Civic and courtly dancing

Dances for the Queen of the Romans

In the spring of 1494, Maximilian I, King of the Romans, embarked on the first expedition across his German lands since the death of his father, Emperor Friedrich III, the previous year. The journey was of great political and personal significance to the 35-year-old king, who was now the sole ruler of the Holy Roman Empire. It not only enabled Maximilian to renew the privileges, rights and taxes that his father had put in place across their German territories, but also allowed him to finally meet again with his two children Philip and Margaret and relinquish rule over the Netherlands to his son, who had that year reached his majority. As ever, Maximilian would not have been alone on this journey, but was accompanied by an entourage of courtiers and servants. Yet additionally, for the first time, the king was joined on his travels by his wife, the new Queen of the Romans Bianca Maria Sforza. Just days after the celebration of their nuptials in Innsbruck on 12 March (» Kap. Maximilian in Innsbruck), Maximilian and Bianca Maria set out for the Netherlands, stopping on route at Füssen, Kempten, Speyer, Worms and Cologne.[1] On their way they were regaled with all kinds of festivities befitting a king and queen, including jousts, banquets, and also dances. They arrived in Worms in June and there, after the city had sworn their loyalty to the king and queen, Bianca Maria initiated a dance with the nobility and citizens who were present:

Da tantzten mit der konigin pfaltzgraf Philips churfurst zur lincken hand und tantzten 8 graven vor und nach mit fackeln züchtiglich umbher und etlich graven und herren mit hofjungfrawen nach; doch nicht viel teutsche täntz. Darnach den andern tantz tantzten andere fürsten graven und herren und edle mit hofjungfrawen und bürgerin manch tantz bisz nach mitternacht.[2]

(There, the Elector Count Palatine Philip danced with the Queen, to her left, and 8 Counts danced around demurely with torches, before and behind them, and a number of Counts and Lords danced behind them with ladies of the court; yet not many German dances. After that, for the second dance, other princes, counts and lords and nobles danced several dances with ladies of the court and town until after midnight.)

By July, the royal couple had reached the Netherlands where they met with the 16-year-old Philip and the 14-year-old Margaret. As in the German towns, the Flemish people celebrated the arrival of the newlyweds with festivities that reflected their royal status, and dances again played a part in this cultural and political exchange. A retrospective account of Georg Spalatin, Secretary to Elector Friedrich the Wise of Saxony, describes one such occasion in Mechelen in September that year, when the marriage of the Austrian nobleman Wolfgang von Polheim, to Johanna, daughter of the Netherlandish Count Wolfhart von Borsellen, was celebrated with a joust and then a dance:

Auf den Abend hat man einen Tanz auf dem Rathhaus halten wollen, dabei der König, die Königin und Prinz[ess]in mit beiden ihren Frauenzimmern und alle Fürsten gewesen. […] Haben durch einander Oberländisch, Niederländisch und Walisch, ein jeder nach seiner Manier, getanzt. Ist unserm g[nädigsten] Herrn Herzog Friderichen mit der Braut der erst Tanz gegeben. Der König hat sich auch mit etlichen den Seinen vermummelt und seltsam zugericht und ist also an den Tanz kommen.[3]

(In the evening a dance was to be held at the town hall, at which the King, Queen and Princess [Margaret] with their ladies, and all princes, were present. […] There was a mixture of ‘Oberländisch’, Netherlandish and Italian dances, each in its own style. Our most gracious lord Duke Friedrich performed the first dance with the bride. The King also came to the dance with a number of his people, in disguise and dressed strangely.)

Though the accounts of Maximilian’s and Bianca Maria’s experiences in Worms and Mechelen are not particularly detailed in their descriptions of the dances performed, both reports point to the importance of dance to the political and social interactions of the urban and courtly elite. Dances were executed regularly for all kinds of representative occasions in the cities and at court, whether for major celebrations such as for Shrovetide, weddings or jousts, or for other gatherings of the citizens and nobility such as during Imperial diets. References to dances in Maximilian’s territories are therefore not uncommon, featuring in diplomatic correspondence that sought to recount the King’s activities to his political counterparts, as well as in chronicles that documented notable events in court and civic life for posterity. The reports written in Worms and Mechelen are fairly typical in their level of detail as well as in the particular aspects of dances that they describe, the noteworthiness of these specific features of dance indicating the social and political significance that each of these possessed. Both accounts, for example, remark on the social-standing of the participants, identifying by name only those who, being of particular importance, took prime position in the dances enacted that day. The references to regional dance styles – ‘Oberländisch’, Netherlandish and Italian dances in Mechelen and ‘not many German dances’ in Worms – are also not unusual and reflect the existence of a repertoire of dances that was both stylistically diverse and understood by everyone – whether nobleman or citizen – who observed or danced with the King and Queen.

Basse Danse, Bassa Danza, Ballo

The engagement of Maximilian, Bianca Maria and their court with this core international repertoire of dances is already evidenced several years before their travels to Worms and Mechelen in 1494. In 1491, for example, Maximilian had participated in ‘mancherlei tentz auf welsche und niderlendische art’[4] (several dances in the Italian and Netherlandish style) while in Nuremberg, and in December 1493, shortly after her initial arrival in Innsbruck from Milan, Bianca Maria was reported as having danced ‘most beautifully in the French, Italian and German styles’.[5] While these accounts indicate the familiarity with which both King and Queen engaged with particular national dance styles, elsewhere we find evidence of local dance customs that challenged the participants with unfamiliar steps. For example, envoys of the Ferrarese court remarked on the Italian dances performed by Bianca Maria following her arrival in Innsbruck in December 1493, which included ‘the longaresca, as is sometimes danced in the castle in Milan’ (» I. Kap. The arrival of Bianca Maria Sforza). The Innsbruck courtiers then appear to have performed a dance unfamiliar to those recently arrived from the Sforza court, the Ferrarese ambassadors noting a performance of the ‘Pizighitone, which the Milanese cannot get used to’ (» I. Kap. Entertainments under Sigmund and Katharina). Despite these differences, a common repertoire of choreographic elements seems to have existed that allowed courtiers from various regions of Europe to engage with even unfamiliar dances.[6] For example, Barbara Crivelli Stampi, who had accompanied Bianca Maria from Italy to Innsbruck, apparently familiarised herself with the German dances she encountered there by relating these to the customary dances of Milan.[7]

The primary forms of dance performed at European courts at that time can be determined from several treatises of French, Burgundian and Italian origin, the earliest of which was written in the mid-15th century: no equivalent sources have been identified for the German-speaking lands for this period.[8] At the heart of the dance repertoire described in these treatises stood the basse danse associated with the Burgundian court, its Italian equivalent the bassa danza, and another Italian courtly dance form, the ballo. As reflected in its name, the Burgundian basse danse (literally ‘low dance’) was a steady, serene dance performed by one or more couples, often in procession, with steps low to the ground and lacking leaps or rapid movements. The basse danse had four basic dance steps (five if including the reverence – the bow by the male dancer at the start of each dance) which were strictly organised into a number of distinct patterns known as mesures. A single dance comprised several mesures, which were also carefully arranged so that different step patterns alternated with one other. During the fifteenth century, basse danses varied in their duration as a result of the various combinations of mesures that might be employed. However, as Daniel Heartz has established, treatises of the early sixteenth century point to the gradual emergence and eventual predominance of a standardised basse danse choreography.[9] Heartz also identifies a German off-shoot of the basse danse that appears to represent this later stage of the dance in its repetition of step patterns; this also introduced a distinctive syncopated rhythm in its musical accompaniment, not found in the Burgundian dance form (see » Kap. Urban Courtly Dance). Both the original and German adaptation of the basse danse were typically followed by an after-dance (called the ‘pas de brebant’ in the Netherlands) that was twice as fast as the original dance and allowed for quicker movements and small leaps.[10]

The Italian bassa danza similarly promoted grace and elegance in the dancers’ movements but allowed for greater choreographic freedom in its application of nine different dance steps. The Italian dancers were not restricted to performing in pairs (as in the basse danse) but in various combinations and they also executed dance figures that entailed, for example, brief moments of separation and reunion, or the exchange of dancers’ places.[11] Furthermore, while the bassa danza, like the basse danse, employed a single, steady metre throughout, it might include sections that drew on the faster metres and movements (including jumps and leaps) of the three other primary dance forms associated with the Italian courts: the ‘quarternaria’ (a sixth faster than the bassa danza, and also referred to as the ‘saltarello tedesco’ due to its alleged popularity with the Germans), the ‘saltarello’ (the customary after-dance of the bassa danza at two-sixths faster) and the ‘piva’ (the fastest of the four dance types at twice the speed of the bassa danza; by that time, the ‘piva’ (like the ‘quarternaria’) was not favoured as an independent dance in the Italian courts).[12] The variety of metres and steps that might be found in a bassa danza was employed to a greater extent in the other primary Italian court dance, the ballo, which incorporated additional, more decorative movements. Created by specially appointed dance masters (some of whom authored the treatises mentioned above), balli comprised a number of short, distinct sections, each of which presented the metre and steps of one of the aforementioned four Italian dance forms. The frequent contrasts in dance metres and steps and the various ways in which the dancers interacted in balli were key to the dances’ unique choreographies, which ranged from ornamental dances to pieces that conveyed particular dramatic narratives.[13]

