. Sigmund, der nun ein hohes Alter auf sich, und keinen Leibs Erben mehr zuhoffen hatte, auch zu den Regirungssorgen verdrossen war, beschickte seine Landstände nach Insbruck, sprache sie ledig von ihrer Eidspflicht, und hiesse sie dem Röm. König, als ihrem angehenden Landsfürsten, schwören, den er, in ihrer gegenwart, an Sohns stat aufnahme, ihm alle von Vatter ererbte Länder abtratte und übergabe…” Birken 1668, 1013.

[10] Wiesflecker-Friedhuber 2005, 128. See also Jäger 1874.

[11] Drexel 2001, 602-3; Senn 1954, 1-2.

[12] For the Mitterhof, see » Leitbild F. with commentary. Further details of Maximilian’s relationship with Innsbruck are in Senn 1954, 19; Fritz 1968; Cuyler 1973; Benecke 1982; Wiesflecker-Friedhuber 1996 and 2005.

[13] Felix Faber (1923, 33): “In dieselbe [Innsbruck] eingetreten, fanden wir sie voll von Adeligen und Bewaffneten. Fürsten, Grafen und Barone waren zum Erzherzog gekommen, denn gerade feierte der Landesfürst mit der Tochter des Sachsenherzogs Hochzeit; zu dieser Feier war der Adel aus ganz Deutschland zusammengeströmt.”

[17] A tun of wine was awarded to the organist in January 1498: see Wiesflecker 1993, 269 (no. 5756).

[18] Wiesflecker 1993, p. 222 (no. 5364).

[19] Busch-Salmen 1992, pp. 64f.; Schuler 1995, 13.

[20] See also » I. The court chapel of Maximilian I.

[22] The Triumphzug was never completed, and its woodcut images therefore include a number of empty banners, which were to contain phrases introducing many of the personnel presented. However, the intended content of the plaques can be reconstructed from the initial manuscript programme for the images, which was dictated by Maximilian himself and refers to several musicians by name.

[24] For example, the Augsburg civic accounts of 1490 include payment of: “4 fl. des kunigs zwayen luttenschlager, Artus vnd Lenhart”. D-Asa (Stadtarchiv Augsburg), Baumeisterbücher Nr. 84 (1490), fol. 17r.

[28] Wiesflecker 1971-1986, vol. 5, 401-2.

[29] Weiss 2010, 56.

[30] Hochrinner 1966, 33-39.

[31] Archivio di Stato di Modena est disp amb germ, busta 1, undated letter, recto. A summary of the letter is presented in Regesta Imperii Online XIV,1 n. 2877: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1493-12-24_1_0_14_1_0_2882_2877 (accessed 01.11.2019).

[32] Archivio di Stato di Modena est disp amb germ, busta 1, undated letter, verso. A summary of the letter is presented in Regesta Imperii Online XIV,1 n. 2877: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1493-12-24_1_0_14_1_0_2882_2877 (accessed 01.11.2019). Dances at Maximilian’s court will be discussed further in » I. Civic and courtly dancing.

[33] „parte in ballare e parte in videre zugare la prefata Domina Archiducesa con alchuni altri Signori et cavaleri de li suoi et de li nostri. E queste feste qualchi volta sono facte in publico, et qualchi volta privatamente ne la camera nostra.“ Calvi 1888, 48.

[34] Tiroler Landesarchiv Innsbruck (A-Ila), Maximiliana XIV/1493, fol. 103. Summary in Regesta Imperii Online,

RI XIV,1 n. 2878: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1493-12-24_2_0_14_1_0_2883_2878 (accessed 01.11.2019).

[35] Quoted in: Köfler and Caramelle 1982, 208.

[37] Regesta Imperii XIV Nr. 25967: Archivio di Stato di Mantova, Agonz, E/II/2, busta 429, Nr 6.

[38] Waldner 1897/98, 11.

[39] Waldner 1897/98, 14.

[41] Hochrinner 1966, 44.

[42] Pandolfo Collenuccio, Innsbruck, to Ercole d’Este, 18 March 1494: Archivio di Stato di Modena dis amb germ, busta 1, recto. Summary of the letter in: Regesta Imperii Online, RI XIV,1 n. 478: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1494-03-16_1_0_14_1_0_482_478. See also Wiesflecker Bd. I, 368.

[43] This was Perkin Warbeck, pretender to the English throne, who claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the missing second son of Edward IV.

[44] See Green 2012; Grassl 2019.

[46] Quoted in Meconi 2003, 27.

[47] Further on Maximilian’s chapel singers, see » I. The court chapel of Maximilian I.

[48] Waldner 1897/98, 20-21.

[49] Senn 1954, 39–44; See also Waldner 1897/98, 33–34.

[53] D-Asa (Stadtarchiv Augsburg), Baumeisterbücher Nr. 101 (1507), fol. 24v and Nr. 102 (1508), fol. 24v.

[55] Indeed, from 1516 until 1521, the two young princesses Anna of Hungary and Maria of Austria were resident at the Innsbruck palace and had several musicians in their employ. See Waldner 1897/98, 59 and Senn 1954, 46–47.

[56] Gachard 1876, 309.

[57] Gachard 1876, 310.

[58] Senn 1954, 39-40, also regarding the subsequent repair of the organ by Balthasar Streng in 1502.

[60] Gachard 1876, 319.

[61] Gachard 1876, 311.

[62] Gachard 1876, 315.

[63] Meconi 2003, 62.

[64] Gachard 1876, 313.

[65] Gachard 1876, 316–317.

[66] D-Asa (Stadtarchiv Augsburg), Baumeisterbücher Nr. 97 (1503), fol. 28r and Nr. 98 (1504), fol. 26r-v.

[67] Wessely 1956, 111.

[68] Meconi 2003, 35. See » I. Instrumentalkünstler; » G. Augustin Schubinger.

[69] Gachard 1876, 314.

[70] Gachard 1876, 320.

[71] Sanuto’s diaries are published in Barozzi 1880.

[72] Barozzi 1880, column 217.

[73] Barozzi 1880, column 216.

[74] Barozzi 1880, column 215.

[75] According to Benecke 1982, 94, Maximilian visited Innsbruck 22 times between 1498 and 1518.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Helen Coffey: „Music and ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/music-and-ceremony-maximilians-innsbruck> (2019).