Die weltlichen Lieder des Mönchs von Salzburg

Dieser Artikel wurde im Rahmen des ERC-Projekts „Music and Late Medieval European Court Cultures“ an der Universität Oxford verfasst. Dieses Projekt wurde vom Europäischen Forschungsrat im Rahmen des Forschungs- und Innovationsprogramms „Horizont 2020“ der Europäischen Union gefördert (Fördervereinbarung Nr. 669190).

Ein Panoptikum des mittelalterlichen Liedes

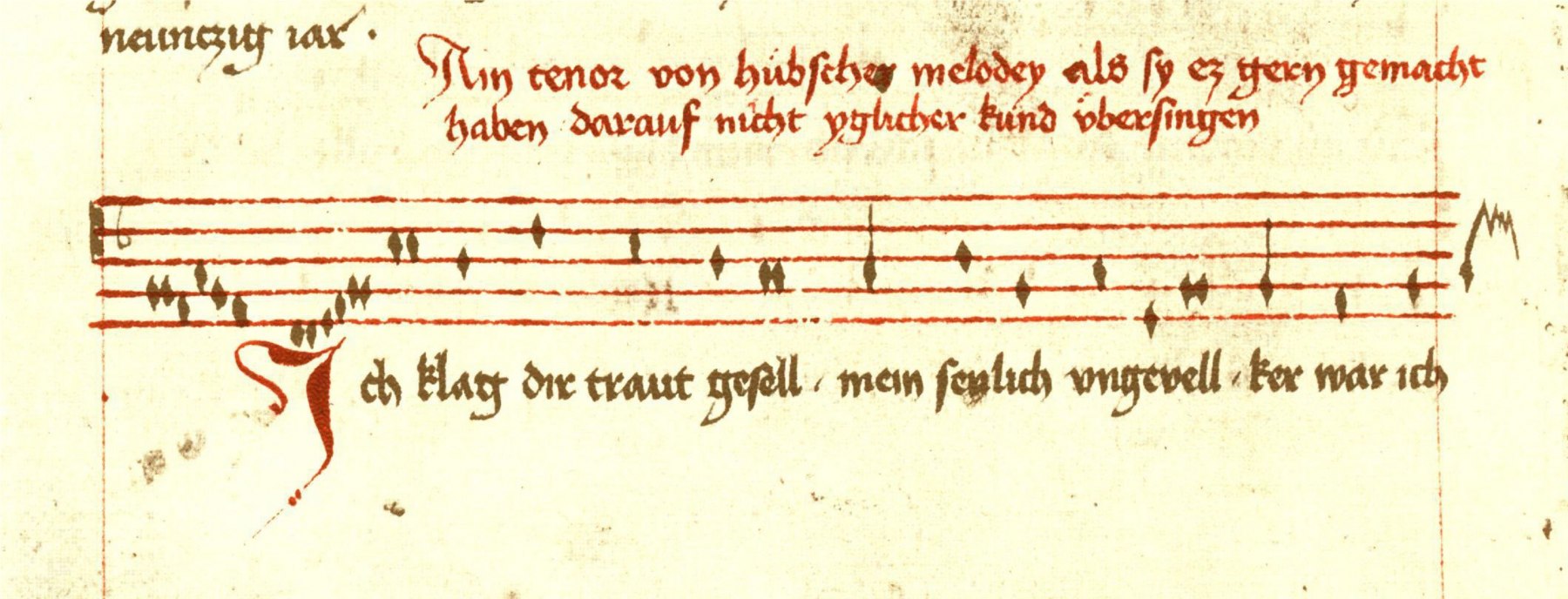

Die siebenundfünfzig weltlichen Lieder, die dem Mönch von Salzburg zugeschrieben werden, bilden eines der bedeutendsten Korpora des deutschen Volksliedes im Spätmittelalter. [1] Sie bilden die eine Hälfte eines umfangreichen Œuvres, dessen Rest aus neunundvierzig religiösen Liedern besteht, von denen viele Übersetzungen lateinischer Sequenzen und Hymnen sind (siehe » B. Geistliche Lieder des Mönchs von Salzburg).[2] Die weltlichen Lieder bestehen aus sieben mehrstimmigen Kompositionen - der frühesten notierten volkstümlichen weltlichen Mehrstimmigkeit im deutschen Sprachraum - und fünfzig einstimmigen Stücken. Sechzehn der einstimmigen Stücke haben eine sich wiederholende Form, die eine gewisse Ähnlichkeit mit der Ballade aufweist, die aber höchstwahrscheinlich nicht von den zeitgenössischen französischen Formes fixes abstammt.[3] (» Kap. The Monk’s Refrain Songs).Vierundzwanzig der einstimmigen Stücke haben eine strophische Form ohne Stollen, von denen drei in der Mondsee-Wiener Handschrift als „Tenor“ bezeichnet werden (» Abb. Ich klag dir, traut gesell).

