Non-mensural polyphony in secular repertories: Oswald von Wolkenstein and the Monk of Salzburg

Oswald and the tradition of non-mensural polyphony

Oswald von Wolkenstein’s polyphonic output can roughly be categorised in two groups; one of them consists of contrafacta. The other has proved difficult to place and in past scholarship has been referred to by a diversified terminology applicable to sacred repertories, which includes the expressions ‘archaic’, ‘monastic’ (‘klösterlich’) and ‘organum-like’ (‘organal’).[1] One additional term, coined specifically for this group of Oswald’s secular polyphonic songs, was introduced in 1977 by Ivana Pelnar[2] and was designed to suggest an origin from local, possibly ‘oral’ practices: ‘bodenständig’. This term translates as ‘native’, ‘local’, or ‘down-to-earth’, and besides referring to an autochthonic repertory has implications of the ‘simple’, the ‘rural’ and the ‘rustic’. This term also hints at a ‘peripheral’ repertory, but at the same time dodges the question of provenance to some extent, since the assumed models would presumably have been unwritten and thus untraceable in manuscripts other than Oswald’s own codices. Within his codices the specimens would thus count as a ‘freak occurrence’ – a reasoning that carries the seeds of a circular argument. Furthermore, unlike the first group of polyphonic songs, the contrafacta, these songs were assumed to be Oswald’s own attempts at polyphonic composition, partly because their notation and counterpoint appear to be by a non-expert and partly because none of them (with one exception) have concordances outside his manuscripts. The question of Oswald’s musical training had been the subject of previous scholarship but could not ultimately be solved.[3] However, the fact that a substantial part of his polyphonic output consists of contrafacta while this remaining part appears to be of a humbler stylistic level paired with a lack of concordances, could point to Oswald’s authorship and level of musical training. This assumption is supported by the observation that the bulk of this particular repertory was added to Oswald’s first song collection (WolkA)[4] as a secondary layer only after a substantial repertory of contrafacta had been entered, probably in the wake of the Council of Constance.[5] Therefore, Oswald’s experiences at the Council appear to have triggered a boost of poetic and musical activity, resulting in new monophonic songs and contrafacta followed by a surge of own polyphonic works.[6]

In my previous work on Oswald’s polyphonic songs I have encountered the same difficulties as previous scholars in defining this special group of songs, and – at least regarding the terminology – have fallen in some of the same traps: while rejecting the term ‘bodenständig’ (‘native’) to describe it, I did use ‘archaic’ and embraced ‘organum-like’ (‘organal’). Yet, this group is essentially of the same category as the sacred repertories that have been characterised as ‘non-mensural polyphony’ (» A. Kap. Zum Begriff der nichtmensuralen Mehrstimmigkeit). It would, therefore, not represent an isolated repertory but could be seen as embedded in a common practice. The historical and theoretical background of this practice has first been discussed in English in Fuller 1978.

Notations for polyphony in the Wolkenstein codices

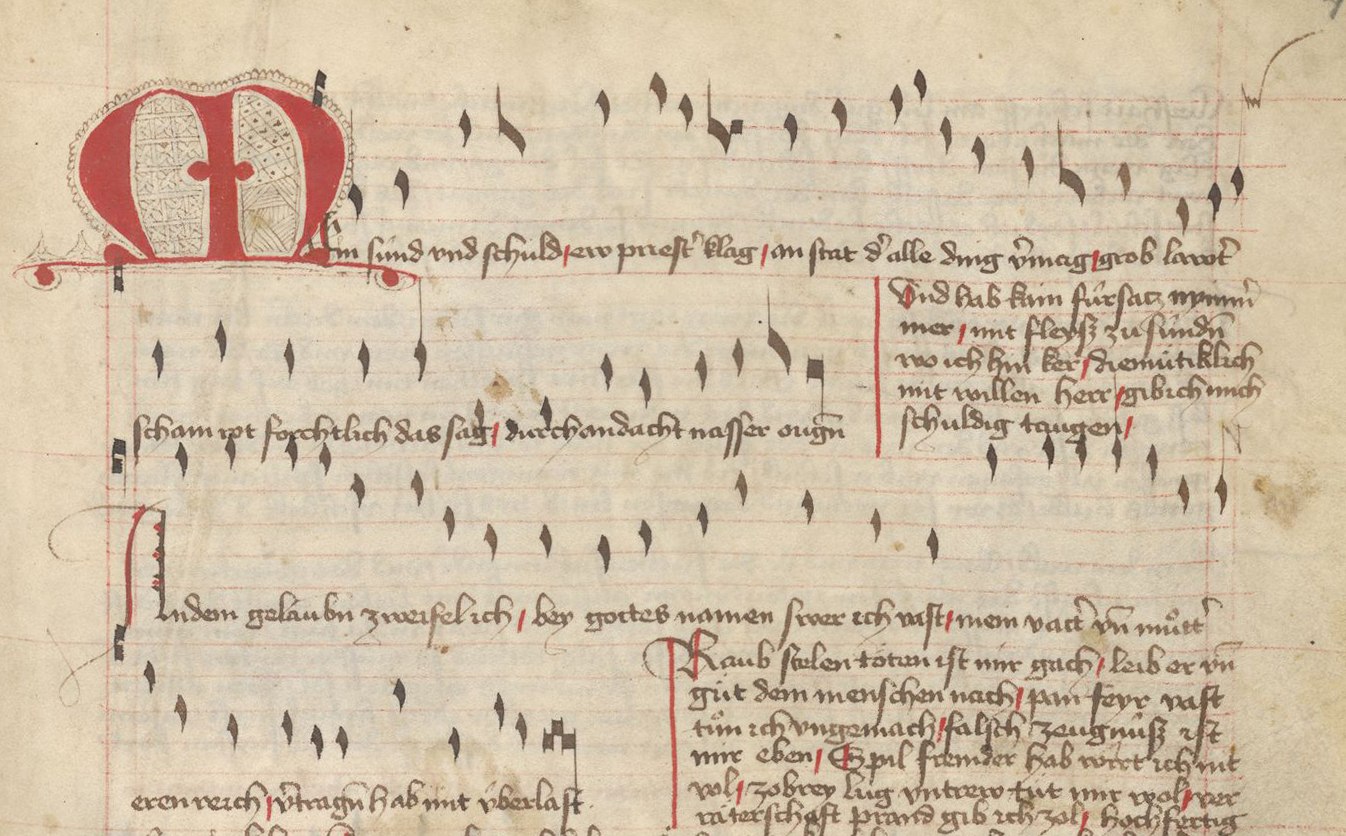

The defining aspect of these repertories is that they are unmeasured, which, when applied to Oswald, appears to be a contradiction in terms since all his surviving music is notated mensurally. The use and meaning of mensural notes in the Wolkenstein codices, however, appear to differ according to context: while the scribes made standard use of the notational signs for the contrafacta to precisely regulate the interaction of the voices, they applied the mensural note shapes more creatively for the other group of songs, describing rather than prescribing a practice for which notation—in principle—was not required.[7]