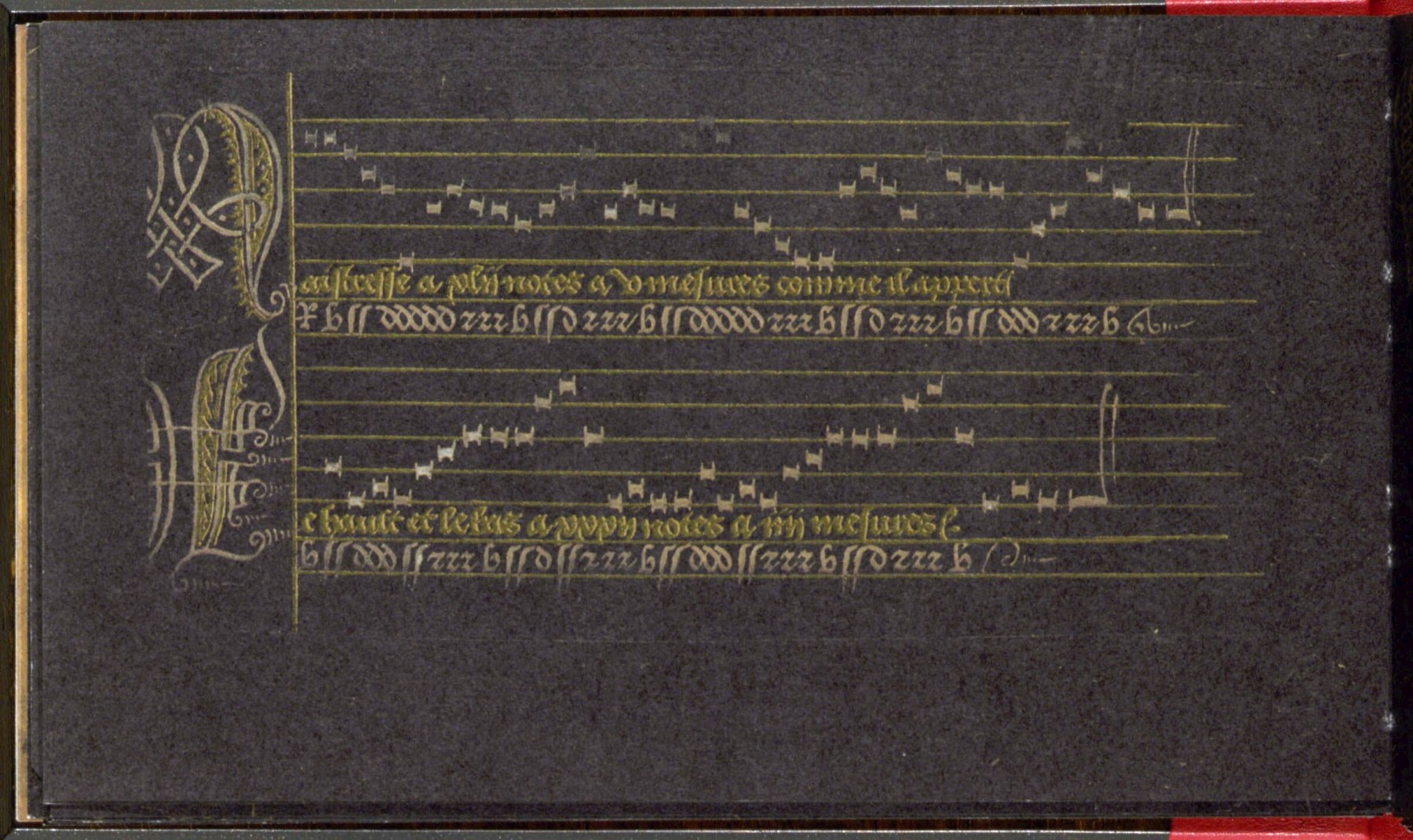

Several of the treatises that describe French/Burgundian and Italian dance practices also present melodies that might be performed alongside particular dances. These melodies were not included for the instrumentalists who would accompany the dances but instead served as aide-mémoires for the dancers, each musical note being equivalent to one dance step. For example, in the basse danse manuscript associated with the Burgundian court of Maximilian’s daughter Margaret, the slow pace of the dances was conveyed by the presentation of the dance tunes in breves, which are annotated with initials that represented the particular dance steps that would be enacted during the duration of each note (» Abb. Maistresse and Le hault et le bas). It is assumed that the instrumentalists who accompanied the dances did so through improvisation around these melodies, which were adapted to fit the length of each dance and were often extracted from the soprano or tenor line of a well-known polyphonic chanson (» Kap. Musicians for civic dancing); some balli were, however, also sung by participants.[14] Whereas the cantus firmi of the basse danses or basse danze were presented in slow notes of equal value (to be adapted by musicians as appropriate), balli melodies usually indicated the frequent changes in rhythm in a dance and reflect the close relationship between the melody and dance steps, both of which were carefully devised by a dance master. As a result, in the aforementioned early dance treatises, descriptions of balli are often accompanied by their particular melodies whereas only three bassa danza tunes are included, perhaps indicating that a melody might be more easily adapted to this less complex dance form.[15] Many of the melodies presented in the dance treatises achieved widespread popularity across Europe, including in settings for keyboard and string instruments for private use: one such tune, ‘La Spagna’ – the only melody to appear in both bassa danza and basse danse sources - was distributed in over 300 different versions.[16]

Dance, Society and Politics

Of the several treatises mentioned above, those by dance masters of Italian courts are particularly illuminating in their justification of the place of dance in elite society. Written by maestri di ballo such as Domenico da Piacenza and his students Antonio Cornazano and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro, these texts convey the importance of dance for learning correct deportment and movement both within dance and in day-to-day interactions, as embodied in the slow, graceful steps of the bassa danza. These dance manuals outline the best qualities of a courtly dancer – male and female - which included the ability to remember the dance steps, to keep time, and to perform in a slow undulating motion with care and grace. Knowledge of these movements was essential to one’s belonging to the right social class and distinguished the elite from the lower classes whose vulgar movements, as Jennifer Nevile describes, ‘exposed to others the baser nature of their souls’.[17] Yet the dance treatises also sought to present these practices on an intellectual level: due to the restraint, order and precision required of dance, it was suggested that these practices had earned a place within the humanist education that was expected of all those in power, who were themselves to be restrained by virtuous aims for the common good.[18]

In addition to the qualities of deportment and self-control that courtly dances were designed to promote, they also communicated particular social hierarchies and groupings, often to the exclusion of others. The first dance of a gathering was usually described in the most detail in contemporary accounts (as demonstrated by those from Worms and Mechelen, above). This was led by the participant of highest social standing, who was frequently identified by name (as was their dance partner) in reports, with features of their dress – another marker of elite status – also being recounted in some detail. Who danced with whom was significant: the partner of the dancer of highest status was also regarded as being of social or political importance, at least in that particular setting.

This strict social hierarchy of dance pairings in Germany was described in detail by Antoine de Lalaing, a courtier of Maximilian’s son Philip, during a visit of the latter to Ulm in 1503. There de LaLaing observed a dance in which Philip, as the gentleman of highest rank, danced with the lady of highest status, subsequent pairings being made likewise, in decreasing order of rank. De Lalaing further noted that if the King danced, he would be surrounded by four dukes, carrying torches if at night, other nobleman being accompanied in a similar fashion by those next in rank.[19] This practice can also be traced in other German cities. In Worms in 1494, as noted earlier, the Count Palatine danced with the Queen, surrounded by eight counts who held torches. In Cologne on 23 June 1505, Maximilian performed the first dance with the Duchess of Lüneburg, four counts carrying torches in front of him and several other princes dancing behind.[20] Further examples of socially significant dance pairings are found in other reports from Maximilian’s and Philip’s travels through the Habsburg territories. In Innsbruck in 1502, for example, de Lalaing recounted how Maximilian led a dance ‘in the German style’ with one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, while Philip himself danced with Bianca Maria (» I. Kap. Jousts and dances for Philip). Furthermore, as described above, during the wedding celebrations in which Maximilian and Bianca Maria participated in Mechelen in 1494, the bride that day was honoured by a dance with Elector Friedrich of Saxony.