Obwohl die Melodien dieser Stücke durchkomponiert sind, trifft dies nicht unbedingt auf die Texte zu, die eine Vorliebe für ausgefeilte Reimschemata zeigen und oft sogar so etwas wie eine Taktform verwenden. Diese Diskrepanz hat Reinhard Strohm zu der Vermutung veranlasst, dass „Tenor“ eigentlich eine Melodie impliziert, die ohne Worte übermittelt wurde und nach Belieben mit Worten unterlegt werden konnte. [4] Die übrigen weltlichen Lieder haben eigenwillige Formen, die sich einer Klassifizierung entziehen. Der Mönch nutzt diese Formen, um Lieder zu schaffen, die sich mit verschiedenen Themen befassen, darunter das Leben der Höflinge sowie die Probleme der Liebenden, vor allem die Trennung und die klaffer, die Leute, die am Hof Gerüchte verbreiten. Einige Lieder, wie die mehrstimmigen Martinslieder W54* Wolauf, lieben gesellen unverczait und W55* Martein, lieber herre und Neujahrslieder wie W29 Ain gelügkleich iar nach deiner gier, sind an bestimmte Jahreszeiten oder Feste gebunden, aber die meisten sind nicht anlassbezogen.

Die Überlieferung der weltlichen Lieder des Mönchs

Die Bezeichnung „Mönch von Salzburg“ ist wahrscheinlich eine Chiffre für mehr als ein Mitglied des erzbischöflichen Hofes von Salzburg. Obwohl unter der Schirmherrschaft des 1365-1396 regierenden Erzbischofs Pilgrim II. von Salzburg komponiert (zu Pilgrim siehe » Kap. Salzburg under Archbishop Pilgrim II), sind die weltlichen Lieder des Mönchs fast ausschließlich in Handschriften aus der ersten Hälfte und Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts überliefert.[5] Die bei weitem wichtigste Quelle für die weltlichen Lieder des Mönchs ist die Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift, A-Wn Cod. 2856 (vgl. » A. SL Die Notation der „Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift“).[6] Hier sind fast 90 Folios (drei Viertel der Liedersammlung, die zwischen Gesetzestexten und Konrad von Megenbergs Buch der Natur liegt) dreiundfünfzig Liedern des Mönchs gewidmet, und nur vier der weltlichen Lieder sind darin nicht verzeichnet. Im Gegensatz zur umfangreichen und verstreuten Überlieferung der geistlichen Lieder wurde dieses wichtigste Zeugnis der weltlichen Lieder höchstwahrscheinlich zusammen mit drei anderen wichtigen Zeugnissen in der Mitte des fünfzehnten Jahrhunderts im Salzburger Raum hergestellt:.[7] D, wie die Handschrift genannt wird, befand sich bekanntermaßen 1465, etwa ein Jahrzehnt nach dem wahrscheinlichen Herstellungsdatum, in der Sammlung des Salzburger Goldschmieds Peter Spörl. Die verstreute Überlieferung der Salzburger Mönchslieder ist beträchtlich, und es erscheinen immer wieder neue Konkordanzen, wie die in » A-Wn Cod. 5455 (besprochen von Marc Lewon: „A-Wn Cod 5455, fol. 180v – German “Tenors” from Vienna University“ in: Musikleben–Supplement).