This latter use of mensural note signs can be further differentiated, and – in its different forms – abundantly occurs also outside Oswald’s song manuscripts. It can, for instance, be found in the Neidhart œuvre of the Eghenvelder Liedersammlung (» B. Kap. Eine studentische Neidhartsammlung aus Wien), in the Lochamer-Liederbuch (D-B Mus. ms. 40613), or in the manuscripts containing the songs of the Monk of Salzburg (» B. Geistliche Lieder des Mönchs von Salzburg; » B. Secular Songs of the Monk of Salzburg). It manifests itself primarily in two forms: a semi-mensural and a structural use. The semi-mensural use can consist of mensural note signs in an otherwise non-mensural environment (for instance, chant notation) to clarify small-scale rhythmic relationships, such as upbeats, the placement of surplus syllables, and so on, or to provide a suggestion for a general performance rhythm. It can, however, also appear in the form of a seemingly precisely rhythmised melody. This special case of semi-mensural usage comes with a syllabic underlay of a German verse text with alternating stresses and usually consists of a regular alternation between a longer and a shorter note value in triple metre, usually semibrevis and minima, representing accented and unaccented syllables, respectively. Occasionally it also appears in duple metre. The resulting musical rhythm is a depiction of the verse metre of the underlying text and serves as a point of reference rather than a prescription for the performer, which is why I named it ‘reference rhythm’.[8] Since the reference rhythm is generated from the text (unlike the first and second rhythmic modes of the >Ars antiqua<) it is descriptive and implies performative flexibility. This, in turn, means that the essence of the melodic structure is not affected by a performative deviation from the rhythmic profile. Besides, what at first glance may look like a coherent use of mensural notation reveals numerous inaccuracies when looked at more closely. This semi-mensural use of mensural notation functions under the assumption that its meaning is clear from the context.

The other irregular use of mensural notation, the structural use, is non-mensural in essence. Mensural note shapes are employed here to visualise the structure of a melody with no hint at a performance rhythm: minimas represent upbeats, semibreves are equivalent to the puncta of chant notation and serve to notate the pitches of a melodic line, breves and longas indicate cadence notes, and the semiminima is occasionally used as custos (» Abb. Structural use of mensural note shapes, Oswald von Wolkenstein).

Although notations in pure reference rhythm as well as pure structural use can be found in all the above sources, both forms can also flow into each other and interact freely with other forms of semi-mensural notation, such as >stroke notation<.[9] All of them, however, are mainly reserved to record monophonic songs. Their use for some of the polyphonic pieces in the œuvre of Oswald von Wolkenstein clearly links this repertory to the world of monophony. In fact, the majority of this repertory appears to be equivalent to the concept of ‘cantus planus binatim’ (» Kap. Zum Begriff der nichtmensuralen Mehrstimmigkeit) a sort of ‘embellished’ or ‘enhanced monophony’ that employs a wide range of practices including fifthing (‘quintieren’) and extemporising upper voices (‘übersingen’): two techniques that are actually mentioned in Oswald’s song texts. And, as regards the term ‘binatim’ (‘in pairs’), all of the Oswald songs in question are for two voices.

Another comparable German repertory at the cross-roads between monophony and polyphony is the ‘polyphonic’ output of the Monk of Salzburg. Of his eight surviving polyphonic songs (all of them secular)[10] at least six contain aspects of non-mensural polyphony. Even though his compositions predate Oswald’s by at least one generation, the earliest transmitting sources appear only after the mid-fifteenth century, well after the Wolkenstein codices were written (WolkA, c. 1425; WolkB, c. 1432). The manuscripts with the Monk’s polyphonic songs present concordances in a wider range of sources and with a wider range of notations, including chant notation, which confirms this repertory’s affiliation to non-mensural polyphony as well as monophonic music. All voices in both repertories (Oswald’s and the Monk’s) are notated separately, according to contemporary custom – even though a notation in score format, which is usually found in the sources of sacred non-mensural polyphony (as for example » Abb. Viderunt omnes/Vidit rex, » Abb. Jube Domne – Consolamini), would have been more appropriate for a repertory that does not rely on exact rhythmic notation.

Open borders between monophony and polyphony

Both the Monk’s and Oswald’s surviving songs were in modern scholarship traditionally sorted into a monophonic and a polyphonic repertory. This division finds some historical justification in that Oswald’s polyphonic songs tend to stand in blocks in his codices and the Monk’s are also usually sorted together in the transmitting sources, even opening the first section of secular songs in the main manuscript dedicated to his output, the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift (» B. SL Die Notation der ‘Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift’). Both authors, however, seem to have considered polyphony mainly as a performance option, not as a compositional concept, particularly when it was non-mensural. When setting aside those songs which appear to require polyphony in order to function, such as the double-texted, motet-like compositions and those that employ hoquetus-like interjections of the upper voice to complement the text, the remaining repertory could work just as well in monophonic versions. In fact, the sources for both authors attest to such a practice.

A number of polyphonic songs by Oswald in both the contrafacta and the non-mensural repertories appear polyphonic in only one of the two manuscripts, while the other provides a monophonic version. The non-mensural repertory alone has four such cases out of twelve, though two of them (Kl 77 and Kl 94)[11] are monophonic in one of the manuscripts for other reasons. The monophonic versions of the remaining two (Kl 37/38 and Kl 68), however, represent conscious editorial choices. Of the six pieces by the Monk of Salzburg featuring non-mensural polyphony all but one also survive in monophonic versions in the transmitting sources. This even includes two double-texted, motet-like songs: W 3,[12] the ‘tenor’ of which (if the term applies here) apparently received an interlinear adaptation for the monophonic version: its words and the melody have been added to the beginning of each strophe; and W 5, an aubade (alba, ‘Tagelied’) with a three-way dialogue between two lovers (discantus) and a watchman (tenor), from which one of the sources simply omitted the voice of the watchman to render it monophonic. This means that even those songs which appear to require a second voice for textual reasons, were not necessarily immune to monophonic treatment – though it seems that in these cases the polyphonic version preceded their monophonic redaction.

While the double-texted songs in the sources of Oswald and the Monk naturally have text underlay in both voices, some of the notations of single-texted songs have only one texted voice. For Oswald this occurs mainly in the WolkB manuscript, where texting only the tenor was first and foremost a layout choice. In some of these cases WolkA presents a version with a fully texted discantus or with line incipits that imply texting. For the Monk this occurs only for W 1 and W 2 in the main manuscript, both with untexted drone-like voices that do not require a full underlay to clarify their operating principle. It is, therefore, clear from context that partial texting in these repertories does not translate into an intended instrumentation, where, for instance, only the texted voice is sung while the other may have been played on an instrument. This is a vocal repertory.

These observations confirm, first, that the modern distinction between monophony and polyphony for these repertories is clearly outdated. Second, they suggest that non-mensural polyphony was a performance option for the entire monophonic repertory of both authors. The associated practices could easily be applied to any monophonic song in either of the two œuvres.[13]

Oswald’s repertory of non-mensural polyphony

The following table contains the corpus of two-voice non-mensural polyphony in the œuvre of Oswald von Wolkenstein. It is an excerpt of the list of polyphonic pieces from my article on Oswald’s polyphonic music.[14] It contains twelve songs—one of them with two alternative texts (Kl 37/38) (see Table I.)