Dances were not only shaped by social customs, but also reflected – and enabled – important political interactions. In January 1502, for example, the Venetian ambassador Zaccaria Contarini reported home from Innsbruck of a dance at the royal court from which he had been excluded as a result of political tensions between Maximilian and the Signoria of Venice. Bianca Maria had apparently remarked to the King that, if Contarini were not invited to the dance, she would not attend either.[21] The presence of the ladies of a court, and not only the Queen, was integral to the success of a dance and the political interactions that consequently arose.[22] Women’s conduct and their contact with royal or noble peers was important, not only because their appearance and behaviour reflected on their families, but also due to the possible diplomatic conversations that dances afforded. In February 1504, for example, another Venetian envoy, Francesco Capello, reported that he had spoken to Queen Bianca Maria during a dance about the fact that the current King of Portugal was still without an heir.[23]

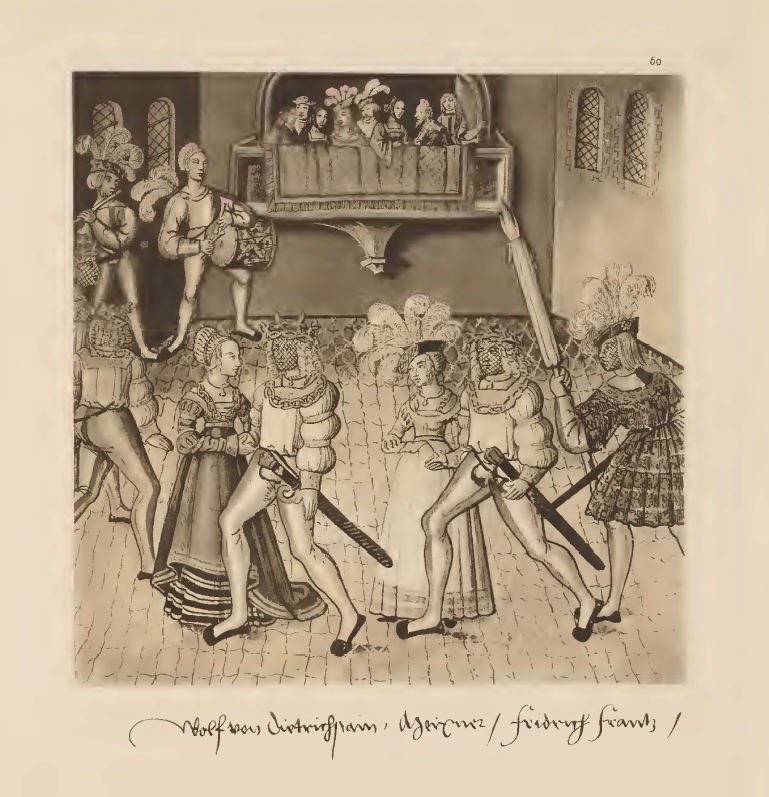

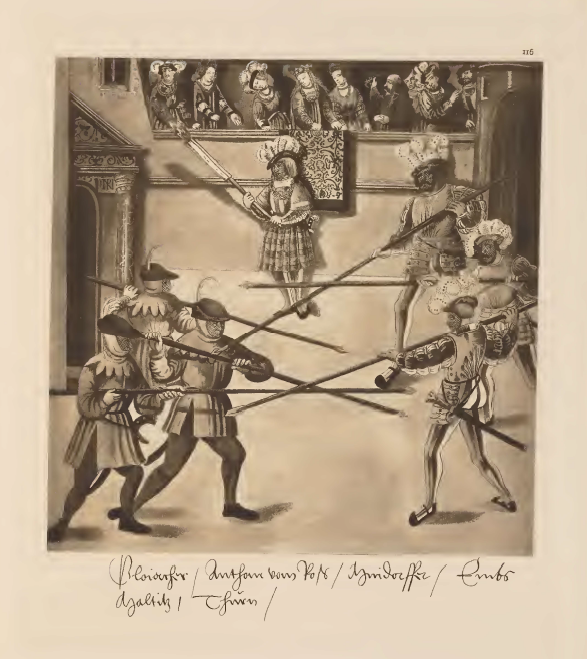

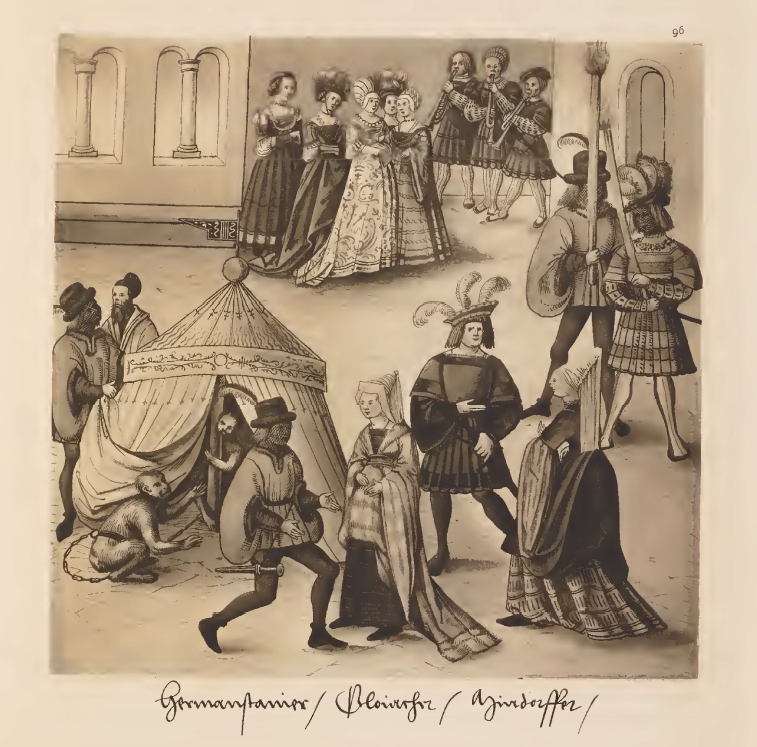

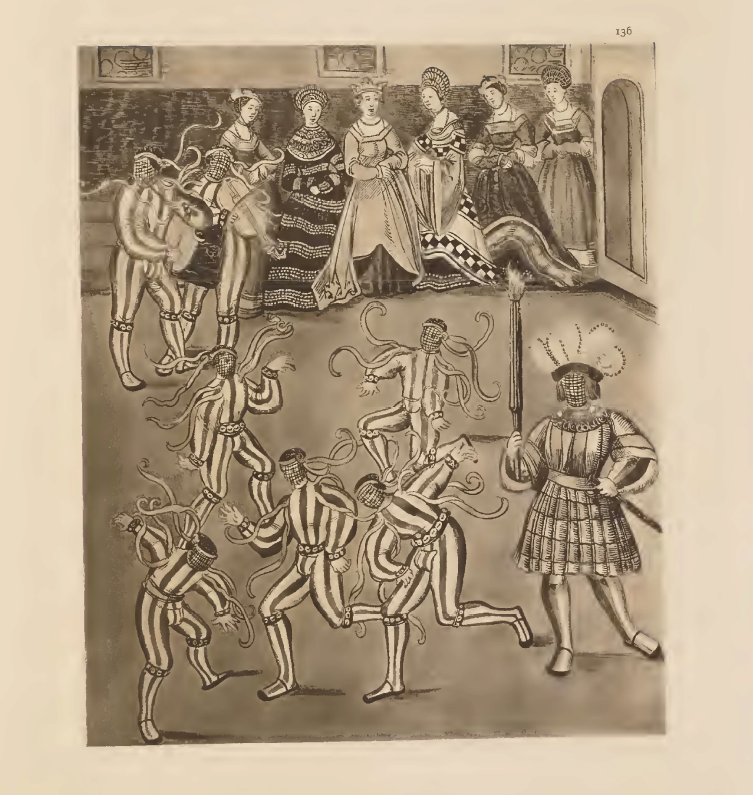

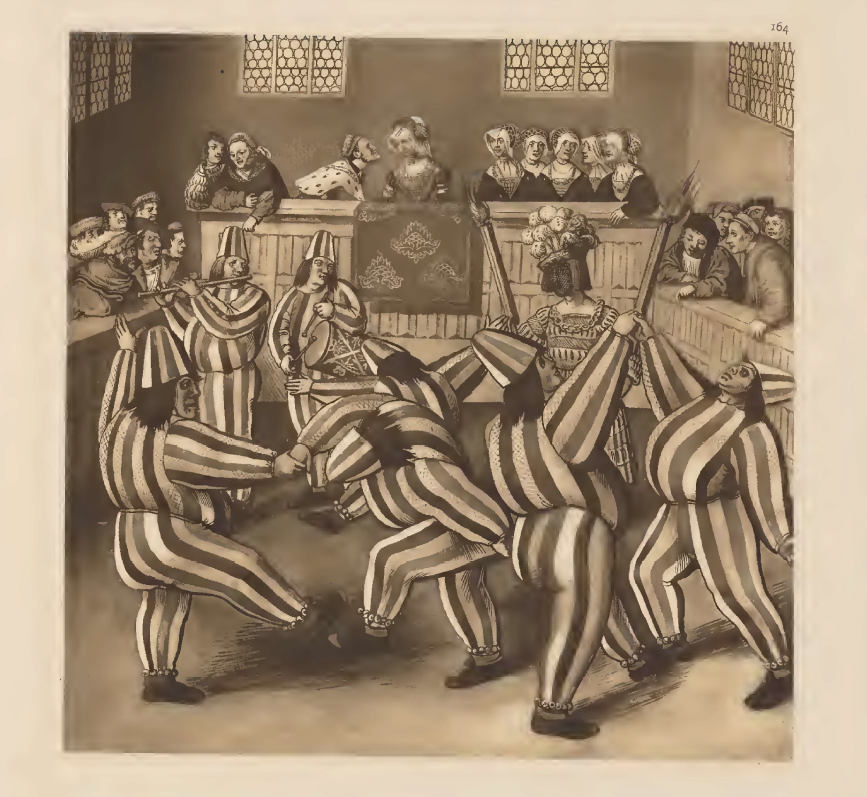

The importance of dance to Maximilian, in the social correctness that it conveyed and the political interactions that it enabled, is not only documented in contemporary accounts of court life, as exemplified above. It is also communicated through the literary works that Maximilian himself commissioned to represent the cultural significance of his reign in an embellished, pictorial form. Freydal, for example, prepared in c.1512-1515, presents Maximilian as the eponymous hero of the piece and traces his quests through 64 courts to reach his first wife, Mary of Burgundy. Although never finished — only five of the planned woodcuts were completed — the surviving miniatures that were to act as sketches for the final prints of the work reflect the importance of dance for the representation of the king. At each court that Freydal visits, he participates in jousts and other forms of combat, followed by a dance, as was typical of courtly ritual of the time.[24]