Ich klag dir traut gesell

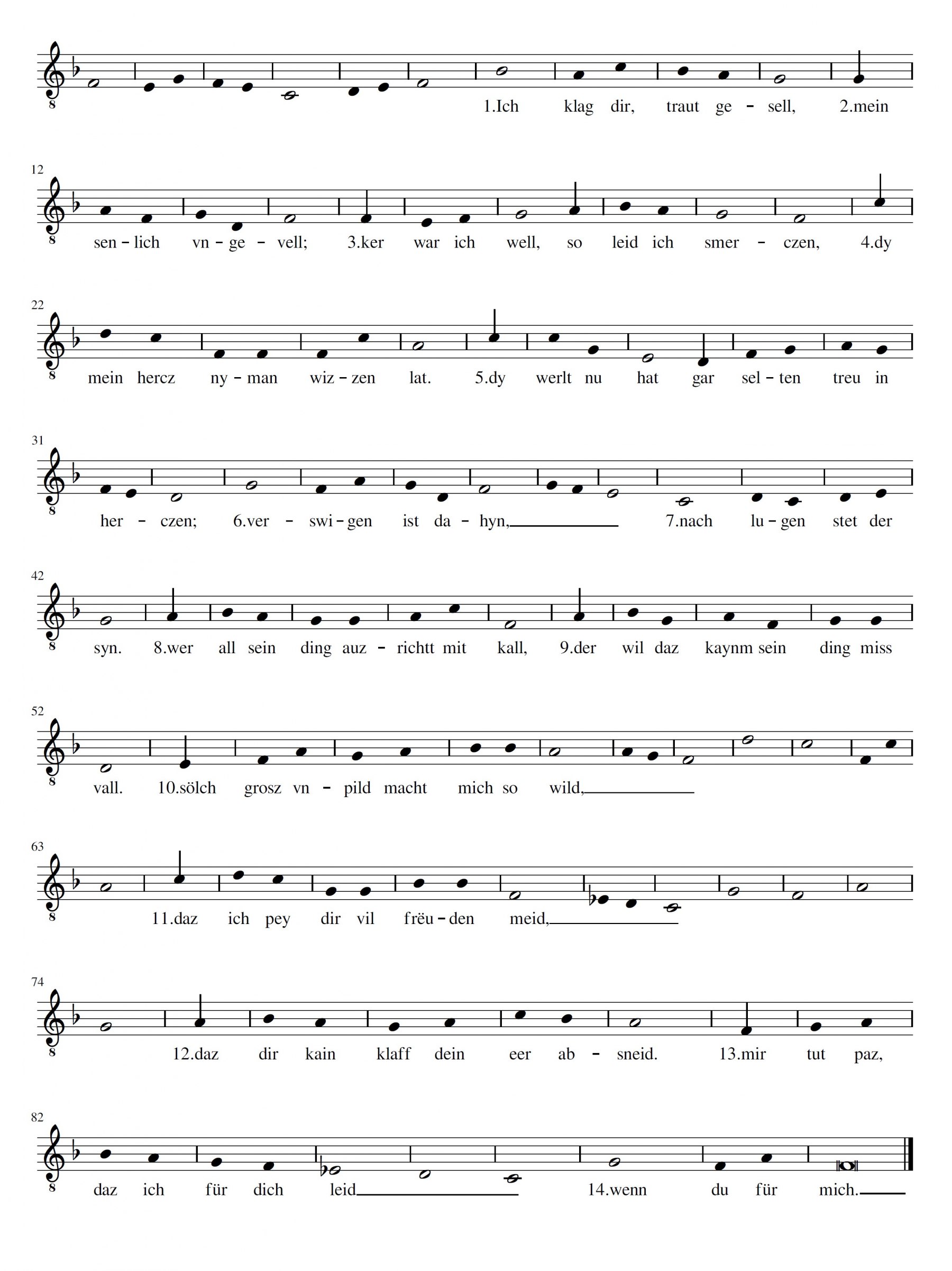

Einer der beiden Tenor-Stimmen, Ich klag dir, traut gesell (W8), bietet ein typisches Beispiel für die Anliegen, die in den Liedern des Mönchs angesprochen werden, und ist auch ein Beispiel für die meisterhafte Manipulation der Metrik, die den Korpus zu einem so wichtigen Werk macht. Der Tenor hat die strophische Form ●3a3a(3a)3’b 4c(2c)3’b 3d3d 4e4e(3f)3f ●4g ●4g4g3X. Hier steht das Symbol ● für ein Melisma, die eingeklammerten Reime sind zeilenintern, und X steht, der germanistischen Praxis folgend, für den Kornreim, bei dem in jeder Strophe ein einziger Reimlaut wiederkehrt, gebunden an dieselbe melodische Phrase. Zusammen mit der Komplexität ihrer Reimschemata sind das anfängliche Melisma und das Korn zwei der Hauptmerkmale der Tenorform, eines der charakteristischen Merkmale der Lieder des Mönchs (» Notenbsp. Ich klag, dir, traut gesell).

Notenbsp. Ich klag, dir, traut gesell

Ich klag dir, traut gesell: Lied des Mönchs von Salzburg, nach A-Wn Cod. 2856 („Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift“), fol. 190v.

Ich klag dir st auch eines der wenigen Lieder, für die das Manuskript D Hinweise auf eine mögliche Aufführungspraxis gibt.