- * Kl 37 Des himels trone & Kl 38, Keuschlich geboren: WolkA, fols 34v–35r & 46r, 2vv; WolkB, fols 15v–16r), 1v

- + Kl 51 Ach senliches leiden: WolkA, fols 20v–21r, 2vv; WolkB, fol. 22r–v, 2vv

- Kl 68 Mein herz júngt sich: WolkA, fol. 30v, 2vv; WolkB, fol. 29r, 1v

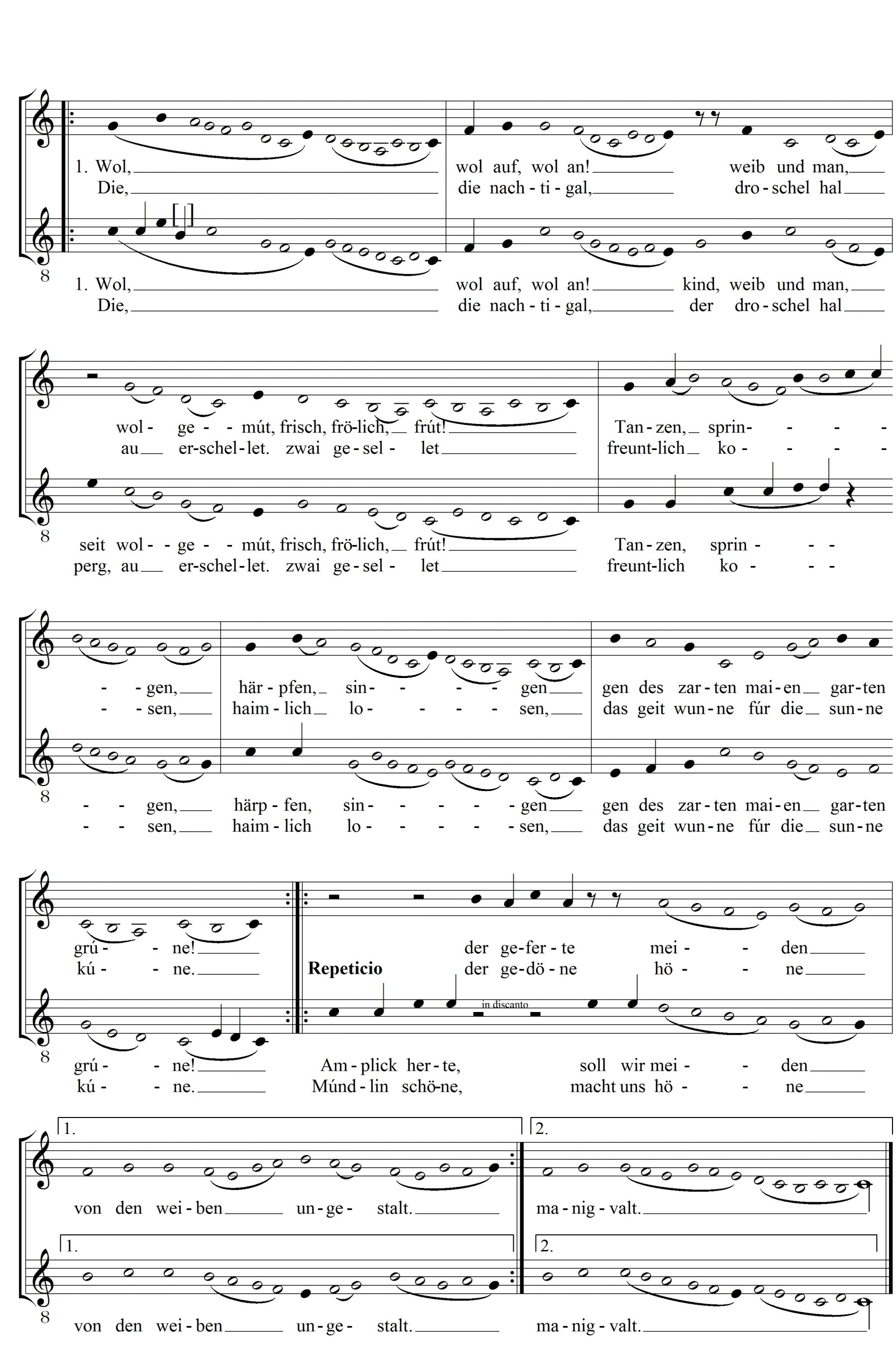

- * Kl 75 Wol auff, wol an: WolkA, fol. 35r, 2vv; WolkB,fol. 31r, 2vv

- * Kl 76 Ain graserin:WolkA, fol. 35v, 2vv (discantus blackened); WolkB, fol. 31v, 2vv

- * Kl 77 Simm Gredlin, Gret:WolkA, fol. 36r, 2vv; WolkB, fols 31v–32r, 1v (discantus intended but not filled in)

- * Kl 79 Frölich so wil ich aber singen: WolkA, fol. 39r, 2vv; WolkB, fols 32v–33r, 2vv

- + Kl 84 Wol auff, wir wellen slauffen: WolkA, fol. 45r, 2vv; WolkB, fols.34v–35r, 2vv

- + Kl 91 Freuntlicher blick: WolkA, fols 53v–54r), 2vv; WolkB, fols 37v–38r, 2vv

- - Kl 93 Herz, prich: WolkA, fol. 21r, 2vv; WolkB, fol. 38v, 2vv

- - Kl 94 Lieb, dein verlangen: WolkA, fol. 18r, 2vv; WolkB, fol. 38v, 1v (discantus intended but not filled in)

- Kl 101 Wach auff, mein hort: WolkA, fol. 56r–v, 2vv; WolkB, fol. 40v, 2vv

Table I: Two-voice non-mensural polyphony in the œuvre of Oswald von Wolkenstein.

All of these songs have in common that their two voices are largely homophonic, which means that even if the notation is not entirely clear, the coordination of the two independently notated voices (with some exceptions) does not pose particular problems. Also, the notation of these songs, in contrast to that of the contrafacta, does not feature a great variety of rhythmical values and mostly employs semibreves and minims. Certain techniques of non-mensural polyphony, such as fifthing and contrary motion, as well as the semi-mensural concept of the reference rhythm occur in almost all of them. Elements of all these can be seen below in » Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an (Kl 75).

While fifthing is omnipresent throughout this song piece, contrary motion occurs over the words ‘gen des zarten maien garten’ towards the end of the A-section, and in its first ending (ouvert). The minim upbeat after the initial melisma over the first word ‘wol’ as well as the use of the semiminima as a custos (visible in the original manuscript) both hint at a structural use of mensural notation. Reference rhythm is quoted a few times, most noticeably to the words ‘Tanzen, springen’ – probably also referencing dance – and at the beginning of the refrain ‘Amplick herte, der geferte soll wir’.