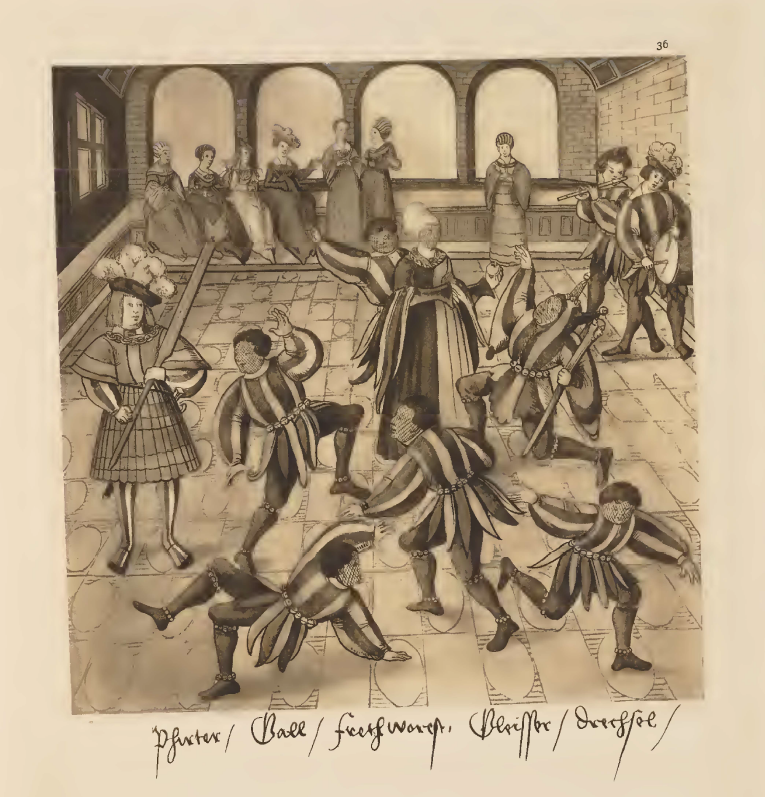

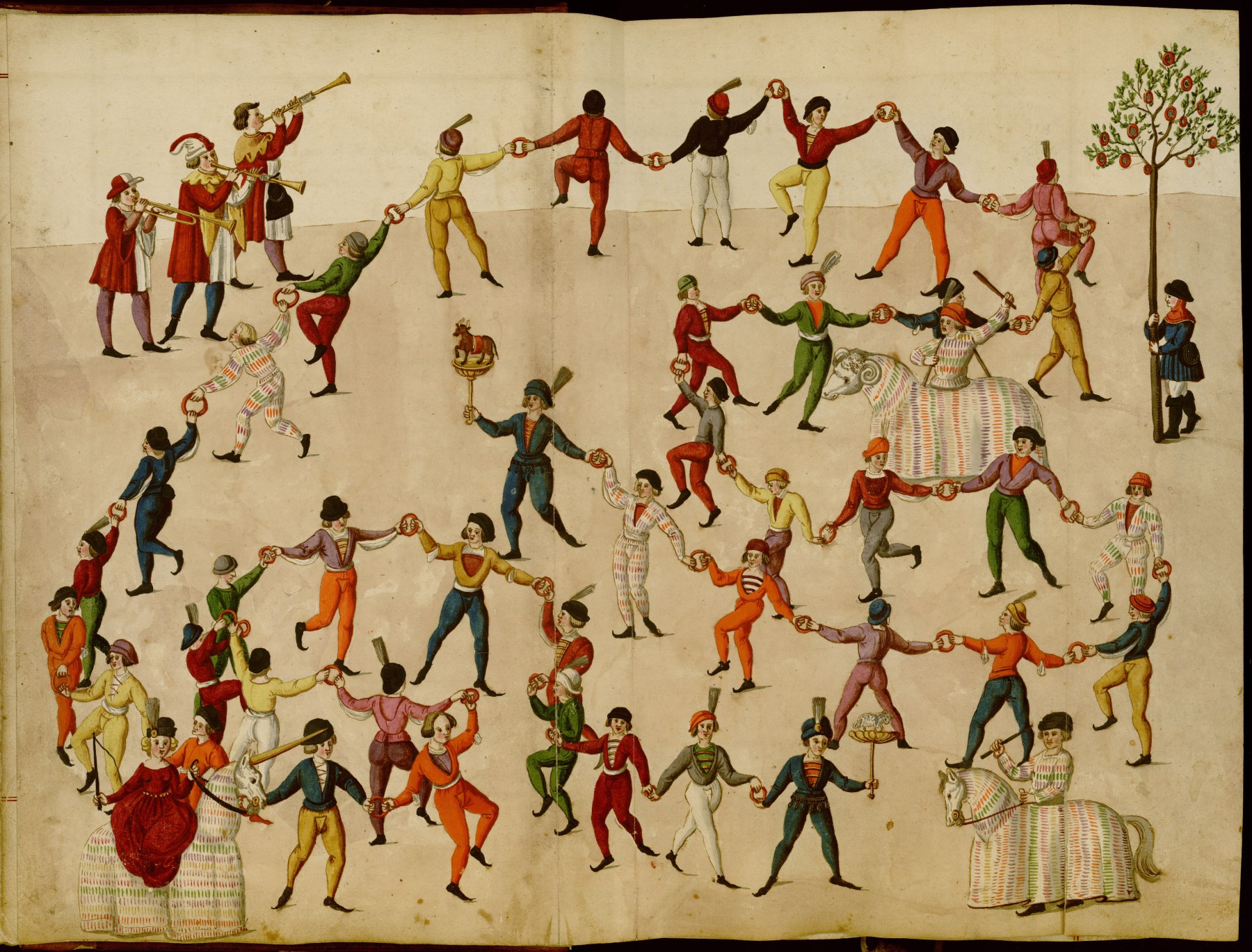

While Freydal might be regarded as representing various dances, including some that might reflect practices described in the aforementioned Burgundian, French and Italian treatises (see, for example, » Abb. A round dance and » Abb. A processional dance), it nevertheless focuses on one aspect of dance that, though rarely described in these dance manuals, was obviously of great importance to Maximilian: the mummery. The contents of the Freydal manuscript confirm that all of the dances depicted were indeed ‘mummeries’, that is a coordinated dance performed in costume. It lists the names (with corrections in the king’s own hand) of all the ladies before whom, and all the gentlemen with whom Freydal is shown as having ‘gerennt, gestochen, gekämpft und gemummt’.[25] The mummeries are variously described with exclamations of wonder (‘wunderbar’, ‘ausbündig’, ‘herlich’), with details of the colour or form of the participants’ costumes (‘in gestallt der vogel’, ‘von hübschen wolriechenden bluemen aller varben, die man kan erdencken’), or an indication of the style of the dances, which range from the more traditional (‘subtil’, ‘holdselig’) to the grotesque and ridiculous (‘seltsam’, ‘frembd’, ‘abentthurig’, ‘lächerlich’, ‘wild’). The miniatures themselves reflect this variety of costumes and dances: in Freydal’s mummeries, the male participants (including the King) are masked, and all male dancers (i.e. not including the King, who is always shown overseeing each performance, holding a torch) appear in the same costume. The dances can largely be distinguished between ‘character’ dances (i.e. those representing particular nations, personalities and communities, such as huntsmen, miners, giants and women, as well as Burgundians, Hungarians, Turks and Venetians), which have more measured steps in keeping with the courtly dances described above; and those regarded as ‘grotesque’, in which the dancers’ costumes are more unusual and their dances involve more comical movements and jumps, distorting the courtly grace usually required of such pastimes.[26] The ladies depicted do not participate in the latter, nor are they usually costumed: they only appear in the typical dances of the court, in appropriate courtly dress.

Although not named as such, several of the more theatrical mummeries depicted in Freydal appear to symbolise dances that are often described as ‘Moriskentanz’ or ‘Morisca’ in contemporary reports. These terms were often used to describe the representation of regions south of Europe in costumed dances, in which the male participants might have their faces painted or covered by a mask or netting, and wear quasi-foreign costumes, adorned with small bells. More generally, however, the ‘Moriskentanz’ was associated with portrayals of strangeness or silliness which could take a number of forms, such as dancing in a circle around a soloist; or the representation of a battle - often between the Christians and the Moors or Turks (see, for example, » Abb. Dancers dressed as soldiers). Otherwise, a ‘Morisca’ might entail a lady of the court judging the best of a group of dancers, who were usually dressed as fools and vied with each other in their grotesque movements

On the relief of the balcony of Maximilian’s Innsbruck residence, Bianca Maria, positioned between Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy, offers an apple as a reward to several such dancers, who are dressed elegantly, but with bells on their ankles and wrists (» Abb. Morisca dancers (relief)). While Freydal identifies the dancers depicted on its pages as nobility or members of the court, professional dancers were also often employed for dances that entailed displays of greater theatricality and more extreme movements not appropriate for those of courtly status. Such professional dancers might perform before or with those of the court — Castiglione advised that when noblemen were involved in such lively performances, these should not take place in public.[27]

Mummerei, Moriskentanz

Although in Freydal Maximilian is not shown as participating in the masked dances himself, as indicated in the account from Mechelen of September 1494 (when the king reportedly danced with a number of his court ‘in disguise and dressed strangely’, » Kap. Dances for the Queen of the Romans), this did not reflect reality.