Ain tenor von hübscher melody,

Als sy ez gern gemacht haben,

Darauf nicht yglicher kund übersingen.(Ein Tenor von hübscher Melodie, wie man sie früher gerne machte. Nicht jeder war in der Lage, dazu einen Diskant zu singen.)

Es scheint also, dass dieses Lied als Grundlage für den Discantus verwendet wurde.[8] Inhaltlich ist, Ich klag dir, traut gesell typisch für die Liebeslyrik, die einen großen Teil der in Salzburg entstandenen weltlichen Lieder ausmacht. Darin wendet sich der Sänger an seine Geliebte, spricht über seine Angst vor Gerüchten, die ihn daran hindern, mit ihr glücklich zu werden, und beklagt den Mangel an Ehre in der Welt.

Der Mönch von Salzburg ist damit typisch für den Liebeslied-Diskurs des späteren Mittelalters, in dem Liebesbeziehungen - im Gegensatz zu den verzweifelten Sehnsüchten des Minnesängers nach fernen höfischen Damen - stattdessen zu festeren Beziehungen geworden sind, in denen die Trennung der scheinbar einander zugeneigten Paare (und nicht die Weigerung der Dame, sich dem Sänger zu beugen) die größte Sorge bereitet.[9] In diesem Lied werden die Liebenden durch die Angst vor öffentlicher Entdeckung getrennt, und der männliche Sänger sehnt sich hier nach dem Tag ihres Wiedersehens (Str. 2, 13–14): “wy pald nymt end mein langez we,|wenn ich dich sich” (Wie schnell wird mein langes Leid enden, wenn ich dich sehe), bevor er die Bedenken des Höflings über die Verlässlichkeit seiner Mitmenschen bei Geheimnissen zum Ausdruck bringt:Bedenk, mein lobster hort,

Das pöse falsche wort

Groz lib zestort, und bis verswigen.

Dy lëut sint nu so wandelbër,

Sy sagent mër vnd lazzent nicht geligen (Str. 3, 1–5)(Bedenke, mein lieber Schatz, dass böse, falsche Worte den größten Mann vernichten können, und schweige. Die Menschen sind jetzt so wandelbar, sie erzählen solche Geschichten und hören nicht auf)

Das Lied verbindet also eine Darstellung der Gefahren des Lebens am Hof im Allgemeinen, vor allem der Möglichkeit, dass Gerüchte kursieren, selbst wenn - und vielleicht gerade weil - sie unbegründet sind, mit einem gewissen Maß an laudatio temporis acti, dem Lob der vergangenen Zeiten. Auf diese Weise werden die Verästelungen der kleinlichen Persönlichkeitspolitik und der Streitereien des höfischen Milieus wirkungsvoll untersucht, wobei die Möglichkeiten komplizierter und erfindungsreicher Reimschemata genutzt werden, um die Echokammer des Hofes zu imitieren.

Salzburg unter Erzbischof Pilgrim II.