Yet, the corpus can be further divided into groups of similar construction. The five songs marked with an asterisk (*) share noteworthy notational traits, particularly an abundant use of red notation, as well as other striking features, such as occasional breaks of the homophonic setting, the inclusion of hoquetus passages, and an extravagant melodic construction that at times can seem almost erratic. Four of these five stand together as a group in both manuscripts.[15] The three songs marked with a plus sign (+) are strictly homophonic, melodically fluent while featuring drone-like passages, they present a reference rhythm in duple metre, and do not employ red notation. Even though their notation seems to add up rhythmically, the fact that they use reference rhythm indicates their semi-mensural structure, hinting at a certain degree of rhythmical freedom in performance. They also represent a group of pieces where the tenor rather than the discantus might be the added voice, similar to the ‘pumhart’ songs by the Monk of Salzburg (see below). Two of the remaining four songs, Kl 93 and Kl 94, are marked with a minus sign (-): they can be singled out as influenced by the sort of settings Oswald would have encountered during his work on the contrafacta. These more ambitious compositions (both employ hoquetus effects) betray a mixed style in which elements of contemporary discantus rules are introduced to such a degree that a more precise use of the mensural notation was required. I would not be surprised if one of them (Kl 93) might eventually turn out to be another contrafactum, possibly based on an Italian model. The notational difficulties with the other, the surprisingly short Kl 94, apparently caused the scribe of WolkB[16] to abandon the copying process, leaving the discantus staff empty. The inaccuracies in the notation of this song in WolkA, of both pitch and rhythm, make a reconstruction of the intended counterpoint very difficult. However, the fact that the initial melisma of Kl 94 is identical to the initial melisma of Oswald’s monophonic song Kl 13 (Wer ist, die da durchleuchtet) is an indicator for his authorship of both compositions. It is also a further confirmation of the open borders between monophony and polyphony in these repertories.[17] The remaining two songs (Kl 68 and Kl 101) appear to be a mixture of the above-mentioned styles, featuring elements of non-mensural polyphony as well as a more standard use of the contemporary discantus rules, particularly for the cadences. In fact, most of the songs in Table I mix these elements to a certain degree – some more so, some less – and it appears that Oswald, who may have been learned in the tradition and practices of non-mensural polyphony but who was probably not trained in the techniques of the discantus treatises, tried to apply to his own compositions some of the features of these treatises, which he would have come to know through his contrafacta. Both songs also show modal ambiguity in the surviving sources: Kl 68 is notated once in a C-mode (WolkA) and once in a D-mode (WolkB), the latter in a monophonic version, while Kl 101 – the only song from Oswald’s non-mensural polyphony with concordances outside his own manuscripts – comes in a whole variety of modes.[18] The transmissions of Kl 101 display a large range of features, which link the song to monophonic and non-mensural practices. These include shifting modality, non-rhythmical notation for the tenor vs. a mensurally notated discantus, hints at a reference rhythm, the use of stroke notation, and wrong clefs for the discantus in both Wolkenstein codices. Furthermore, its tenor melody was consequently adapted in the Lochamer Liederbuch to comply with a more contemporary approach to discanting and intabulation, complete with a clear rhythmic ordination, an initial melisma, and the rubric “tenor”.

Transcribing and reconstructing Oswald’s polyphonic songs

A note-against-note transcription is largely unproblematic for those songs which coordinate the two voices by simply counting the notes, such as Kl 51 and Kl 84, or even the melodically erratic Kl 37/38. However, those transmissions with a substantial amount of red notation and occasional bursts of diminutions do not only complicate an edition but also put significant obstacles in the way of reconstructing an intended performance practice. Previous editors have sought a definite rhythmical solution for these pieces and in doing so created versions which, instead of doing justice to the central non-mensural aspects of this repertory, went in the opposite direction by offering pointedly rhythmical editions to the extent of proposing irregular dance metres. I would suggest a new approach to the edition of these pieces, which leaves open certain aspects of their rhythm, and to add a commentary in which the rhythmic openness and fluidity required for a successful performance is discussed: a performance that is directed by the flow of the text and the modality of the melody rather than a prescribing mensural notation. An attempt in this direction can be seen in my edition of Kl 75 (» Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an).[19] For this song the scribe apparently used mensural note signs to show degrees of rhythmic fluidity in a melodic line: while black semibreves and minims represent the slow and fast ends of this spectrum, red semibreves take the middle ground. The orthodox meaning of red semibreves as a sesquialtera proportion in a major prolation is here used in an unorthodox way to indicate a minute rhythmic shift – usually an acceleration – instead of a precise rhythm.[20] This would also explain why in songs like Kl 75 red semibreves tend to occur in both voices simultaneously and in parallels.

Edition of Kl 75, Oswald von Wolkenstein, Wol auff, wol an (A-Wn Cod. 2777, fol. 35r). Black semibreves are represented as black note heads, black minims as quavers, and red semibreves as hollow (white) note heads; an online scan of the original notation can be found under the link http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10048508.

The parallels, in turn, belong to the practice of fifthing. In Oswald’s songs, however, they do not only appear as parallel fifths, but also as parallel sixths with apparent equivalent meaning. It seems that Oswald had extended the concept of fifthing to include the interval of the sixth and employed both interchangeably. This equivalent use can be observed in Kl 51, Kl 75,[21] Kl 77, Kl 79 and Kl 84.

The notational intricacies that surround many of these pieces (especially the unorthodox use of red notation) as well as inaccuracies and mistakes regarding pitch and rhythm together with the lack of a control group of similar compositions posed a major obstacle for their edition and interpretation, so that – lacking an adequate edition and a proper ‘tool kit’ to deal with their specific features – these pieces were rarely performed or recorded in the modern age. Four songs make an exception: Kl 51, Kl 84, Kl 93, and Kl 101 actually have become some of the most popular Oswald songs today, mediated through early reference recordings of the early music revival.

Non-mensural polyphony by the Monk

Of the eight polyphonic songs in the surviving œuvre attributed to the Monk of Salzburg, the following list excludes only W 31 (Jv, ich iag nacht vnd tag), a contrafact canon on a French chace (Umblemens vos pri merchi) which is reminiscent of Oswald’s contrafact process, and the canon W 55* (Ain radel: Martein, lieber here). The following categorisation (see Table II) includes valuable observations shared by Christoph März in his edition and commentary of the Monk’s secular songs.[22] Nearly all the songs (W 1-W 5) stand together as a block in the main manuscript and in the order of their editorial numbers. While most of the sacred songs in that manuscript have titles, these five and the immediately following three monophonic songs G 42[23], W 7[24] and W 8[25] are (almost) the only secular songs with titles and substantial rubrics. The latter include the rubric ‘tenor’, which despite their monophonic notation associates them with polyphony.[26] One could argue that they belong to the set of polyphonic pieces but that their second voices did not need to be notated, whereas most of those pieces with two notated voices require polyphony to some degree: either for textual reasons in the motet-like songs or for the sound effect in the horn-like songs.[27] (See Table II.)