The king’s involvement in these costumed dances is indicated by the programme for another of his literary commissions, Der Weisskunig (1514-1516, but likewise never finished). Therein, an idealised account of the childhood and youth of the King includes a commentary on the opulent banquets and mummeries of his court (see Abb. Illustration of ‚Die schicklichait‘ for the corresponding illustration), which asserts that Maximilian himself devised the mummeries in which ‘to the delight of his people, and in honour of foreign guests … [he] especially liked to participate’.[28]

Maximilian’s involvement in mummeries is also reflected in Joseph Grünpeck’s Historia Friderici III. et Maximiliani I., in which a chapter on the king’s mummeries (‘De eius spectaculis’) notes how at the weddings of his courtiers, Maximilian frequently danced before them sporting a mask and costume that represented certain nations or communities.[29]

The claims made in both the Weisskunig and the Historia Friderici III. et Maximiliani I are corroborated by several contemporary accounts of entertainments for the King at his Innsbruck residence, many of which appear to have taken place amidst celebrations for Shrovetide. On 12 January 1497, for example, the Ferrarese envoy Pandolfo Collenuccio described a masked dance in which the King participated, and on 24 January 1502 the Venetian envoy Marino Sanuto reported of dances that occurred as part of a joust (see also » I. Kap. Jousts and dances for Philip), in which the King was accompanied by several wild men playing on brass instruments.[30] Yet the costumed dances of the court were not restricted to the privacy of Maximilian’s residence at Innsbruck, and instead occurred at various locations across the Habsburg territories from the earliest years of his reign as King of the Romans. In April 1486, for example, Maximilian’s coronation was celebrated in Cologne with a mummery accompanied by pipe and drum, which began with a ‘Morisca’ in the French style performed by professional dancers dressed as a fool, a lover, an Indian maiden and three moors. The King himself then participated in another French dance, at first disguised by a silver mask with a long beak.[31]

These costumed dances seem to have been performed in accordance with many of the dance practices outlined in treatises of the time: the lady who was paired with the King for the aforementioned dance in Cologne was given particular mention in one eyewitness account due to her knowledge of appropriate Italian dances. On another occasion, in Augsburg in November 1507, Maximilian, who was reportedly dressed in the French style, attended a dance at the town hall which included two basse danses, the first involving the king and two of his companions and the second for the king alone.[32] In both Cologne in 1486 and Augsburg in 1507, dances in the German style were also performed, yet before these commenced in Cologne, the King, now unmasked, began another dance, which would have differed from the aforementioned French and Italian courtly practices through its association with the common folk and therefore with simplicity and frivolity. This was the ‘branle’, in which dancers were arranged in a circle or line and performed movements that included jumps and kicks.[33] Antonius de Arena’s more informal dance manual Ad suos compagnones studiantes (Avignon, ?1519) includes a number of insights into such dances: ‘When our country folk dance they throw themselves about and do not even observe the beat. … They do the branles boisterously, country style, and everyone thinks himself a past master of dancing. They keep this up until the taborer is exhausted.’[34]

Interest of the social elite in practices of the common folk was not unusual. In a mummery held during a meeting of the Swabian League in Augsburg in 1504, according to Hans Ungelter, the delegate for the city of Esslingen, a group of around 100 people, including Maximilian, participated in a costumed peasants’ dance at the dance hall. They then removed their peasants’ clothes to reveal more opulent attire before they commenced a dance in the Italian style, the King himself dressed in gold. This transformation highlighted the distinction between the usual courtly attire (and dancing) of those present and the social ‘other’ that they here sought to represent. The ‘peasants’ dance’ that Maximilian performed on this occasion is not described in detail by Ungelter, but his reference to the musical accompaniment of the dances on lute and with songs does raise the possibility that this was a form of ‘branle’ - a style of dancing that was commonly accompanied by the singing of participants.[35]

Urban Courtly Dance

The performance of courtly dances in civic environments was not only a consequence of the travels of royalty and nobility through the Habsburg territories; it was a reflection of the aspirations, education and customs of the German urban elite who sought to adopt courtly behaviour wherever possible, including in dance. The importance of such dances to the cities’ upper classes is indicated in the correspondence of the Nuremberg councillor and humanist, Willibald Pirckheimer, whose circle included the renowned theologian and music theorist Johannes Cochlaeus, the astrologer and physician Lorenz Beheim, and the celebrated artist Albrecht Dürer. In 1515, Cochlaeus had accompanied Pirckheimer’s three nephews on their formative travels to Italy, from where he sent Pirckheimer regular updates on the boys’ progress in their studies. It is from this correspondence that we learn of the Pirckheimers’ interests in Italian dance. In a letter of 17 January 1517, Cochlaeus wrote from Bologna that he had not yet been able to procure details of such dances, as previously requested by Pirckheimer’s daughters back in Nuremberg. In a subsequent letter, of 7 March 1517, Cochlaeus was finally able to fulfil their wishes, enclosing the choreography, written by an unidentified acquaintance, for eight dances that appear in contemporary Italian dance treatises: the famous bassa danza La spagna and seven ‘balli’, six of which have been identified by Ingrid Brainard as dances created by Domenico da Piacenza (» Kap. Dance, Society and Politics). Brainard and Christian Meyer have both commented on the instructions sent by Cochlaeus, which in their simplicity are unlike the complex professional dance treatises prepared by Piacenza and his students - perhaps a result of the directions being written down during or following a dance performance or lesson. Moreover, their lack of detail indicates that Pirckheimer’s daughters back in Nuremberg were already sufficiently well-versed in Italian dance to be able to understand and perform these ‘new’ dances based on the rudimentary instructions conveyed with Cochlaeus’s letter.[36]

Letters to Pirckheimer from other friends present further examples of the interest of Nuremberg’s elite in foreign, courtly dance styles. On 13 October 1506, Albrecht Dürer reported from Venice of his failure to learn dancing in the local style, and in a letter of 21 February 1507, Lorenz Beheim (writing from Bamberg) referred to the public practice of such Italian dances in Nuremberg’s town hall: ‘I have learned from certain people, that you have had fine festivities this Lent, that you have brought here strange spectacles, and, of course, that you have danced in the Italian manner.’[37]