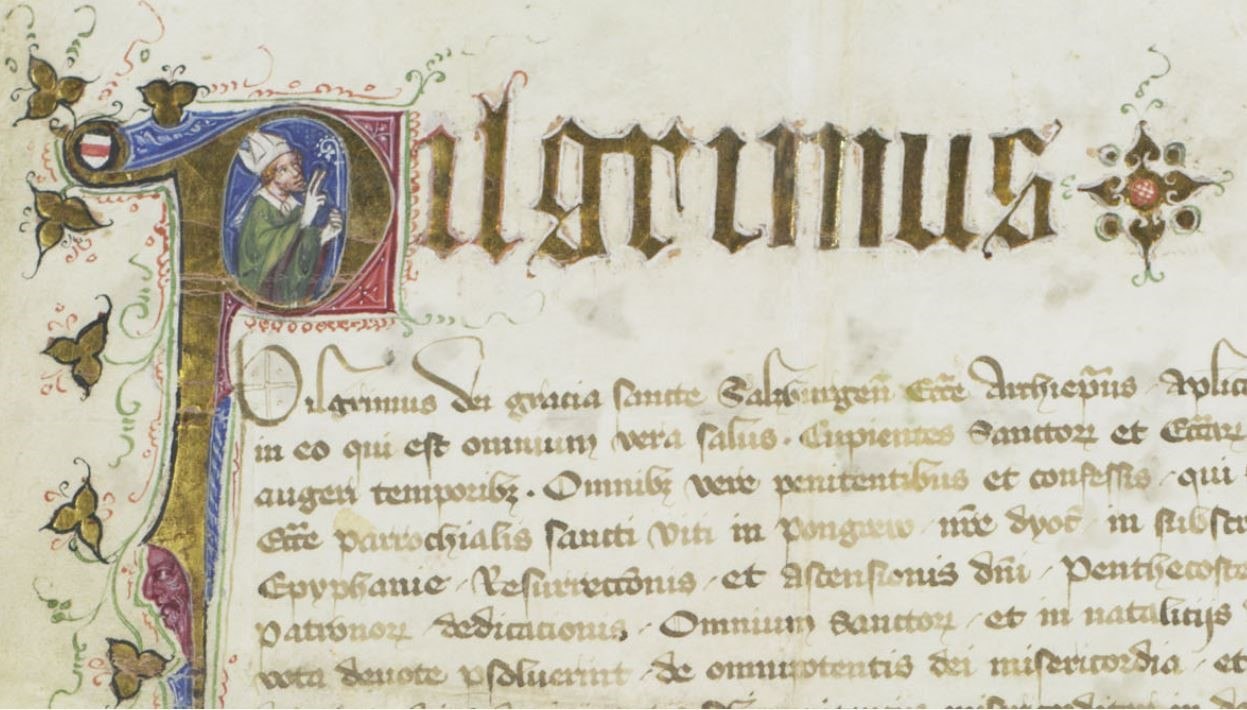

The specific historical court that is the implicit background to the Monk’s songs is that of Archbishop Pilgrim II von Puchheim, who ruled Salzburg as an independent ecclesiastical principality between 1365 and 1396. (See » Fig. Throne Seal Pilgrim’s II. of Puchheim)

The archbishop’s worldly authority extended over most of the current Bundesland Salzburg and included possessions in Styria and Carinthia, and in Carniola in modern Slovenia. Simultaneously, Salzburg’s ecclesiastical ambit (the two did not always overlap) extended over suffragans in modern Bavaria (Freising, Regensburg, Passau and Chiemsee), in Carinthia (Lavant, Gurk) and Styria (Seckau), as well as Brixen/Bressanone in modern Italy. Enjoying close connections with the King of the Romans Wenceslas in Prague, as well as long-standing familial ties to the Habsburg dukes of Austria, Archbishop Pilgrim and his court were well-placed to benefit from the cultural capital of the time.[10]

Pilgrim’s reign was a combination of great political exploits on a regional, indeed continental, scale, improved fiscal security and management of the Hochstift’s resources (notably the essentially important salt-works, but also shipping along the Salzach). It is no surprise that his portrait was painted even in charters concerning his ordinary ecclesiastical administration: see » Fig. Throne Seal Pilgrim’s II. of Puchheim.

Thus when Pilgrim’s tombstone described him as being ‘potens in opere et sermone’ [‘powerful in deed and word’], this is not merely empty rhetoric.[11] The thirty years of his reign were a period of great expansion of the Hochstift Salzburg, and saw it reach its greatest territorial extent with the acquisition of the provostship of Berchtesgaden in 1393.[12]

While the horizons of the Hochstift at large expanded, the court itself became more introverted, as more positions of authority in Salzburg were handed off to Pilgrim’s close relatives. Multiple brothers and brothers-in-law became Hauptmann of Salzburg (the master of the Hohensalzburg fortress high above the city and officer responsible for law and order).[13] Similarly, the suffragan bishoprics of Chiemsee and Seckau went to Pilgrim’s nephews, Georg and Johann von Neidperg respectively.[14] This flourishing nepotism was accompanied by an apparent reduction in the size of the archbishop’s privy council (although it has been suggested that this is the contrast between a larger ‘plenary’ council and a smaller daily circle[15]). Pilgrim’s reign also sees the appearance of new office-holders in the council, which until the beginning of the fourteenth century had been largely clerical: now these were mainly laymen, Vizedom (1360), Oberster Schreiber and Hauptmann (1370), Domdechant as official and the chancellor (1377), and Hofmarschall (1382).[16] This change in the composition of the court no doubt had its effect on the artistic production in Salzburg.

Der Hof in den Liedern des Mönchs

The historical court of the Archbishop of Salzburg has its literary-musical echo in a number of the Monk’s songs. One of the most interesting of these is W19, Wier, wier der fünfzehent an der schar, which, on behalf of all the members of the court, addresses all the women who have injured them. Imitating exactly the form of a charter, from the introductory formula to the place and date at its end, Wier, wier is typical of the ingenious and playful approach to song-writing in Salzburg. Proposed by Franz Viktor Spechtler to have been composed at the Reichstag in Nuremberg in 1387, it is above all interested in the responsibilities of the good member of the courtly society,

Gesellschaft ist also gericht,

Das kain artikel sey nicht pricht.