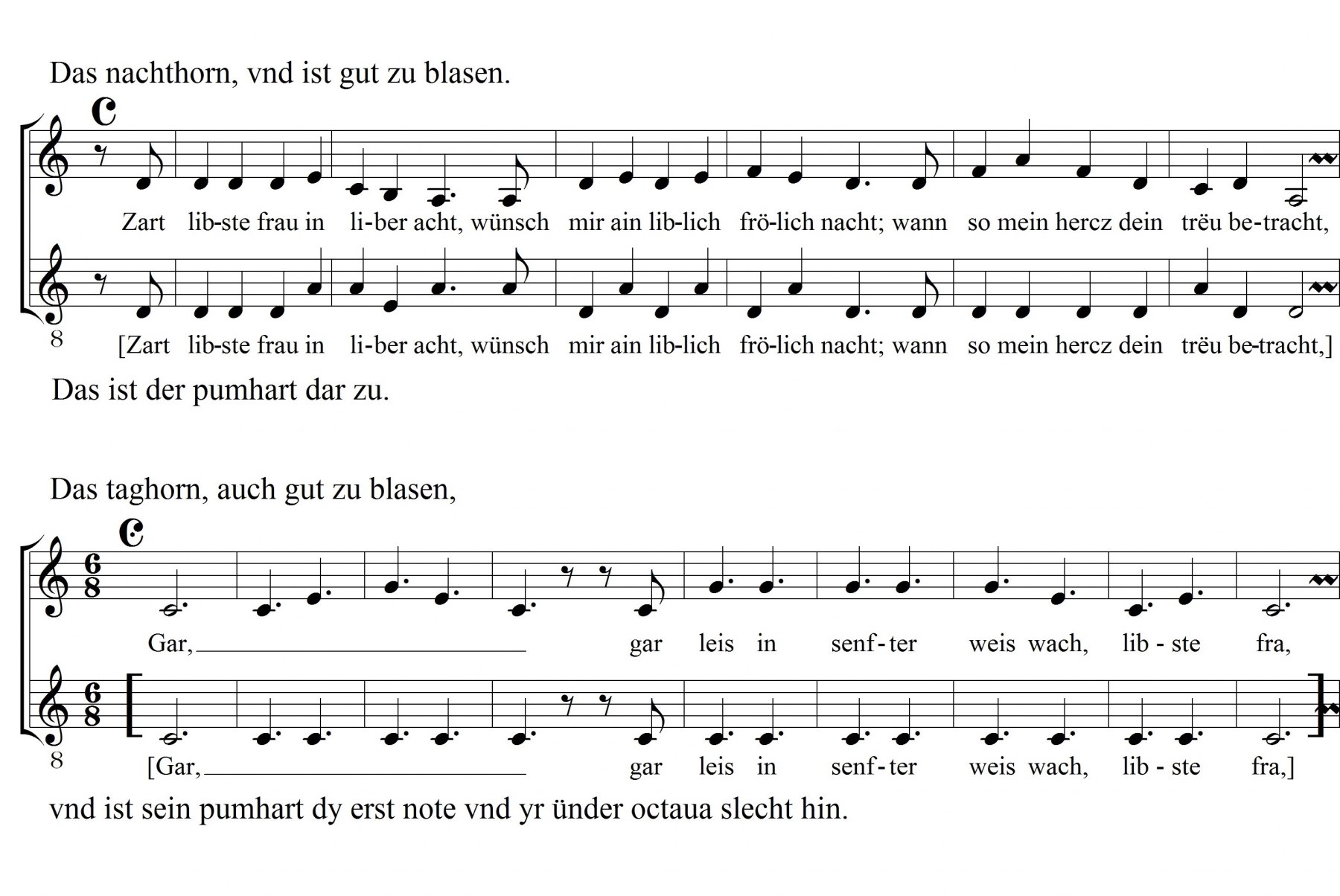

W 1 Das nachthorn: Zart libste frau in liber acht

- D, fols 185v–186r,[28] 2vv: mensural with mensural sign (imperfectum minor) and implied structural use; D-mode (C2 clef)

- D, fols 245v–246r, 1v: semi-mensural with stroke notation and reference rhythm; G-mode (with one b-flat)

- K, fol. 658r–v, 1v: chant notation; F-mode

W 2 Das taghorn: Gar leis in senfter weis wach, libste fra

- D, fols. 186v–187r),[29][RS6] [ML7] 2vv: mensural with mensural sign (imperfectum major); C-mode (C1-clef)

- He, fol. 316r (text); fols. 315r–316r (melody), 1v: stroke notation; C-mode

- K, fols 657v–658r, 1v: chant notation; F-mode

- St, fol. 7v (text); fol. 43v (beginning of the melody to the text of W 5), 1v: stroke notation; D-mode

- Wn, fols 64v–65r, 2vv: mensural; melody serves as tenor line of a new motet, Veni rerum conditor; C-mode (notated a third too high)[30]

W 3 Das kchühorn: Untarnslaf tut den sumer wol, ‘organal’ (unisono)

- D, fol. 187r–v,[31] 2vv?: mensural with triple-metre reference rhythm; C-mode

- D, fols 198v–199v, 1v?: mensural with duple-metre reference rhythm; C-mode

W 4 Ain enpfahen: Wolkum, mein libstes ain

- D, fols 187v–188r, 2vv: mensural notation, occasional reference rhythm; D-mode

- Sb, fols 49v–50r, 2vv: notation lost except for incipit with mensural notation and reference rhythm; D-mode