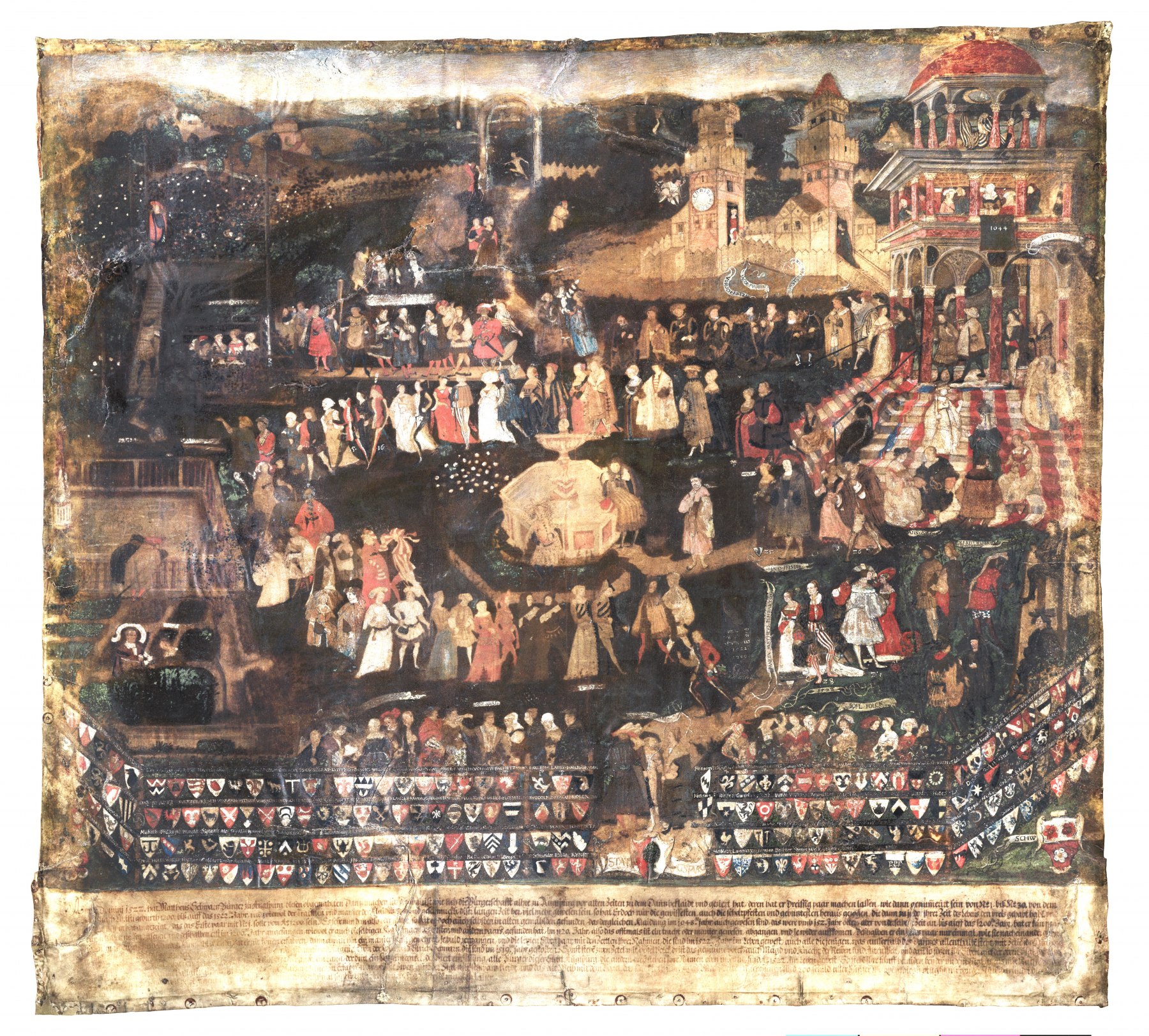

The dance practices to which Pirckheimer and his friends refer were a much sought-after accomplishment for many of those living in the cities of the Empire. These dances allowed the urban elite to adopt the deportment and etiquette appropriate to courtly society, while also enabling the presentation of the participants’ differing social status. Abb. Processional dance at Augsburg’s town hall depicts a dance in the Augsburg town hall c.1500, which highlights the representational function of the processional dances performed there in accordance with courtly customs: the dancers’ names identify each individual as belonging to the elite of the city. Their affluence is indicated by their opulent clothing, the importance of which is affirmed by the piece’s title: ‘Nach cristy gepurt 1500 iar was dise claidung zu Augspurg das ist war’ (‘In A.D. 1500, this was the clothing in Augsburg, as is the truth.’). Georg Habich suggests that Queen Bianca Maria herself can be identified to the left of the picture: she and Maximilian were both present in Augsburg that year for the Reichstag.[38]

Dance Music in the Cities

It was not only the steps of courtly dance that were well-known to the urban elite, but also the repertoire that was associated with these dances. On 8 June 1506, in another letter to Pirckheimer, Behaim, a keen lutenist, remarked on a number of bassadanze that he had in his private music collection, including ‘two bassadanze by Johann Maria … Then the bassadanza by Augustino Trombone, who is in the service of the King of the Romans, and it is quite good and easy. Then there’s another simple bassadanza that can be played on the organ.’[39] Keith Polk and Christian Meyer suggest that ‘Johann Maria’ was a well-known German lutenist then working in Italy, and identify ‘Augustino Trombone’ as the multi-talented lutenist, cornettist and trombonist Augustin Schubinger, a former Stadtpfeifer of Augsburg.[40] A few weeks later, on 29 June, Behaim wrote again to his friend informing him that ‘I am sending you some other bassadanze that I have played; if they please you, copy them and send them back. They are written for 13 strings but you can easily arrange them for 11 strings.’[41] Many dance melodies of the time achieved widespread popularity and were adapted for private performance on instruments such as keyboard and lute. Crawford Young suggests that use of the term ‘bassadanza’ in lute manuscripts of the time refers specifically to settings of the melody known as ‘La Spagna’, i.e. this was the bassadanza melody known to everyone.[42]

This familiarity of the German urban elite with popular dance melodies and the subsequent adaptation of these melodies for private musical practice are also evidenced in music anthologies of the time. For example, the song book assembled by the Nuremberg humanist and patrician Hartmann Schedel completed shortly after his studies in Padua (1463-66), contains, amongst other repertoire, two ‘Carmina ytalica utilia p[ro] coreis’ (‘Italian pieces useful for dancing’), which have in fact been identified as dance tunes of Burgundian origin.[43] Some years later in Basel, the organist Hans Kotter and his colleagues Hans Buchner and Johann Weck compiled a collection of keyboard pieces for Kotter’s pupil Bonifacius Amerbach (whom he taught from c. 1510), which included several settings of dance tenors, four based on ‘La Spagna’. Weck’s setting of the melody (‘Spanyöler Tancz’) is followed by a ‘Hopper dancz’ in halved-note values, similar to the after-dance of a bassa danza or basse danse. Daniel Heartz considers the unusual, syncopated rhythm of the Spagna melody in Weck’s ‘Tancz’ to be a distinctive feature of German adaptations of the later basse danse form, identifying this rhythmic peculiarity in three other dance settings by Weck and Buchner in the Amerbach manuscript (‘Tanz der Schwarz Knab’, ‘Tanzmass Benzenhauer’ and ‘Ein ander Tanz’).

The latter three dances all also appear in Hans Judenkünig’s instruction books for lute printed in Vienna in c.1519 and 1523, each with its own after-dance. In Judenkünig’s settings, the three dance pairs are all given the title ‘Hoftanz’ (‘court dance’). Moreover, both Otto Gombosi and Daniel Heartz have connected this repertoire with the performance of such ‘court dances’ in the German cities. In another lute tablature of the early sixteenth century, D-Mbs Mus. Ms. 1512, a setting of the ‘ander Tanz’ appears with the title ‘Der annder statpfeifer danntz’, therefore associating the melody with its performance for dance in a civic setting. This suggestion is corroborated by pictorial evidence, as identified by Heartz.[44] In Narziss Renner’s painting of a garden dance in Augsburg, dated 1522 (» Abb. Narziss Renner, Gartenfest (1522) and » Abb. Musicians at a civic garden party), behind a procession of patricians whose costumes reflect the transition from the Middle Ages to the year of the painting, there stands a small group of musicians, whose attire and instruments also reflect the chronology represented by the picture.[45] At the centre of this group are three Stadtpfeifer above whose heads a tenor melody can be seen, which Heartz has identified as a setting of ‘Der ander Tanz’ that closely resembles the version in Judenkünig’s publication of 1523. That this melody is identified as both a ‘Hoftanz’ and a ‘Statpfeifer danntz’ reflects the free movement of such dance repertoire between court and urban society.

The shared dance repertoire of city and court is further suggested by another musical source associated with Augsburg, which also alludes to the role of civic and court instrumentalists in the dissemination of dance music: the so-called Augsburg Song Book. This manuscript, which was assembled between 1499 and 1513, contains (along with several vocal pieces) a number of instrumental dances whose Italian origins are reflected in their titles (e.g. ‘La Gambetta: Mantuanner dantz’). Although the early history of the manuscript is unclear – Rainer Birkendorf links its compilation with the Imperial chapel itself — connections with the musicians of Augsburg are in fact evident on one of its pages. As Keith Polk has suggested, a scribbled and obscure note concerning one of the city’s Stadtpfeifer, Jakob Hurlacher, on a page that contains a setting of Dies es laetitae, may possibly indicate his or his colleagues’ role in the transmission of the ‘Mantuan’ or other Italian dances to Augsburg (» Abb. Jakob Hurlacher in the Augsburg Songbook). German instrumentalists were in great favour in Italian cities at that time, and both the aforementioned Augustin Schubinger and his brother Ulrich — predecessors of Hurlacher in the Augsburg Stadtpfeifer ensemble — were employed in Mantua, Ulrich certainly visiting Augsburg from that city at the time that the song book was being compiled.[46]

Dance, urban society and civic space

Overseeing the various kinds of dances that might occur within a city was each municipal council, whose strict supervision of all aspects of urban life was designed to ensure that everything was conducted with propriety and decency. Public dances held in the open, for example, were often subject to council restrictions as a result of the greater freedom – and possibly noise – that they entailed.[47] In Schwäbisch Gmünd these dances were banned in their entirety, although whether the citizens conformed to this ruling is questionable – the celebration of dances ‘uff der gassen’ was repeatedly forbidden.[48]

Civic dances were in themselves social markers: only particular communities were permitted to dance together, to the exclusion of others. Dancing occurred in various locations across a city, including on the streets and squares, in the homes of rich patricians and also in public buildings such as at the town hall. These venues were not only suited to the participants’ social-standing but sometimes contained rooms that had been designed or adapted with particular dances in mind. For example, many cities boasted specially built, and richly decorated, dance halls, which served the processional dances of the social elite through their great length and by having balconies from where musicians could observe the dancers and provide appropriate music. The buildings in which dance halls were constructed often served multiple purposes, also accommodating the city’s governmental, legal and economic activities.[49]

Participation in events at the cities’ dance halls was generally restricted to the elite and required prior permission from the civic council. In Nuremberg in 1521, for example, the social group regarded as having the power to vote in the city was described as comprising ‘those families who used to dance in the Rathaus in the olden days, and who still dance there’.[50] The town hall was the customary venue for the dances of Nuremberg’s elite, and so, in records of the city’s council we find numerous references to permissions granted for the use of the hall for such occasions. In 1491, for example, the council noted that the young patrician Wolf Haller von Hallerstein had been permitted the use of the rooms of the town hall together with the official musicians of the city for his wedding to Ursula, daughter of the printer Anton Koberger.[51]

The restriction of particular dances and their venues to certain members of the community was not defined exclusively by the participants’ social-standing but also by their religion. In many cities, such as Frankfurt am Main, Augsburg, Rothenburg ob der Tauber and Ulm, the Jewish population had at that time their own dance hall, entrance to which was not permitted for the Christian community.[52] As Walter Salmen notes, in 1483, several Nuremberg patricians, including the aforementioned Martin Behaim, were jailed for participating in festivities at the Jewish dance hall.[53]

Musicians for civic dancing

The musicians who might provide the accompaniment for courtly and civic dancing, whether at Maximilian’s residence at Innsbruck or in the squares and dance halls of the Empire’s cities, varied according to a number of factors, including local finances and social customs and constraints. The influence of the latter on musical performances for dancing was also reflected in the decrees of local town councils, which provide useful indications of the musicians – amateur and professional – who might be involved in these gatherings. For example, in Strasbourg in 1533 the council there declared that ‘Die rundtaenze seien zugelassen doch nicht schaendliche Lieder daran zu singen’[54] (The round dances are permitted yet not the singing of shameful songs for these). The singing of dancers as they performed in a round was common practice – the Lochamer Liederbuch’s ‘Ich spring an disem ringe’ (I leap in this round dance) exemplifies one such dance song.[55] Sung accompaniments were also provided for, it would seem, dances for royalty and nobility: as described above, in Augsburg in 1504 a ‘peasants’ dance’ involving the King was accompanied by both instrumental music and singing (» Kap. Mummerei, Moriskentanz).