Ein schalkch verirret gar die slicht;

Wie wol sölich dingk durch guet geschicht,

der volg yem unnser keiner gicht;

Den süll wir hassen vestiklich,

Wenen wir sein purgersinn unstët (Str. 2, 5–11)(Courtly society is so inclined that it breaks no article of faith. A trouble-maker confuses the flow of things. However easily such a thing could happen for the best of reasons, no one among us will follow such a canker. We should instead hate him with passion, if we think his civic sense is insecure.)

Those, the song goes on, who are inconstant will not be allowed into the council. The courtly society is one that depends on trust. Where elsewhere (as in Ich klag dir, traut gesell) the songs play through notions of loyalty under the guise of the amatory relationship, in Wier, wier, the importance of trust to one’s social standing is discussed more or less openly here. While the amatory metaphor (one that reaches back to the earliest days of Minnesang in the twelfth century; see » B. Minnesang und alte Meister) is evoked at the beginning of W19, this song is all about standards in public life and conformity to conventions, something underscored in playful fashion by its already mentioned imitation of a charter.

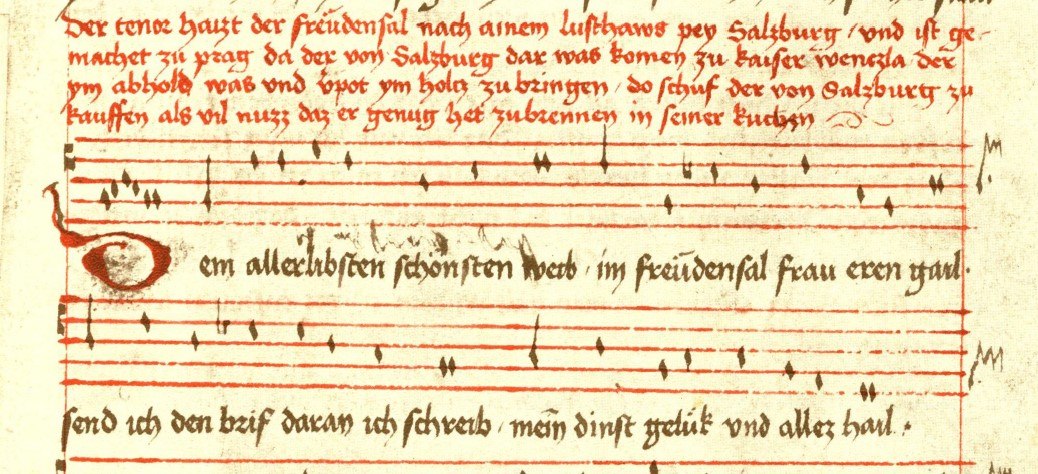

One of the most commented pieces in the Monk’s secular corpus, Der frëudensal: Dem allerlibsten schönsten weib (W7), which takes the form of a letter to “frau Erengail” (Lady Greedy-for-Honour) is dated to carnival (Fastnacht) 1392. The supposed writer describes himself in the piece as “pilgreim”, a play on the name of the Archbishop that fed the idea, now generally abandoned, that Pilgrim von Puchheim was himself the Monk.[17] This connection to the prelate is made all the more concrete by the rubric appended to the poem in MS D (A-Wn Cod. 2856), f.190r. It describes the occasion for the apparent composition of the song Dem allerlibsten schönsten weib, the tenor of which it calls “Der Freudensaal”, during a visit by Pilgrim von Puchheim to the King of the Romans Wenceslaus IV in Prague. (See » Fig. Der tenor haizt der freudensaal: Monk of Salzburg)

Der tenor haizt der Frëudensal nach ainem lusthaws pey Salzburg, und ist gemacht zu Prag, da der von Salzburg da was komen zu kaiser Wenczla, der ym abhold was und verpot ym holz zu bringen. do schuf der von Salzburg zu kauffen als vil nuzz, daz er genug het zu brennen in seiner kuchen. (D, f. 190r)

(This tenor is called ‘The House of Joy’, after a pleasure house near Salzburg, and was made in Prague, when the Salzburger (sc. Archbishop Pilgrim) had gone there to see Emperor Wenceslas, who was unkind to him and forbade anyone to bring him wood. So the Salzburger required so many nuts to be bought that he would have enough to burn in his kitchen.)