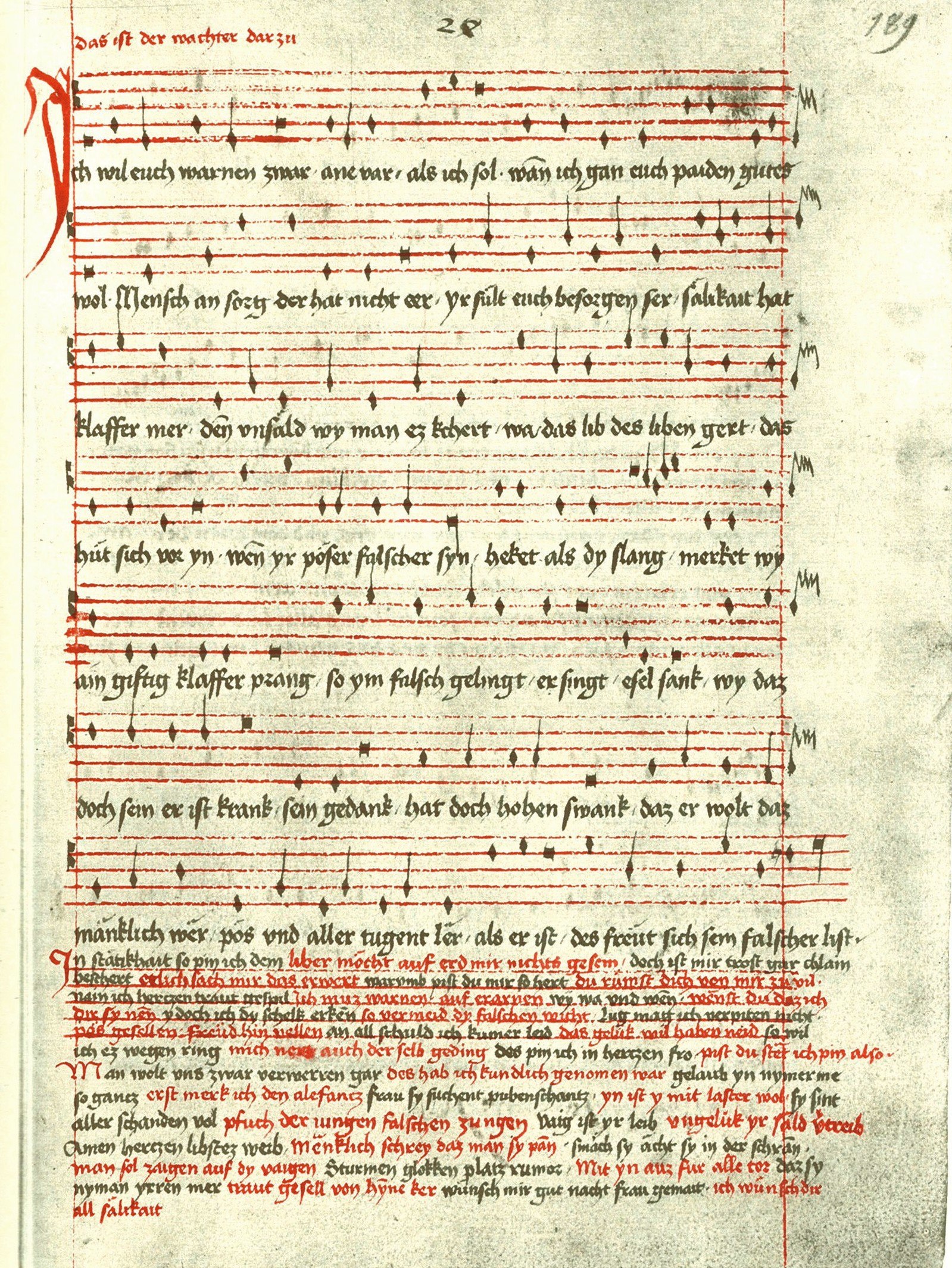

W 5 Dy trumpet: Hör, libste frau, mich deinen knecht

- D, fols. 188v–189r,[32] 2vv: mensural with occasional reference rhythm; D-mode

- Sb, fol. 26v, fols 34v–35v), 1v?: notation lost except for discantus incipit with mensural notation and occasional reference rhythm; D-mode

- St, fols. 43v–44r (beginning of the melody of W 2), 1v: chant notation with indication of stroke notation; D-mode

W 54* Von sand Marteins frewden: Wolauf, lieben gesellen vnuerczeit

- E, fols 168r–170v, 2vv: semi-mensural and stroke notation; E-mode

- Wi, fols 1v–2v, 2vv: mensural with occasional reference rhythm; E-mode

- A, fols 180r–182r, 2vv: semi-mensural; E-mode

- A, fol. 183r, 2vv: semi-mensural; E-mode

- Sb, fols 112v–113r, 2vv: notation lost except for tenor incipit with mensural notation; E-mode

- Se, fol. 2r, 2vv (only tenor incipit notated): semi-mensural; mode unclear (no clef).

Table II: Polyphonic songs by the Monk of Salzburg: an annotated list.

Key to manuscript sources

A D-Mbs Cgm 715D A-Wn Cod. 2856, Mondsee-Wiener LiederhandschriftE A-Wn Cod. 4696, Lambacher LiederhandschriftHe V-CVbav cpl. 1260K D-Mbs Cgm 4997, Kolmarer LiederhandschriftSb F-Sm 222 C. 22, Strasbourg Codex, lost to fire in 1870Se D-B Ms. germ. fol. 1035St I-VIP o. Sign. Sterzing (Vipiteno), Sterzinger MiszellaneenhandschriftWi D-WH Ms. 118, Windsheimer FragmentWn D-Mbs Clm 14274, St Emmeram Codex.This shortlist of non-mensural polyphony by the Monk of Salzburg can be further organised according to different characteristics, allowing some of the songs to tick several boxes. A first subdivision includes those which in their titles as well as their melodic construction evoke melodies or signals of wind instruments: W 1, W 2, W 3 and W 5. The melodies are made up of intervals that can be associated with the scale of natural overtones. As März has pointed out, the melodies are meant to be a vocal imitation of the sound of a horn or a trumpet and were not written for such an instrument, as they include notes that cannot be played by using harmonic partials only. That three of the rubrics actually suggest a performance on wind instruments (‘gut zu blasen’) could be an extended reference or a misunderstanding by a later scribe, who based the assessment on the titles of the melodies.[33]

Trumpet and horn-signal songs

The imitation of horn or trumpet signals in vocal music was well established by the late fourteenth century and is not unique to the Monk of Salzburg. It can, for instance, be found in other contemporary repertories such as the Ars nova chace and the Trecento caccia.[34] However, a distinction should be made between the three songs with horn imagery in the title (W 1, W 2, W 3) and the ‘trumpet’ (W 5). While the melodic profile of the ‘trumpet’—even with its tendency towards more and wider leaps—does not appear to deviate significantly, its rhythmical structure is much more pronounced, obviously imitating trumpet signals. The melodies of the ‘night horn’ (W 1), the ‘day horn’ (W 2), and the ‘cow horn’ (W 3), on the other hand, move much slower and smoother by comparison, maybe imitating typical call signs of horn instruments. Reinhard Strohm has proposed a new interpretation for the names of the first two melodies: the soundscape of late medieval Austrian cities included the so-called ‘Hornwerke’, usually simply referred to as ‘Horn’ in contemporary sources (» Kap. Hornwerke). These were organ-like instruments installed on church towers or fortifications; when activated by the means of bellows, they emitted a far-carrying sound. One ‘Hornwerk’ that was installed at the Salzburg castle in 1515 played a multiplex F major chord – whether also a melody is not known.[35] The one installed at St Stephen’s church in Vienna in 1456 was once referred to as ‘Taghorn’. It seems that the signals were maintained and used by the secular authorities to announce specific times of the day, which included the announcement of certain laws, such as curfews. The three horn-like melodies by the Monk might, therefore, reference these ‘Hornwerke’ and their associated functions in daily city life rather than actual horn signals. This reference might also explain why they were notated with second voices, enhancing their sound possibly to better imitate the effect of a ‘Hornwerk’.