Yet not only dance songs were subject to council constraints; dances accompanied by instruments were affected by similar restrictions. In Basel in 1492, for example, the council there issued a decree forbidding ‘die tantz, so uff offener gassen mit pfiffen, lutenslahen und andern seitenspilen bisshar gepflegen sind.’[56] (the dances that have until now been pursued on the open streets, with playing on pipes, lutes and with other forms of music). As Nicole Schwindt has suggested, the term ‘Saitenspiel’ appears to have been common parlance for all kinds of instrumental music, and not only that of stringed instruments.[57] The potential variety of instruments that might accompany civic and courtly dances is indicated in several Hochzeitsordnungen of the time. These documents were created by city councils to regulate the size, nature and conduct of wedding celebrations in accordance with the wedding party’s social status. Restrictions were applied not only to the number of wedding guests, their clothing and dining arrangements, but also to the type of musicians they were permitted to employ. A Hochzeitsordnung created in Frankfurt am Main in 1489, for example, explained that, dependent on the status of the bridegroom, the musicians that might be appointed for a wedding could range from visiting courtly or civic brass and wind instrumentalists (‘trumpter und pfiffer’, paid two guilders each) to resident wind instrumentalists and visiting lutenists (paid one guilder) and resident lutenists, fiddlers, drummers and bagpipers (paid half a guilder).[58]

Within the cities, use of the Stadtpfeifer for dances seems to have been primarily reserved for citizens of higher social status. During Maximilian’s reign, in the German cities these ensembles had as few as two (in the smallest towns) and as many as five (in cities such as Nuremberg and Cologne) members, who would typically play together on slide brass instruments, shawm and bombard, as well as on other wind instruments, where possible.[59] Though no musical sources can be directly linked with these ensembles due to their practice of playing from memory,[60] scholars such as Keith Polk have nevertheless determined that for dances during the late fifteenth century, musicians would have improvised upon a given tune played in slow note values (as set out in the dance treatises described above), around which the outer parts would weave one or more counterpoints for the duration of a dance. While at first, this melody was usually placed in the tenor part (having often been extracted from the tenor voice of a chanson), after 1500 the soprano line began to dominate and pieces were often constructed from repetitions of short sections rather than being through-composed (as exemplified by the music for the later basse danse and its German variant, the Hoftanz).[61] As Polk remarks, the dance pieces contained in the Augsburg Song Book, such as the aforementioned ‘Mantuanner dantz’, represent such later instrumental practices, in their repetitive phrases and soprano-dominated texture.[62]

Amongst the most notable events in the civic year were the celebrations for Shrovetide, which drew on civic dancing and music in all their forms. The Nuremberg carnival held annually between 1449 and 1539 is particularly well-documented in this respect and involved processions, dances and pageants in all parts of the city. As in the mummeries at court, costumes were key to these Fastnacht celebrations, the local name for the carnival – ‘Schembartlauf’ (‘Schem’ being the Old High German for ‘mask’[63]) – reflecting the importance of costume for civic festivities too. Records of the Nuremberg council include reference to costumes of certain ‘junge Gesellen’ not only for these Fastnacht celebrations but also for other ‘Moriskentänze’ during the year,[64] and in 1491, it was Maximilian who appeared in costume for Shrovetide, in Italian and Dutch dances that were performed at the town hall.[65] The Nuremberg carnival traditionally centred around the round dance of the butchers, who were also allowed the use of the Stadtpfeifer for their dance in the open (» Abb. The dance of the Nuremberg butchers); council records confirm the continuing support for this honour over many years.[66]

Instruments for courtly and civic dancing

The musical resources of the cities were often noticeably enhanced by the visits of external musicians who regularly accompanied their royal and noble patrons upon their travels across the Empire for major political gatherings such as the Imperial diets. Though eye-witness accounts of their performances for dances in the cities often lack detail, they are nevertheless illuminating in the information they provide about the additional instruments that this court presence offered. References to the playing of ‘trumpeters’, for example, suggest a notable addition to civic resources, as at this time no German city possessed a trumpeter corps to match that of a royal or noble court. In Augsburg in 1496, Maximilian and his son Philip were reported to have danced around a fire with ‘some 10,000 people’, accompanied by ‘all the trumpeters’ there present.[67] Furthermore, at the Reichstag in Cologne in 1505, the series of dances that took place on 23 June (the last of which was described as ‘eynen Ronden dantz’) was accompanied by the princes’ trumpeters, of which there were around 34, 8 kettledrums, and two groups of Stadtpfeifer, from Cologne and Aachen.[68]

The presence of different groups of instrumentalists for one dance, as described in Cologne in 1505, was not unusual. In Donauwörth in 1500, for example, it was reported that, for a dance in celebration of the birth of the future Emperor Charles: ‘…hett K[ayserliche] M[ayestät] sein Trummeter, Kessel oder groz Baugen auf ain ortt verordnet, auf den andern die Zwerch pfeyffen vnd feld baugken, auf den dritten zingken vnd ander pfeyffer…’[69] (…His Imperial Majesty had ordered his trumpeter, kettle or large drum to one place, at the second, fifes and tabors, and at the third, cornetts and other pipers…). And at the wedding of Margrave Kasimir of Brandenburg and Susanna of Bavaria in Augsburg in 1518, trumpets again accompanied the dancing that evening with other instrumentalists: ‘alldo was zwayerley melody von zwayen Partheyen Baycken trummeter, die gar herrlich in ainander erhallen, mitsampt andern saitenspilen.’[70] (there were two types of melody from two parties of drummers and trumpeters, who sounded together quite magnificently, along with other music). Rainer Gstrein suggests that, while the term ‘Trummeter’ might refer to all kinds of loud instruments, the possibility remains that trumpeters may have played for the initial courtly dances – those with long, drawn-out steps —with other instrumentalists taking over for subsequent dances of faster tempo.[71]

Freydal represents many such instruments accompanying dances purportedly experienced by the King upon his quest to Mary of Burgundy:

However, there is very little documentary evidence of such performances taking place at the royal court. According to Anthoine de Lalaing, trumpets and drums played for dances during the visit of Philip of Burgundy in 1503 (» I. Kap. Jousts and dances for Philip), yet references to performances on other instruments are lacking, with one notable exception. The financial records of Maximilian’s court include a handful of payments to a piper and drummer for dances for Shrovetide between 1491 and 1493, and a further payment to them for various dances in 1496 (» Kap. Musicians for dance music). It is this combination of pipe and drum that is most frequently represented in Freydal, played by either a single musician or an ensemble of two (» Abb. Performance for dancing on pie and drum by two musicians; » Abb. Performance for Morisca dancing on pipe and drum by two musicians; » Abb. Performance for dancing on pipe and drum by one musician). While both Freydal and the financial records of the court link this combination of instruments with performances for mummeries (see also the account of the mummery in Cologne, 1486 » Kap. Mummerei, Moriskentanz), the ensemble seems to have achieved widespread popularity for all kinds of dances in both court and civic circles. In his Musica getutscht of 1511, Sebastian Virdung commented on the frequent use of pipe and drum for dances and weddings in France and the Netherlands.[72] Furthermore, it is these instruments that are shown playing for a courtly dance in Maximilian’s Fischereibuch (» Abb. A courtly dance accompanied by pipe and drum) and are also described as having performed for dances in Donauwörth in 1500 (see above).[73]

Though in the cities the Stadtpfeifer were regarded as possessing the highest status amongst resident musicians, there is also evidence of the employment of pipe and drum there for dancing. In the picture of the Augsburg patricians’ dance of 1500, for example (» Abb. Processional dance at Augsburg’s town hall), in the balcony up on high, the three Stadtpfeifer can be seen having a break from their playing, while a piper and drummer continue. In Nuremberg, a piper and drummer duo was employed throughout Maximilian’s reign, in addition to the resident Stadtpfeifer ensemble; a fresco that once adorned the walls of the city’s town hall shows the Stadtpfeifer playing, while in this case, it is the piper and drummer who rest (» Abb. The Nuremberg Stadtpfeifer ensemble, with a piper and a drummer).[74] The Schembartbücher that commemorate the Nuremberg carnival refer to the participation of the piper and drummer in the annual Shrovetide festivities, and namely for a dance in the streets that contained jumps and leaps and was performed by a group of citizens in vibrant and matching costumes.[75] Scholars such as Hoffmann-Axthelm and Gstrein suggest that the drum acted as a drone instrument beneath the pipe which created more elaborate music above. Such practices can be inferred from a later treatise, Thoinot Arbeau’s Orchesographie (1588), which considers the different roles of pipe and drum in the accompaniment of dance, the music for the fife being ‘composed to the player’s fancy’, while the drum, which was to mark the dancers’ steps, ‘blends [with other instruments], adding charm and serving as a bass and diapason to all harmonies.’[76]

Conclusions

Though the civic and court communities of Maximilian I’s Holy Roman Empire were differentiated by their distinct social and political status as well as the architectural spaces that they inhabited, the dances performed by urban and court society shared common steps and repertoire, as well as similar cultural aspirations. The dances of both the urban and courtly elite had their foundations in the dance steps and repertoire of the Burgundian, French and Italian courts, which circulated widely across Europe and promoted the poise that was appropriate to all forms of genteel behaviour. While the elegant practices of the social elite excluded those of lesser status and grace, the upper echelons nevertheless expressed an interest in the carefree movements of the common folk, which they would sometimes incorporate into costumed dances, especially during festivities for Shrovetide. The core dance repertoire of the civic and court elite therefore encompassed not only a range of national dance styles, but also movements that spanned from the refinement required of polite society to the vulgarity associated with the common folk. It was this shared dance repertoire that was visible to all when the King himself visited his cities, patrician and prince dancing together in a public display that, despite their physical interactions through dance, continued to convey any social hierarchies or political difference.