The most extensive of any of the rubrics in the manuscript, it alleges that the song was composed in Prague, although Pilgrim is not recorded as having visited the city that year. Whether accurate or not, the rubric responds to the reality effects written into the song text and offers the fifteenth-century user a substitute connection with the fourteenth-century events described.

Die Refrain-Lieder des Mönches

One of the peculiarities of the Salzburg corpus is the group of sixteen songs using a form that combines elements of the virelai and ballade. These were a mainstay of French vernacular song culture from the mid-thirteenth century and found their classical expression in the work of Guillaume de Machaut.[18] The cluster of songs in Salzburg exhibiting this form type has normally been interpreted as evidence of the closeness of cultural as well as diplomatic ties between the Hochstift and the French-speaking world (for another instance of these connections, see » Ch. Networking the Monk of Salzburg: Ju, ich jag). It has also been suggested, though this seems highly unlikely, that inspiration came more or less directly from Machaut himself by way of Prague, where he was secretary to King John of Luxemburg for more than a decade, and where Archbishop Pilgrim visited John’s grandson Wenceslas IV, King of the Romans, on a number of occasions (» Ch. The Court in the Songs of the Monk).[19] The refrain songs produced in Salzburg share with the French type, exemplified by Machaut, the general AABB form, but depart in the greater length of their refrain, which always follows the strophe (whereas Machaut’s sometimes precede it), and the prevalence of a brief initial melisma to both A sections. As such it is most probable that the Salzburg refrain songs drew their inspiration from earlier German traditions or perhaps from Romance trends from before the crystallization of the classical formes fixes.

For example, the May song W50, Seint röslein, plüemlein maniger lay has the form:

A

A

B

B (Refrain)

●4aaa6b

●4ccc6b

4dedd(d)ffe

4ghgg(g)iih

The singer focusses on how he can win “von prawnen wolgemuet|ain krënzlein […] von meiner liebsten frawen” and dance with her in the circle. The association of the chaplet with female virginity, a standard topos since the earliest courtly love-lyric, is heightened by the fact that this one is made of marjoram, which flowers in the autumn and was valued as an aphrodisiac.[20] Beyond this, the colour brown was traditionally associated with the female genitalia. The second strophe leaves the allusive in favour of the obscene, talking about flowers that lie above the “Happy Valley” (“frëwdental”, Str. 2, 1). Evidently, the fact that these songs were produced in the shadows of a Prince of the Church had little impact on their contents. It is perhaps a little more surprising that the same material could be found in a monastic context: the first strophe of this song was copied into » D-Mbs Clm 14256 (f.105r) at the Abbey of St Emmeram in Regensburg alongside the Monk’s translation of the Easter sequence Mundi renovatio.[21]

Wer sang für wen in Salzburg?

The question of exactly who composed the songs often only labelled as münchs in many of the manuscript sources has elicited many different answers (on this question see further Stefan Engels » Kap. Widersprüchliche Forschungsmeinungen zum Mönch and » Kap. Schriftliche Zeugnisse über den Mönch). As noted (» Kap. A Panopticum of Song) it is highly unlikely that all 106 songs attributed to the Monk were indeed composed by a single individual. Christoph März, in his edition of the secular songs, attempted to attribute each of the secular songs to one of three ‘layers’(Schichten). Layer II, that furthest from the core—and thus furthest from the individual “Monk”—is particularly rich in refrain forms. This invites the suggestion that the refrain songs offered a flexible basis for less gifted poets among the courtiers at Salzburg to join in the common interest in vernacular song. For example, the songs W48, W49 and W53 (all in März’s Layer II, and all unique to the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift, A-Wn Cod. 2856) are marked by a certain derivative quality. W48, ‘Ich het czu hannt gelocket mir’, as Ingrid Bennewitz-Behr proposed, imitates a song by Heinrich von Mügeln.[22] The fact that it might be doing this in the female voice makes it unique in the Monk corpus, where female voices only appear in the context of dialogue songs such as the polyphonic pieces W3, 4 and 5, and the tenor-type song W57* (W4: » Hörbsp. ♫ Untarnslaf – Das kchúhorn).