The horn-like songs have something else in common: Two of them (W 1, W 2) have a second voice called ‘pumhart’ (‘bombarde’ or bass shawm) in the accompanying rubric and feature unique C1 and C2 clefs for their texted voices. This transposes them into the discantus range, while their second voices, the ‘pumharts’, occupy the lower tenor range. Both ‘pumharts’ have a drone-like appearance and the ‘pumhart’ for W 2 is not even notated, but only described in the rubric as the first note of the song down an octave (c). However, what at first sight might seem nothing more than the description of a continuous drone that could be applied to a plenitude of melodies, turns out to be carefully planned. The melody employs only the notes c‘, e‘, g‘, a‘, and c” (with one passing minim f‘) in the entire melody, thus creating a completely consonant contrapunctus simplex with the described ‘pumhart’ on c. In practice, the ‘pumhart’ note would probably have been repeated with each note of the cantus to accommodate the entire text, just as in the notated ‘pumhart’ of W 1.[36] The name for these accompanying voices was probably derived from their low range and at the same time extended the metaphor of a wind instrument. It does not seem to imply an intended instrumentation. All concordances to these two songs are monophonic, notated down a fourth, fifth, or octave (that is, in the normal tenor range), and transmit the melodies without their ‘pumharts’. See » Notenbsp. Das Nachthorn & Das Taghorn.

Das Kchuhorn (W 3)

With some caution, the next song in the manuscript, W 3, could be argued to fall into the same category as W 1 and W 2. Its intended form and polyphonic structure are not at all clear from the manuscript layout. Since it is grouped with the polyphonic pieces and has a comparable form to the motet-like W 5,[37] März plausibly suggested a heterophonic structure: both voices of the song have the same basic melody with the ‘tenor’ in slower note values, while the ‘discantus’ has a diminuted version.[38] Sung together the two melodies result in a motet-like heterophonic structure that perfectly matches the low stylistic level of the text: where in W 5 the composition re-enacts a classic medieval aubade, W 3 transfers the setting from dawn to a lunch-time nap and from the courtly chamber to the stables. (» Hörbsp. Untarnslaf - Das kchúhorn.) The music does the same, compressing a more artistic, polyphonic setting, such as W 5, into the bucolic realm of the peasants, who have to make do with a ‘monophonic motet’. In my interpretation of this song, I went a step further and, following the lead of the notations for W 1 and W 2, transposed the ‘discantus’ up an octave to further differentiate the voices and their functions, thus transforming the ‘tenor’ into a ‘pumhart’.[39] The process of adding a lower voice to the main melody in the three horn-like pieces needs to be distinguished from the practices of fifthing and discanting, in which the new counterpoint is added above the main melody. The Monk’s ‘pumharts’ could be compared to some of those songs by Oswald (see the group of pieces marked with (+): Kl 84, Kl 51 and Kl 91, above), where it is difficult to discern the cantus prius factus and where drone-like passages occur in the lower voice. These could indeed be cases of ‘pumharting’, where the added voice is the tenor.

Motet-like songs of the Monk

Another possible subdivision within the Monk’s non-mensural polyphony is the group of motet-like songs: W 3, W 4, W 5, and W 54*. All of them have two texts and therefore appear to require polyphony to function. Yet, as stated above and as the following list attests, the sources even transmit monophonic versions for some of these pieces. All of them have both voices in the same range including multiple voice crossings and all of them appear to stage a dialogue, with some of the voice parts specifically marked. In W 4, the two voices, even though they are in the same range, represent a female and a male speaker and are marked as “sy” (her) and “er” (him) respectively. In W 5, half the first voice is written with red notation and red text, which in this case does not refer to rhythmic differentiation but signifies the speaker: “Das swarcz is er, das rot ist sy” (The black [notation and text] is him, the red [notation and text] is her). The rubric to the second voice informs about the third party: “Das ist der wachter dar zu” (This is the watchman for this). » Abb. Dy trumpet: Hör, libste frau.

Abb. Dy trumpet: Hör, libste frau, Mönch von Salzburg (2 Abbildungen)

Der Mönch von Salzburg, Lied W 5, in der Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift“, » A-Wn, Cod. 2856. © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.Weltliches Liebeslied (Taglied, Aubade) als Dialog von zwei Stimmen mit Tenor: „Das schwarz ist er, das rot ist sie“ (fol. 188v); „Das ist der wachter dazu“ (fol. 189r).Er: Hör, liebste Frau, mich, deinen Knecht! Sie: Was bedeutet des Nachts der viele Lärm? Wächter: Ich will euch nur warnen, ohne Gefahr…Aspects of counterpoint and modality in the Monk’s polyphonic songs

Though the polyphonic songs in the Monk’s main manuscript are clearly notated mensurally—even including the occasional mensural sign, a feature absent from the Wolkenstein codices—their use of mensural notation betrays elements of a non-mensural or semi-mensural practice: W 1 and W 2 appear to employ the above quoted structural use of mensural notes with minimas reserved for upbeats, semibreves for almost the entire melody, and dotted semibreves and breves for cadence notes.[40] W 4 and W 5, on the other hand, both make abundant use of the semi-mensural practice of the reference rhythm.

In contrast to Oswald, who introduces elements from discantus practices to his non-mensural polyphony, the Monk uses almost entirely consonant note-against-note techniques, and whereas contrary motion and fifthing make up most of his counterpoint, he has hardly any cadences in contrary stepwise motion. Particularly the horn- and trumpet-like melodies W 1, W 2, W 3 and W 5, which largely consist of melodic leaps (including cadences), prevent such progressions. Even the anonymous motet Veni rerum conditor in the St Emmeram Codex (» D-Mbs Clm 14274), a later composition using the melody of W 2 as tenor, appears to be little more than a written-down piece of non-mensural polyphony, though with fewer parallels.[41]

Modal ambiguity, a typical sign of monophonic music, is also present in the transmission of the Monk’s non-mensural polyphony, though not to the same degree as in Oswald’s repertory. The only melody with a clear modal shift is the D-mode song W 1, which in the Kolmarer Liederhandschrift (K) appears monophonically and in an F mode. The unclear modality of W 2 (normally in a C- or F-mode) in the Sterzing manuscript (St) could be attributed to its confusion with W 5, which is in D. Whether the result of a confusion or a conscious quotation, the degree of intertextuality in these two narrow repertories of the Monk and Oswald with monophonic genres strengthens the link between monophonic and polyphonic œuvres and opens up the monophonic repertories to an almost unlimited application of the practices of non-mensural polyphony.

Anmerkung B.4c

Revised version of Marc Lewon‚“Übersingen“ und „Quintieren“: Non-Mensural Polyphony in Secular Repertories: Oswald von Wolkenstein and the Monk of Salzburg, in Tess Knighton and David Skinner (Hrsg.), Music and Instruments of the Middle Ages. Essays in Honour of Christopher Page (Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music 22), Woodbridge: Boydell, 2020, 385-403.

[1] On these sacred repertories, see » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Grundlagen (Alexander Rausch), and » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Arten und Kontexte (Reinhard Strohm).

[2] Pelnar 1978, and substantiated in Pelnar 1982, Textband.

[4] „WolkA“: A-Wn Cod. 2777 (?Vienna, c. 1425): „WolkB“: A-Iu o. Sign.

[5] See Lewon 2017, pp. 134–137.