[1] Unterholzner 2015, 51; Wiesflecker 1971, 372-9.

[2] Annotations on the diary of Reinhart Noltz, Mayor of Worms, in: Boos 1893, 379. Translations of this and the following citations by Helen Coffey, unless stated otherwise.

[3] Neudecker and Preller 1851, 231.

[4] Hegel 1874, 732.

[5] Letter from Barbara Crivelli Stampi to Anna Maria Sforza, Duchess of Ferrara, 24 January 1494. Full transcript in Aigner 2005, 76-7.

[6] Guglielmo di Ebreo claimed that anyone who had studied the exercises in his treatise (1463) would be able to master the dance of any nation. See Nevile 2008, 13.

[7] See note 5.

[8] Amongst the earliest and most significant treatises of the fifteenth century are those prepared by dance masters of the Italian courts, which include Domenico da Piacenza’s De arte saltandi e choreas ducendii (c.1440-50), Antonio Cornazano’s Libro dell’arte del danzare (first version (now lost), 1455; second version, 1465) and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro’s De Pratica Seu Arte Tripudii (1463). French and Burgundian dance practices and repertoire are conveyed in the basse danse manuscript associated with the Burgundian court of Maximilian’s daughter Margaret (now Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique MS 9085, c.1470-1501) and the related printed treatise L’Art et Instruction de Bien Dancer (published in Paris by Michel Toulouze, in or before 1496). For these, and later dance treatises, see Nevile 2004 and Heartz 1958-1963.

[9] See Heartz 1958-1963 and Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[10] See Heartz 1966; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[11] Heartz 1958-1963, 290; Nevile 2004, 21.

[12] Sparti 1986, 347; Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[13] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7. See also Sparti 1986 and Brainard 2001.

[14] Gombosi 1941, 294, 299-300; Heartz 1958-1963; Strohm 1993, 348, 553.

[15] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7.

[16] Heartz 1966, 19. A significant use of the melody occurred in the Missa La Spagna by Henricus Isaac: see Mücke-Wiesenfeldt 2012.

[17] Nevile 2004, 2.

[18] Gombosi 1941, 298; Nevile 2004, 1-3.

[19] Gachard 1876, 305-306; for a German translation of the text, see Jungmann 2002, 65-66.

[20] Fucker 1505 (not paginated), quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[21] RI XIV,4,1 n. 15882, in: Regesta Imperii Online: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1502-01-09_1_0_14_4_0_49_15882

[22] Kelber 2018, 124-7.

[23] Forthcoming in Regesta Imperii Online.

[24] Franke and Welzel 2013, 34-40.

[25] Leitner 1880-1882, IV.

[26] Leitner 1880-1882, LIII.

[27] Locke 2015, 115, 117-125; Franke and Welzel 2013; Welker 2013; Vignau-Wilberg 1999, 76.

[28] ‘zu frewden seinem volk und zu eren der frembden geest … ist [er] in sonderhait geren in der mumerey gegangen’. See Schultz 1888, 82-4; also Franke and Welzel 2013, 35 and Kelber 2019, 59.

[29] ‘At in aulicorum suorum nupciis conseuit frequenter conmutatis vestibus in gencium aliquarum ritum personatus coram populo saltare. Qua humanitate atque liberalitate sibi multum fauoris tum principum tum populi precipue soeminarum conciliauit.’ See Chmel 1838, 91 for a transcript of the original text; a German translation is presented in Ilgen 1891, 57-8 and quoted in Gstrein 1987, 94.

[30] Barozzi 1880, 216.

[31] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 123-4.

[32] Letter from Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara to Maximilian’s daughter Margaret, 22 November 1507, quoted in Kooperberg 1908, 363.

[33] Heartz and Rader 2001c; Sutton et al. 2001.

[34] Translation from Guthrie and Zorzi 1986, 19.

[35] See Kelber 2019, 66-67; also Schwindt 2018, 83.

[36] Meyer 1981, 64-66, Brainard 1984, Wetzel 1990; also Brinzing 1998, 133-134.

[37] Reicke and Reimann 1940, 439-440 and 496. An English translation of Dürer’s letter is in Fry 1913, 26; Beheim’s letter is translated into French in Meyer 1981, 63.

[38] See Habich 1911, 234; also Kelber 2019, 252.

[39] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 46. Also cited in » H. Kap. Eine süddeutsche Humanistenkorrespondenz (Markus Grassl), with further explanation.

[40] See Meyer 1981, 63-64, Polk 1992, 141-2.

[41] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 47.

[42] Young 2013, 46.

[43] See Heartz 1966, 19-20 and Polk 1992, 135, 139.

[44] Heartz 1966, 20-26.

[45] Habich 1911, 220. For another pictorial document of civic dancing and musicians, see » E. Kap. Musik im Dienst, und » Abb. Patrizierfest.

[46] See Polk 1992, 141; Brinzing 1998, 139-140; Kelber 2018, 136-8. Further on the MS, see » H. Kap. Schubinger und das Augsburger Liederbuch (Markus Grassl).

[47] For an overview of the restrictions see Brunner 1987.

[48] Stiefel 1949, 135.

[49] Brunner 1987, 58-63; Salmen 2001, 165.

[51] Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60a (Ratsverlässe), Nr.259, fol. 5v.

[52] Brunner 1987, 58.

[53] Salmen 1992, 23; see also Salmen 1995.

[54] Vogeleis 1979, 228.

[55] Salmen 2001, 174.

[56] Ernst 1945, 203.

[57] Schwindt 2018, 83-4.

[58] Gstrein 1987, 81.

[59] Polk 1992, 109. See also » E. Musiker in der Stadt (Reinhard Strohm).

[60] On surviving written sources related to Stadtpfeifer and their music (Maastricht fragment and others), see also Strohm 1992; Brown and Polk 2001, 127.

[61] Polk 2003, 98-104; see also, Heartz 1958-1963, 313-316; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[63] Schünemann 1938, 53.

[64] See Welker 2013, 76.

[65] ‘so ließ die künigliche majestat derselben nacht ein tantz auf dem rathaus halten und mancherlei tentz auf welsche und niderlendische art üben und spil treiben, darin auch der kunig persönlich in einem schempart was.’ in: Hegel 1874, 732.

[66] Several references in the records of Nuremberg’s council refer to permission granted for use of the Stadtpfeifer, Stadtknechte and Schützen for the butchers’ annual Shrovetide dance. See, for example, Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60b (Ratsbücher), Nr. 4, fol. 156r (1486), fol. 228v (1487), Nr. 5, fol. 4v (1488) and Nr. 6, fol. 2r (1493). For the development of and sources for the Schembartlauf, see Sumberg 1941 and Roller 1965.

[67] ‘Der ro. kinig und sein sun Philipps sind zü pfingsten 1496 hie gewessen. da hat man 10 füder holtz auff den Fronhoff gefiert, und nach ave Maria zeit ain himelsfeur gehebt, und hertzog Philipp und sein adel haben 3 mall um das feur dantzt, und sind da all trumether gewessen, und hand da ob 10000 menschen dantzt.’ in: Roth 1894, 71-72.

[68] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[69] Donauwörth Stadtarchiv, Johann Knebel, Stadtchronik (unpublished), fo.206v (cited in correspondence from Donauwörth Stadtarchiv).

[70] Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 86.

[71] Gstrein 1987, 88.

[72] ‘sunst ist noch ein Klein peucklin, das haben die frantzosen und niderlender ser zu den Schwegeln gebraucht, und sunderlich zu dantz, oder zu den hochzyten.’ (there is also a small kettledrum, which the French and Netherlanders have often used, above all for dancing or for weddings). Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 91.

[73] Gstrein 1987, 89; Schwindt 2018, 81-2.

[74] Hoffmann-Axthelm 1983, 96. See also Green 2011, 17.

[75] Sumberg 1941, 88.

[76] Translation from Sutton 1967, 39, 47. See also Brunner 1983, 54-5.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Helen Coffey: “Civic and courtly dancing”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/en/node/19007> (2023).