The presence of female voices supports the idea that the Monk songs were responding to a highly varied audience.[23] Salzburg was thus, it seems, a court where participation in the making and appreciation of song was constitutive to the establishment and delineation of a courtly community. We can perhaps also draw comparisons with narrative sources from the time.[24]

Die Vernetzung des Salzburger Mönchs: Ju, ich jag

As has already been noted, the Monk’s secular songs record the extensive cultural networks that fed Salzburg in the fourteenth century. Most prominent among these is the Monk’s three-part canon Ju, ich jag, which is a contrafactum of the Old French chace Umblemens vos pri merchi.[25]

By and large, the Monk does not seem to engage with the French text. The label “chace” implies a hunting scene, but beyond the nod in the Monk’s incipit (“I hunt with my heart by day and night”), Ju, ich jag is not about hunting nor even, really, a chase of any kind.[26] Rather it is for the most part a highly detailed description of the perfect courtly lady, as a kind of projection screen for male desire and medieval discourses on beauty. Following the ancient topos whereby external beauty reflected inner virtue, the singer declares that his lady is perfect in every respect:

Sust all tail hant gelück und hail,

Ynnikleichen, mynniklichen,

Schön polieret, durch visieret.

Des mues ymmer haben dangk

Die lieb natur,

Dy pildet sülch figure. (E2, 41–46)(And so all parts have joy and salvation,

Inwardly, lovingly,

Finely polished, thoroughly sculpted

For that we must forever thank lovely Nature,

Who shapes such figures.)“Polieret” and “durch visieret”, seem to indicate that the Monk was indeed, in some measure, acquainted with French, and that therefore—presuming that he was in possession of both text and melody of Umblemens—it was indeed a choice available to him to engage with the French song or not. It is witnessed only once in its entirety and with music in the Ivrea manuscript (I-IV 115), but is also mentioned in the Trémoïlle manuscript (» F-Pn nouv. acq. fr. 23190).[27] The first of these witnesses was probably compiled around 1385 by Savoyard clerics at Ivrea in northern Italy; the manuscript testifies to strong ties to the Valois court in Paris, and by extension to the Papal court at Avignon.[28] The second witness is in the index to the now lost Trémoïlle manuscript, which seems to have been copied by one of Charles V’s chaplains, Michel de Fontaine, most likely for Jean II or the duke of Burgundy.[29] Ju, ich jag in this way bears witness to the adoption in Salzburg of musical art produced for the very highest ranks of fourteenth-century French society.

Die Rezeption der weltlichen Lieder des Mönchs

The earliest traces of the Monk’s songs point to a perhaps unsurprising popularity among monastic and clerical milieux, for example at St Emmeram’s abbey in Regensburg[30] (see » Ch. The Monk’s Refrain Songs), and at Göttweig, where a Latin version of the Martinmas canon W55*, Ain radel: Martein, lieber herre, was composed.[31] (This last can be heard here: » Audio ♫ Martein, lieber herre.) This parallels the early appearance of religious songs by the Monk in the Engelberg manuscript (» CH-EN, Cod. 314), where the future abbot Walther Mirer appears to have copied three of the Monk’s translations, G6, G40, and G47 before 1380, most probably not long after their composition.[32] Further important evidence of the circles in which the Monk’s music first achieved popularity is the witness to the Monk’s ‘Taghorn’ and a number of refrain songs among similar compositions by other poets in the Sterzing miscellany (» I-VIP o. Sign.). This manuscript from the first decade of the fifteenth century, perhaps compiled among the cathedral canons of Brixen or at the Augustinian house at Neustift/Novacella,[33] bears witness to the tastes of a noble, secular-clerical milieu, similar to that which had originally given rise to the songs in Salzburg.[34]

Later in the fifteenth century, a number of cases bring the Monk into contact with Oswald von Wolkenstein, active around half a century after the Monk (see » B. Oswalds Lieder). While these are above all cases of the Monk and Oswald being transmitted together (for instance Oswald’s Mittit ad virginem alongside the Monk’s translation in MS A, » D-Mbs Cgm 715), there are two instances in which it seems that Oswald did indeed know songs by the Monk. First, the Monk’s W15, Ain liblich weib, der zarter leib, a song with a curious form that combines elements of the tenores and the refrain songs, is imitated by Oswald in his Kl 78, Mich tröst ein adeliche mait (März 1999, 404–406), which systematically re-uses the same rhyme sounds. It has also been suggested, although it is hard to prove conclusively, that Oswald knew Iu ich jag (W31, » Ch. Networking the Monk of Salzburg: Ju ich jag), and quoted in his song Kain ellend tet mir nie so and (Kl. 30).[35]

Any direct knowledge may have come via the Augustinian foundation at Neustift or the cathedral convent at Brixen (a suffragan see of Salzburg), with which Oswald had long-standing connections, not least that his son Michael became a cathedral canon in Brixen in 1440.[36]