[6] This assessment supports Pelnar’s statement (Pelnar 1982, Textband, p. 21) against a development from a more ‘primitive’ to a more ‘sophisticated’ counterpoint within Oswald’s œuvre: ‘Auf keinen Fall dürfen die Gruppen [‘bodenständig’ und ‘westlich’] chronologisch als Entwicklungsphasen aufgefaßt werden, wie es etwa Salmen bei seiner Datierung der Lieder macht’ (Under no circumstances should the categories [‘native’ and ‘Western’] be understood as chronological phases of a development, as Salmen did in his dating of the songs).

[7] Pelnar 1978, p. 275f.

[8] For a more comprehensive summary of the concept of ‘reference rhythm’, see Lewon 2012, 169–173.

[9] ‘Strichnotation’: see » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs and Glossary.

[10] The main manuscript for the songs of the Monk of Salzburg, the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift (A-Wn Cod. 2856), is one of the first musical manuscripts that makes a clear division between secular and sacred songs with the rubrics “werltlich” and “geistlich”; see März 1999, pp. 367–368.

[11] ‘Kl’ numbers refer to the numeration in the standard text edition, Klein 2015 (and earlier).

[12] ‘W’ (‘weltlich’) numbers refer to the numeration in März 1999.

[13] The rubric to W 8 (Ich klag dir, traut gesell) by the Monk confirms this practice ex negativo: “Ain tenor von hübscher melodey als sy ez gern gemacht haben darauf nicht yeglicher kund übersingen” (A tenor with a pretty melody, the way they liked to make them. Not everyone was capable of singing an upper voice to this). See also » B. Kap. Ich klag dir traut gesell (David Murray).

[14] Lewon 2011; see the table on pp. 189-191. Not all of the remaining songs listed there are proven contrafacta, but their notation and counterpoint strongly suggest a model from contemporary polyphonic exemplars. There is one more piece that could be added to the list of twelve below: Kl 21 (Ir alten weib), a monophonic song that appears to be a cognate to the Neidhart song Der sawer kübell - Niemand sol sein trauren tragen lange (see Mark Lewon, ‘Oswald quoting Neidhart: Ir alten weib (Kl 21) & Der sawer kübell (wl)’ (2014), accessible online at: https://mlewon.wordpress.com/2014/06/30/oswald-quoting-neidhart/). Michael Shields (2011) has suggested that the third section of this Oswald song could contain a piece of hidden polyphony in the form of a fuga. Should this prove true, then Kl 21 could be another case of non-mensural polyphony, employing reference rhythm. Since the claim is hard to substantiate and canons are excluded from the list – most of them being contrafacta – I will, for the time being, leave this song aside.

[15] In WolkA, only Kl 79 was notated separately a few pages later, probably because it was added with a second layer of repertory. For the scribal layers of the manuscript, see Delbono 1977. In WolkB, song Kl 37/38 was separated from the block and notated in a monophonic version in the first half of the manuscript, while the other four were grouped together.

[16] A-Iu o. Sign. (?Basel, c. 1432).

[17] See chapter 5.3 ‘Oswald quoting Oswald: Crossing the Border to Polyphony’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 260–268.

[18] For an in-depth analysis of the modal shifts of Kl 101 in the different sources, see chapter 5.1 ‘“Wach auff, mein hort”: A Melody of Modal Ambiguity’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 241–53.

[19] A recording of this edition, though experimentally transposed to a D-mode, can be found on the album The Cosmopolitan – Songs by Oswald von Wolkenstein. Ensemble Leones (Christophorus, 2014), track 9. Other examples for a new edition of Oswald’s non-mensural polyphony can be found in Lewon 2016a, ‘Ach senliches leiden (Kl 51)’, pp. 35–37, and ‘Des himels trone (Kl 37)’, pp. 38–43.

[20] For a first proposal of this interpretation, see Lewon 2011, pp. 168–191 at pp. 182–184.

[21] In » Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an, most melismas are in parallel fifths; the cadential melisma over the word ‘springen’ and a section of the final melisma of the clos, however, run in parallel sixths.

[22] März 1999. See also » B. The secular songs of the Monk of Salzburg (David Murray). The secular songs (‘W’ for weltlich), are edited in März 1999, the sacred songs (‘G‘ for geistlich), in Waechter-Spechtler 2004.

[23] Rubric: “Der tenor ist der tischsegen” (This tenor is [called] the benediction).

[24] Rubric: “Der tenor haizt der freüdensal nach ainem Lusthaws pey Salzburg […]” (This tenor is called the house of pleasure after a hunting lodge near Salzburg […]).

[25] Rubric: see n. 13 above.

[26] For a more formal definition of monophonic ‘tenores’, see März 1999, pp. 11–2, 14–19, 31–3 and 36–40. An extended interpretation of the use and function of such ‘tenores’ by Reinhard Strohm and myself is given in Lewon 2018, pp. 225–226.

[27] In fact, Lorenz Welker argued that the motet-like song W54* is an example of extemporised counterpoint, which needed to be written because it carries a text. In other circumstances the discantus would not have been notated, but extemporised: see Welker 1984/1985, p. 55.

[28] Melody rubric: “Das nachthorn, vnd ist gut zu blasen” (The night horn, and it is suitable for wind instruments); second voice rubric: “Das ist der pumhart dar zu” (This is the accompanying bombarde).

[29] Melody rubric: “Das taghorn, auch gut zu blasen, vnd ist sein pumhart dy erst note vnd yr ünder octaua slecht hin.” (The day horn, also suitable for wind instruments, and its bombarde is simply the first note down an octave).

[30] See Welker 1984/1985.

[31] Rubric: “Das kchühorn […]” (The cow horn […]).

[32] Melody rubric: “Das haizt dy trumpet vnd ist auch gut zu blasen. Das swarcz is er, das rot ist sy” (This is called the trumpet and it is also suitable for wind instruments. The black [notation and text] is him, the red [notation and text] is her). Second voice rubric: ‘Das ist der wachter dar zu’ (This is the watchman for this).

[33] See März 1999, p. 368.

[34] On the musical types trumpetum and tuba (‘trompetta music’), see Strohm 1993, pp. 108-111 and passim.

[35] See » E. Kap. Hornwerke, where it is now suggested that a Hornwerk may have existed in the 15th century on the tower of the Salzburg parish church or of the town hall.

[36] März 1999, pp. 12 and 368.

[37] Both of them feature a dialogue of two lovers in their main melody, accompanied by a running commentary in the second voice.

[38] März 1999, p. 375.

[39] A recording is » Hörbsp. Untarnslaf - Das kchúhorn (Ensemble Leones), https://musical-life.net/audio/untarnslaf-das-kchuhorn (2015), where I refer to this song as a ‘pseudo-’ or ‘peasant-motet’.

[40] A stylised semiminima is used as the custos throughout the section with polyphonic songs and monophonic ‘tenores’.

[41] See Welker 1984/1985.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Marc Lewon: „Non-mensural polyphony in secular repertories: Oswald von Wolkenstein and the Monk of Salzburg“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich, <https://musical-life.net/essays/non-mensural-polyphony-secular-repertories-oswald-von-wolkenstein-and-monk-salzburg> (2020).